It’s time to move the list from my Reading List app over to the Bookfish. It’s not looking as if I’ll finish A History of Water by Edward Wilson-Lee before the New Year, partly because I’ve been distracted by the stunning new Dylan tome, Mixing Up the Medicine.

Here’s the list, with my special favs in bold.

In a separate post, my four favorites of the year: Energy at the End of the World, Birnam Wood, Fire Weather, and Noah’s Arkive.

January (7)

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

The Brain’s Way of Healing by Norman Doidge

Aquaman and the War Against Oceans by Ryan Poll

The Value of Ecocriticism by Timothy Clark

Appleseed by Matt Bell

Risingtidefallingstar by Philip Hoare

Pirate Enlightenment by David Graeber

February (8)

Data Driven: Truckers, Technology, and the New by Karen Levy

We Are All Whalers by Michael Moore

Fully Automated Luxury Communism by Aaron Bastani

Storm in a Teacup by Helen Czerski

I Know There Are So Many of You by Allain Badiou

The Wife of Bath: A Biography by Marion Turner

Blue Jeans by Carolyn Purnell

Racism without Racists by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

March (11)

The Wife of Willesden by Zadie Smith

Mad About Shakespeare by Jonathan Bate

The Lodger by Charles Nicholl

Reading Underwater Wreckage by Killian Quigley

Solarities: Seeking Energy Justice by the After Oil Collective

Radical Wordsworth by Jonathan Bate

Portable Magic by Emma Smith

God Human Animal Machine by Meghan O’Gieblyn

Spare by Prince Harry

Water Nature and Culture by Vernoica Strang

Fly-Fishing by Chris Schaberg

April (10)

Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris

Mushroom by Sara Rich

Hamnet by Maggie Farrell

The Thinking Root by Dan Beachy-Quick

The N. of the Narcissus by Joseph Conrad

Shipwrecked: Coastal Disasters and the Making of the American Beach by Jamin Wells

How to Live: Or a Life of Montaigne in One Question… by Sarah Bakewell

The Environmental Unconscious by Steven Swarbrick

Not Too Late by Rebecca Solnit &c

Hydronarratives: Water, Environmental Justice by Matthew Henry

May (8)

Briny by Mandy Haggith

*a New English Grammar by Jeff Dolven

The Earth Transformed by Peter Frankopan

Paved Paradise by Henry Grabar

Traffic by Ben Smith

William Shakespeare: A Brief Life by Paul Menzer

The Lightkeepers by Abby Geni

Kitchen Music by Lesley Harrison

June (8)

Bright Star, Green Light by Jonathan Bate

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

Borges, Between History and Eternity by Hernan Diaz

Fire Weather by John Vaillant

Noah’s Arkive by Jeffrey Cohen and Julian Yates

The Wager by David Grann

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

Building a Second Brain by Tiago Forte

July (13)

The Swimmer by Patrick Barkham

How to Be Animal by Melanie Challenger

The Charisma of Animals by Greg Maertz

Hanging Out by Sheila Liming

Running by Lindsay Freedman

The Heat Will Kill You by Jeff Goodell

Grief is the Thing With Feathers by Max Porter

Does the Earth Care? by Mick Smith and Jason Young

Sea Change by Christina Gerhardt

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting by Milan Kundera

Land Sickness by Nikolaj Schultz

The Deepest Map by Laura Trethewey

Open Book in Ways of Water by Adam Wolfond

August (11)

Dreamscapes and Dark Corners by Melissa Ridley Elmes

Saving Time by Jenny Odell

On Wilder Seas by Nikki Marmery

A Blue New Deal by Chris Armstrong

The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy

Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy

The Great White Bard by Farah Karim-Cooper

A Book of Waves by Stefan Helmreich

The Quickening by Elizabeth Rush

Adventure: An Argument for LImits by Chris Schaberg

The Big Melt by Jeff Goodell

September (16)

