Are you answer’d? (4.1.61)

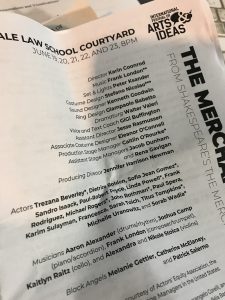

At the rousing close of the Compagnia di Colombari’s moving production of Merchant, originally staged in the Venice ghetto in 2016 and reprised this week in the courtyard of Yale Law School, the five actors who played Shylock in his five different scenes stood together and confronted the audience. They presented distinctive faces: an Indian man who also played Gratziano (1.3), an Uraguayan man who also played Aragon (2.5), an American woman cross-cast as the Duke (3.1), an African-American man who played a compelling Morocco (3.3), and an American man who doubled as Tubal (4.1). They reprised Shylock’s speech from the trial insisting that he need not explain his refusal to show mercy to the Christians who had mocked him, stolen his daughter and his ducats, and spurned his offers of professional friendship. “I’ll not answer that,” he/they intoned. “But say, it is my humor.” The acting collective stood for the Jewish identity that Shylock embodied both within the play and in the past four centuries of Western cultural history — but the speech they collectively spoke asserted, with Shakespearean doubleness, an individual’s refusal to submerge his particular selfhood in service to an ethically compromised public good.

The play and this production partly admire Shylock for his desire to stand for himself, “as if,” to quote another Shakespearean anti-hero, “a man were author of himself.” But the play destroys him for his individuality, while making the audience complicit in that destruction.

Linda Powell as Portia (Arts & Ideas)

I sat in the on-stage seats in the courtyard last night, which meant that at the end of the trial scene, after Linda Powell’s commanding Portia-as-Balthazar pronounced forced conversion and financial ruin on Shylock, I was required to stand, drape the red sash of Christianity on my left shoulder, and clap and smile along with the full cast at the Jew’s solitary departure. I didn’t feel good about it — except that I like it when art gets under my skin.

The most emotionally wrenching moment of the night came the only previous time all five Shylocks appeared on stage together, when they discovered that his/their daughter Jessica had run off with pretty-boy Lorenzo, played with a you-can’t-touch-me smile by Paul Spera. The lines in which Shylock lamented the loss of his daughter and his ducats were parceled out to the Christians who surrounded, jeered at, and taunted the moneylender. (The winning side of the cast carried an oddly appropriate whiff of the scions of the American political elite: Linda Powell is Colin Powell’s daughter, and Paul Spera is the grandson of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg.) From the scrum of yellow-sashed Shylocks emerged Trezana Beverley’s female version of the role — Shylock as mother, in Coonrod’s phrase — to stun the courtyard with her keening cry. When she modulated later in the scene into “Hath not a Jew eyes,” she captured the night’s emotional core, as she would later reimagine the individual in the collective by playing the relatively small part of the Duke (4.1) as a figure of pathos and constrained power.

This production was deeply Shylock-centric, as you might expect when that part was quintuply cast. In an Ideas panel earlier in the week, I’d assembled a panel to think about “money-culture” in Merchant in which we consciously explored “Risk, Anxiety, and Generosity” through some of the less central figures, including Bassanio and the clown Launcelot Gobbo. Coonrod’s streamlined intermissionless production (I love Shakespeare without intermissions!) cut Bassanio’s arrow speech (1.1) and translated Launcelot into a commedia del’arte clown, played dazzlingly by Francesca Sara Toich, who performed in Italian a version of the speech about the fiend that my panel had discussed.

The focus on Shylock made it hard for the play’s romantic comedy to carry much balancing force. Flying the comic flag were a strong performance by Linda Powell as Portia and a lively opening bawdy dance number in Italian led by Loncilotto, adapted from an early 16c ballad on “amore.” “But who the devil,” asked the ballad, “would that devil be who wanted to speak of anything but love?” The play provided some disturbing alternatives.

Shylock did speak about love, and his lament on the loss of the ring his daughter spent in Genoa for a monkey highlighted his devotion to his deceased wife. “It was my turquoise,” he said to Tubal. “I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor; / I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys” (3.1) But the core of Shylock’s relationship with Venice and with the social and political worlds of the play flowed through money, debt, and exchange.

In the play’s crucial moments at trial, Shylock’s refused Portia’s offer/command/entreaty to submit to what she famously calls the “quality of mercy.” It might be that I (and some of my companions last night) were still under the spell of Tara Bradway’s wonderfully empathetic performance of that speech at our panel on Tuesday, but Linda Powell’s rendition of those familiar lines didn’t hit me in my gut. She seemed too clearly to know that Shylock would refuse; perhaps she was already thinking of her next move, the hyper-literalism in which she allowed him no blood to go along with his pound of flesh and thus broke him on a technicality.

Portia’s a tricky character, and much of our panel, not to mention its pre- and postgame discussion and my summer online class, has been trying to make sense of her. Does she represent feminist badassery, shrewdly negotiating a world of suitors who mainly want her money, not to mention the controlling hand of her dead father? Or does her behavior toward Morocco and Shylock display racism and inability to empathize beyond her elite circle? Some of our panelists have been batting around a theory in which Portia mirrors Ivanka Trump, another heiress whose beauty sometimes gets mistaken for a moral compass. In Coonrod’s production, Powell’s African-American identity counter-acted Portia’s textual whiteness and perhaps also subtly modified the figure’s relationship to Shylock. But the ethically unsettling feelings that emerged from the ring test (5.1) came through strongly in this production, especially as the five Shylocks took center stage for the closing moment.

In Venice in 2016, according to a review by Kent Cartwright in The Shakespeare Newsletter, the final tableau also highlighted Jessica and projected the word “mercy” in many languages onto the walls of the ghetto. In New Haven, Michelle Uranowitz, who played Jessica in both places, had injured herself during a nasty fall on Wednesday night, but I’m not sure if that’s why I didn’t see her closing move last night. Instead, we sat in the courtyard of one of America’s elite institutions of justice — Yale Law School grads currently comprise one-third of the United States Supreme Court — faced with five Shylocks pleading for inclusion and recognition. I want better answers for them, if not inside the play than in our increasingly unsettling history.

Update: Via Diana Henderson, whose front row seat had a better angle than my on stage seat, I’m told that the projection of “mercy” did happen at Yale, though in English only, rather than also in Hebrew and Italian in Venice.

Francesca Toich as Lancilotto (Arts & Ideas)

Are you answer’d?