What if we build it and leave the door open? Will everybody come inside?

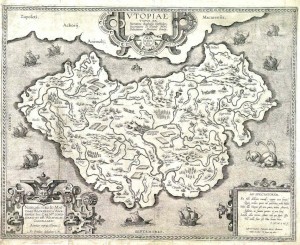

That’s the gambit of Stephen Duncombe’s new site, The Open Utopia, and somewhat also a motto for these first few weeks of my current grad class. Last week’s question was, what does Utopia have to do with globalization? The class is built around three imaginary places — Utopia, Faerie Land, and Paradise — and we aim to mash these literary archetypes up against the massive surge of information, maps, first-hand accounts, misrepresentations, propaganda, and assorted other fictions that maritime voyages brough back to Europe in the early modern period. Reading assorted bits from Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations (1598-1600) alongside More, Spenser, Milton, Shakespeare, and others helps recall that geography always appears alongside and entangled with fantasy.

1. Globalization needs utopia, especially in our catastrophe-driven era, because we need to remember our duty to futurity. Not just in a hope-and-change progressive way, but as a pressure, force, and burdon. It’s there, waiting for us, and we can’t not travel forward, even though it’s not an easy road. If it’s a direction, it’s also a fantasy about a wiser past or less brutal future.

2. Ecologically speaking, I’m struck on this reading by how much More emphasizes the relative dearth of natural resources in Utopia — little iron, relatively infertile soil, no gold or gems (which the Utopians despise anyway). Is the beautiful place / no place also already depleted? Human capital, used and shared, makes up for this lack, but as we contemplate the scarcity of natural resources in the 21c and impending struggles over arable land, fresh water, oil, and other commodities, perhaps we can find in More a way to think about adaptation?

2. Ecologically speaking, I’m struck on this reading by how much More emphasizes the relative dearth of natural resources in Utopia — little iron, relatively infertile soil, no gold or gems (which the Utopians despise anyway). Is the beautiful place / no place also already depleted? Human capital, used and shared, makes up for this lack, but as we contemplate the scarcity of natural resources in the 21c and impending struggles over arable land, fresh water, oil, and other commodities, perhaps we can find in More a way to think about adaptation?

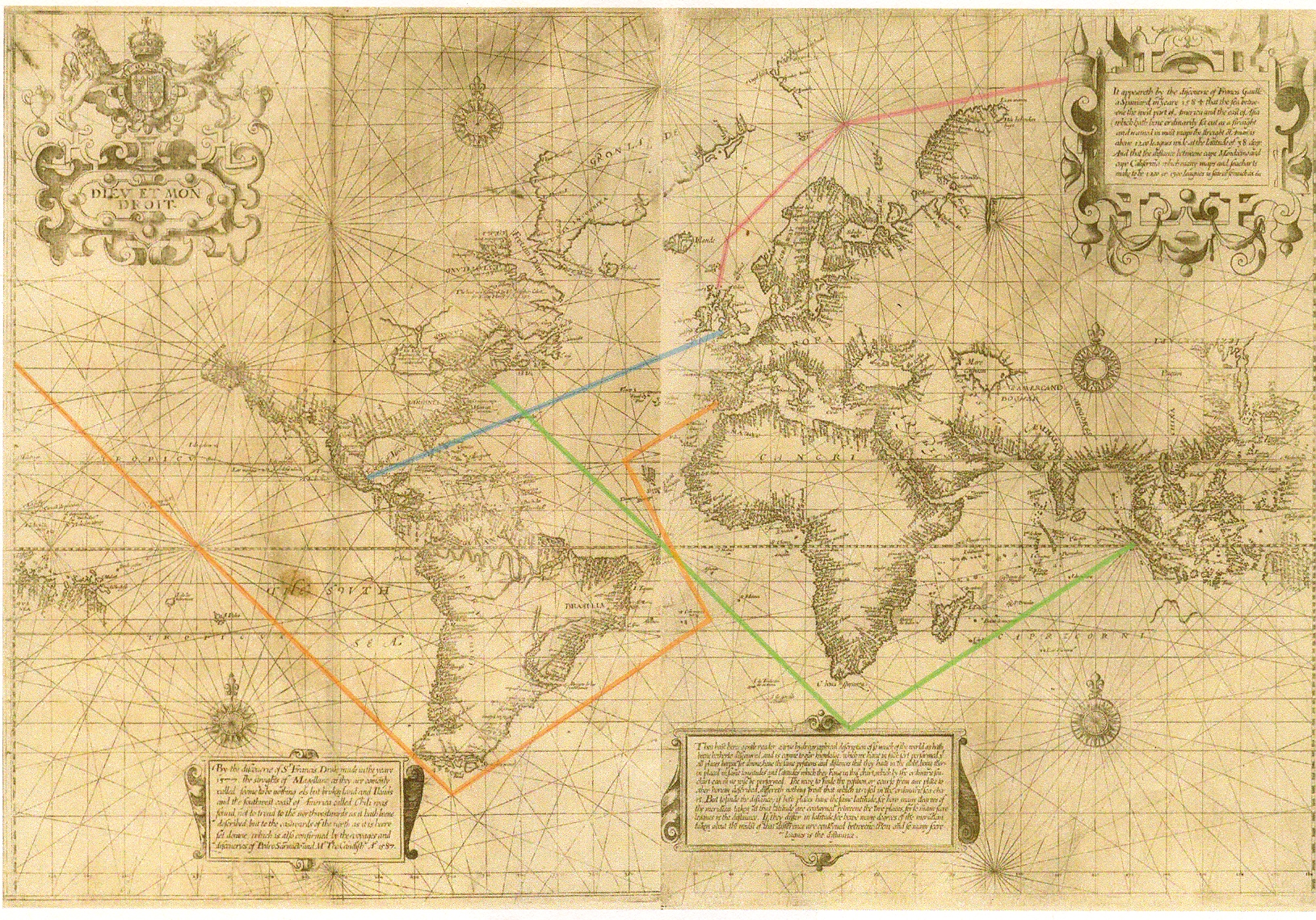

I’m also enjoying the prospect of Richard Hakluyt, a later-generation humanist clergyman, engaging in dialogue with More’s Utopian table talk. From humanist skepticism to expansionist boosterism, in just a few generations!

Here’s Hakluyt, on how he came to write his book of maritime histories:

…it was my hap to visit the chamber of Mr. Richard Hakluyt my cousin, a gentleman of the Middle Temple, well known unto you, at a time when I found lying open upon his board certain books of Cosmography, with a Universal Map: he seeing me somewhat curious in the view thereof, began to instruct my ignorance, by showing me the division of the earth unto three parts after the old account: he pointed with his wand to all the known seas, gulfs, bays, straits, capes, rivers, empires, kingdoms, dukedoms and territories of each part, with declaration also of their special commodities, and particular wants, which by the benefit of traffic, and the intercourse of merchants, are plentifully supplied (Epistle Dedicatory to the first ed. 1589).