The Rigor of Angels by William Eggleston

Angry Weather by Friederike Otto

The Man Who Invented Fiction by William Eggleston

Dayswork by Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel

Naamah by Sarah Blake

Gramsci at Sea by Sharad Chari

Shakespeare in a Divided America by James Shapiro

Reading Pride and Prejudice by Tricia Matthew

Undoing the Grade by Jesse Stommel

Oceaness by Michael Blackstock

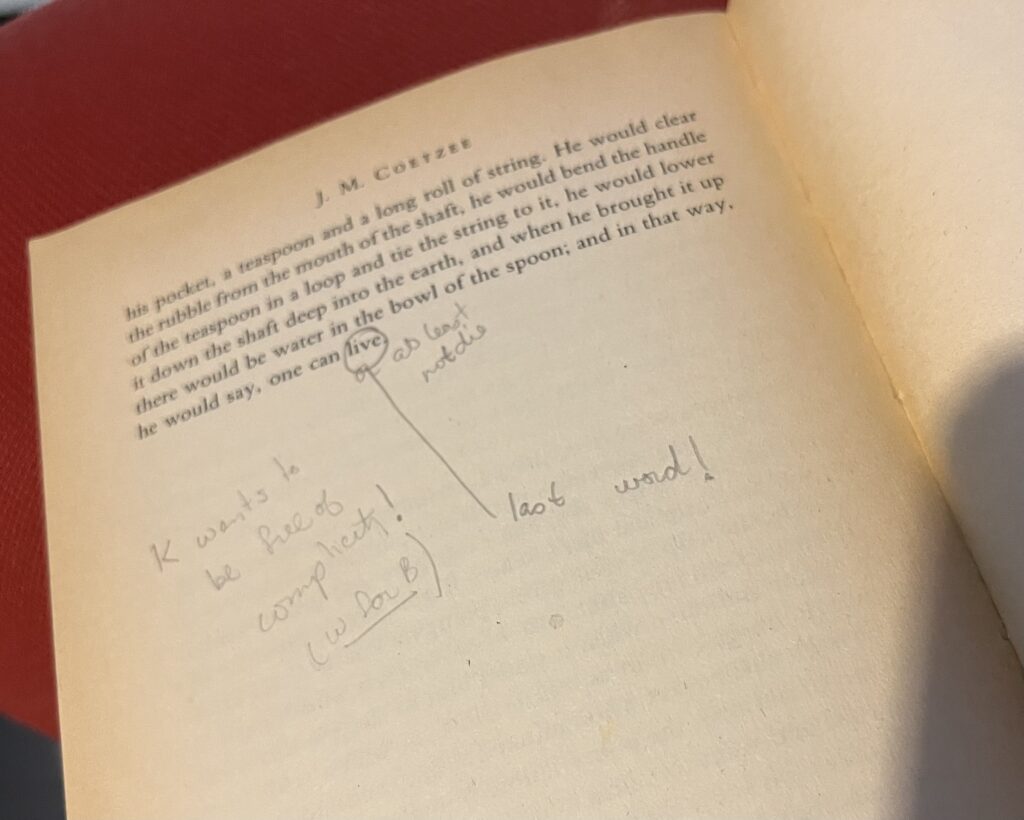

The Pole by J.M. Coetzee

Contested Will by James Shapiro

Her Lost Language by Jenny Mitchell

Youth by J.M. Coetzee

Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us by Simon Critchley

Summertime by J.M. Coetzee

October (13)

The Iliad trans Emily Wilson

Our Fragile Moment by Michael Mann

No More Fossils by Dominic Boyer

Anthropocene Blues by John Lane

Black Earth by Osip Mandelshtam

The Maniac by Benjamin Labatut

Venomous Lumpsucker by Ned Beauman

War and the Iliad by Simone Weil and Rachel Bespaloff

Upstream: Selected Essays by Mary Oliver

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Energy at the End of the World by Laura Watts

Aquatopia by May Joseph and Sofina Varino

Sandy Hook by Elizabeth Williamson

November (12)

White Holes by Carlo Rovelli

Ecological Poetics, or Wallace Stevens’s Birds by Cary Wolfe

Tides by Jonathan White

Cosmodolphins by Mette Bryld and Nina Lykke

Anaximader and the Birth of Science by Carlo Rovelli

The Bathysphere Book by Brad Fox

Democracy Awakening by Heather Cox Richardson

Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz

Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe

Silent Whale Letters by Ella Finer and Vibeke Mascini

Sand Talk by Tyson Yunkaporta

Helgoland by Carlo Ravelli

December (9)

The Cause of All Nations by Don Doyle

Baumgartner by Paul Auster

How to Be: Life Lessons from the Early Greeks by Adam Nicolson

Ways of Being by James Bridle

Voices in the Ocean by Susan Casey

The Sea: A Philosophical Encounter by David Farrell Krell

Number Go Up by Zeke Faux

AI and Writing by Sid Dobrin

Will to Power : The Great Courses Lectures by Robert Solomon

Total books read in 2023 = 126