We are thrilled to announce that the Blue Humanities Book Series, with Bloomsbury Publishing, is now accepting queries and proposals. Send us your watery books!

This project has been in the works for a while now, in collaboration with my amazing co-editor Serpil Oppermann of Cappadocia University and Ben Doyle from Bloomsbury. I think I first broached the topic with Ben at a particularly excellent craft brewery in Portland at ASLE in 2023.

We’re still working on the landing page, but here’s the full description of the series:

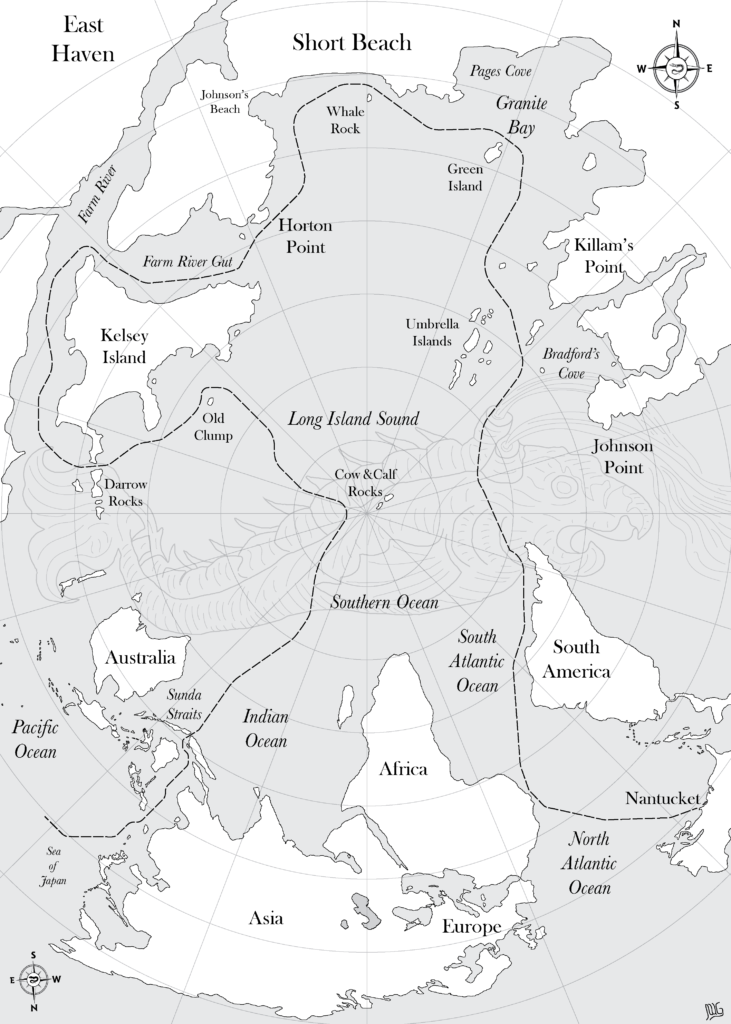

The Blue Humanities is a book series about humans and water, in all the forms that both of these assume and create. Re-examining relations between human and watery spaces, the books in this series explore waterscapes in dialogue with landscapes from cultural, social, historical, theoretical, literary, symbolic, aesthetic, and ethical perspectives. These books will engage with the multivalent meanings of salt and freshwaters and the compounded changes that waterscapes are undergoing today. The series will present new research on postmodernist, hydrofeminist, new materialist, posthumanist, postcolonial, and new historiographic approaches to the poetics of water. Since the Blue Humanities is transdisciplinary and methodologically diverse, interacting with marine and freshwater sciences, the series will contribute significantly to the future direction and reorientations of broader discourses in environmental studies.

The Blue Humanities emerged in the early twenty-first century as part of larger efforts to reimagine environmental thinking for the Anthropocene. This book series aims to support many kinds of diversity, from the cultures, methods, and geographies of its authors to the kinds of water each project explores. We encourage proposals that engage non-Western and non-canonical sources, as well as projects that reimagine the familiar in new ways. We particularly encourage creative-critical approaches, including collaborations between academic discourses and the arts, sciences, political activism, public humanities, and other modes of thinking. We are interested in monographs, collaborative books, and essay collections, including reconceived versions of those traditional forms.

Please reach out with queries or proposals to either or both editors (Steve Mentz and Serpil Oppermann) or to our Bloomsbury editor Ben Doyle.

Soon we hope to announce the members of our Editorial Board – stay tuned!

Please reach out with queries or proposals for the series, and circulate this information widely! We are so excited to talk with many of the great people who are thinking about water, humans, worlds, and cultures!