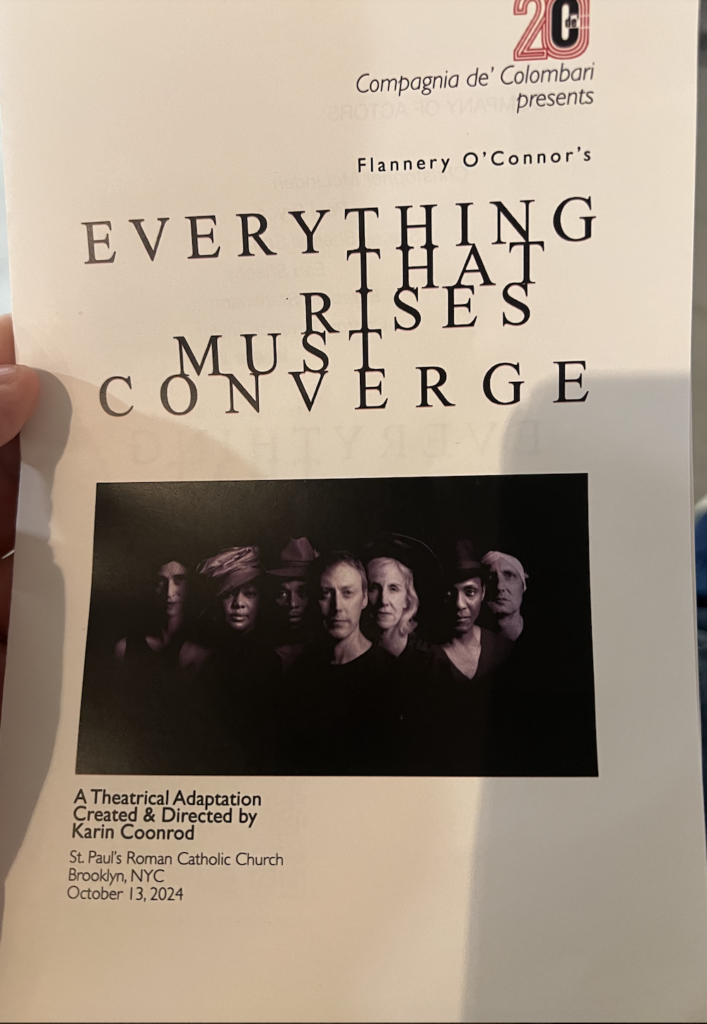

As I gear up to host Karin Coonrod and the Compagnia de’ Colombari at St. John’s for Whitman on Walls! in less than two weeks, I made a quick run down to Cobble Hill on Sunday 10/13 to see the last performance of the company’s staging of the Flannery O’Connor story “Everything That Rises Must Converge” at St. Paul’s Church. As with the other Colombari productions I’ve seen – The Tempest at LaMaMa, Merchant of Venice at the Yale Law School, King Lear last summer – the signature force of the staging comes in a sometimes overwhelming dramatic intensity. In this production, especially, the undersong was a bitter and in some ways complicit comedy – we laugh because we recognize human hypocrisy, and because laughing hides our deeper and uncomfortable connections.

Coonrod writes in the Director’s Note that she, like me, first read O’Connor in a college lit class. She’s been developing theatrical versions of a few of the stories since the first days of Colombari, twenty years ago at the University of Iowa. Conrood calls O’Conner “the American Dante,” and emphasizes the writer’s staying power as we approach the centenary of her birth in 2025.

“Everything That Rises,” the title story of O’Connor’s second (and final) collection of short stories, published posthumously in 1965, narrates a series of encounters on a city bus, in which Julian, a frustrated recent college graduate and aspiring writer, is embarrassed by the racist attitudes and behavior of his mother. The comic byplay between Julian, his mother, and the other riders of the bus, including a Black woman and her child as well as a tall Black man in a suit reading a newspaper, skewers both Julian’s progressive pretensions and his mother’s once-genteel patronizing. When his mother attempts to give the boy a shiny penny and gets slapped by the boy’s irate mother – the two mothers wear the same garish purple hat, in case we miss their symbolic connection as mothers raising sons in a dangerous and changing world – Julian’s mother falls down by the side of the road, presumably having a stroke and certainly retreating into the past that she has long since lost.

The final lines of O’Connor’s story draw Julian back toward his suffering, perhaps dying, mother, despite his revulsion at her racism and blindness to the world. He calls her “Darling, sweetheart” and “Mamma, Mamma!” but fails to catch her attention. At the story’s end, O’Conner brings the two into uneasy communion through failure: “The tide of darkness seemed to sweep him back to her, postponing from moment to moment his entry into the world of guilt and sorrow.”

Like Dante, O’Connor treats the spiritual as more material than the world of physical reality. The title’s imperative – “must converge!” – refers on some level to the social project of racial integration in the American South, which Julian’s mother fears and rejects. “They should rise,” she says, “but on their own side of the fence.” But the “everything that rises” that matters for O’Connor is less about the physical integration of the bus, or Julian’s social and professional prospects, than it is a religious maxim, an inescapable truth. The word “must,” as I read O’Connor’s title, entrains all of us into a human “world of guilt and sorrow.” To rise in this world does not mean to achieve success but to recognize suffering.

Colombari’s staging, which scrupulously followed the requirements of the O’Connor estate in speaking every word of the story, including every the “he said” and “she said,” emphasized the bitter comedy of the mother’s efforts to engage the young boy on the bus, and also Julian’s failure to communicate with the Black businessman. The kicker in O’Connor’s stories, as in Shakespeare’s tragedies, tends to be brutal. As with Colombari’s King Lear this past June, I found something gloriously human in this show’s presentation of hypocrisy, jealousy, small acts of empathy, and an overflowing of pain.

The films Colombari will present of “Song of Myself” won’t hit all these tragic notes. But I am looking forward to something like the same intensity on the St. John’s campus in less than two weeks.