Shakespeare without words may be an acquired taste, but I loved this compression of Macbeth into sixty minutes of funny, moving, mostly-silent and richly tactile performance. The post-show talk-back with the two performers was great fun too!

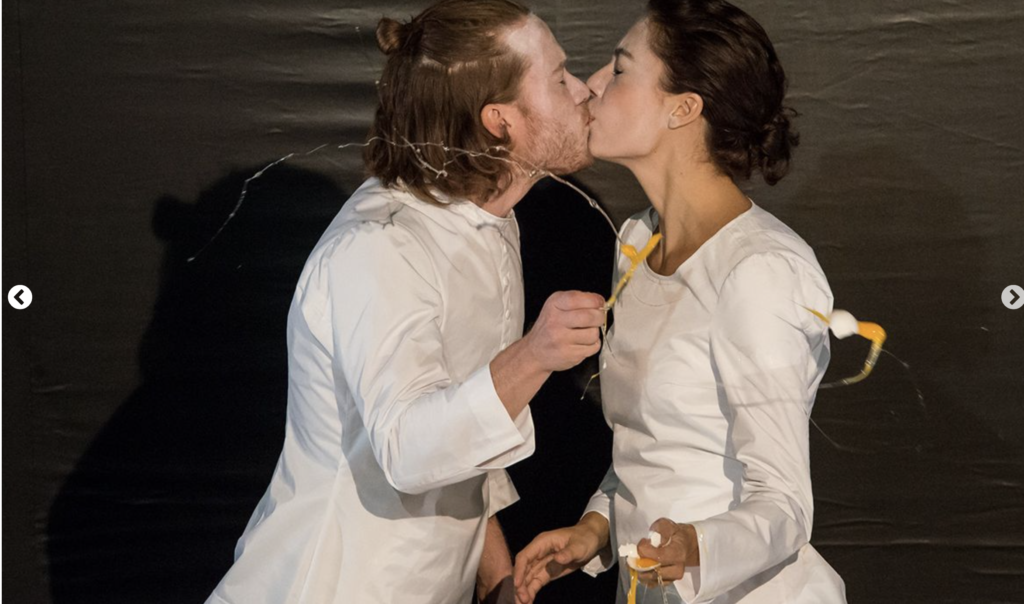

La Fille Du Laitier (in English, The Milkman’s Daughter) is a Francophone theater company based in Montreal. They first developed Macbeth Muet (Mute Macbeth) out of a five-minute silent performance. Now, about 150 performances later, it has grown to fast hour long. A slightly varied cast – the original production was created by Marie-Hélène Bélanger Dumas and Jon Lachlan Stewart, last night’s was performed by Marie-Hélène and Jérémie Francoeur – has developed a great combination of puppetry, mime, and call-backs to the techniques and melodrama of silent film.

In the talk-back, Marie-Hélène and Jérémie admitted to reading Shakespeare in French in high school, but said that they wanted to get to the emotional core of each scene. In perhaps the most intense moment of the show, Jérémie dramatized the murder of Lady Macduff by whacking a silver oven mitt, which represented Lady Macduff, repeatedly on the table. Jérémie emphasized that they had tried many different actions to represent this brutal murder, and that some – he did not say what they were – had been too emotionally visceral to perform.

Both Jérémie and Marie-Hélène, who played all the parts but mainly the violent power couple, were amazingly versatile and moving. But in some ways I thought the star players were a couple of dozen eggs. Building off a line in 4.2, in which a murderer calls Macduff’s son, “You egg,” before killing him, Macbeth Muet uses a few cartons of eggs to represent children. In the first of three flashbacks, the Macbeths’ efforts to have children of their own crack and spatter in their fingers. In the second, Banquo loses his wife but saves one egg. In the third, the carefully-nested eggs of the Macduff family get brutally squashed. Raw eggs, it turns out, are immensely evocative props – fragile when whole, sticky when broken, familiar yet mysterious. In her madness Lady Macbeth fingers and then breaks a hollow blown eggshell. It’s the last straw. I’m not sure I’ve seen a more powerful evocation of lost children in this lineage-obsessed and child-killing play.

I’ll mention one other moment in which the play almost-touched Shakespeare’s text. For audience members like me, following along scene by scene and often line by line, it was clear how closely the action mirrored the play. One of the sharpest of these moments came after Lady Macbeth died. As Macbeth stood in grief, the pacing of the offstage beeps – electronic “beeps” were used throughout as cues to move on to the next action – started to speed up. Macbeth looked up toward the back of the auditorium where the lighting and cues were coming from. More beeps. Faster. He shrugged, looked around. What do you want from me?

That muteness seemed, to me at least, to stand in for some of Shakespeare’s most gloriously excessive poetry, in which he makes despair into beauty –

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Sometimes when I see Macbeth I worry that whatever star playing the title role won’t be able to reach the full heights of these lines. One of the most distinctive versions of it I can remember was Kenneth Branaugh, in a 2014 production at the Park Avenue Armory, appearing to intentionally fracture the rhythm, as if he were working against Shakespeare’s iambic orchestra. Something like that happened last night at the Iseman Theater in New Haven – a small actorly defiance, a turning-against the history of those famous lines, and finding in them something new.

It’s on for one more night tonight, courtesy of the Festival of Arts and Ideas! Tickets available! Go see it!