Let’s start with some spicy bites to get the taste in your mouth —

- One highlight was Nikki Crawford’s Tedra (Gertrude) in her short shorts and skimpy top getting a bit too close to Dave & Steph Hershinow, who were sitting in the front row. Tedra insisted that “you look down on me, don’t you?” The lady protested just the right amount.

- Of the several shout-outs to Big Will, I think my favorite was the moment when Billy Eugene Jones’s Rev (Claudius) rushed out to present a huge tray of BBQ, shouting in triumph, “It’s all in the rub!” Not to be out-done, Marcel Spears’s Juicy (Hamlet) quipped bitterly from the side-stage, “Ay, there’s the rub.”

- Maybe I’m just missing ribs after a half-dozen years as a vegetarian, but at the end of the night I kept repeating in my mind one of Hamlet’s snide remarks about his mother’s remarriage, in which he tells Horatio that “the funeral baked meats / Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables” (1.2.179-80). I especially love the adverb “coldly,” which describes the physical state of the leftovers while also voicing moral disapproval. But in Fat Ham, the meat is always hot, tender, dripping off the bone.

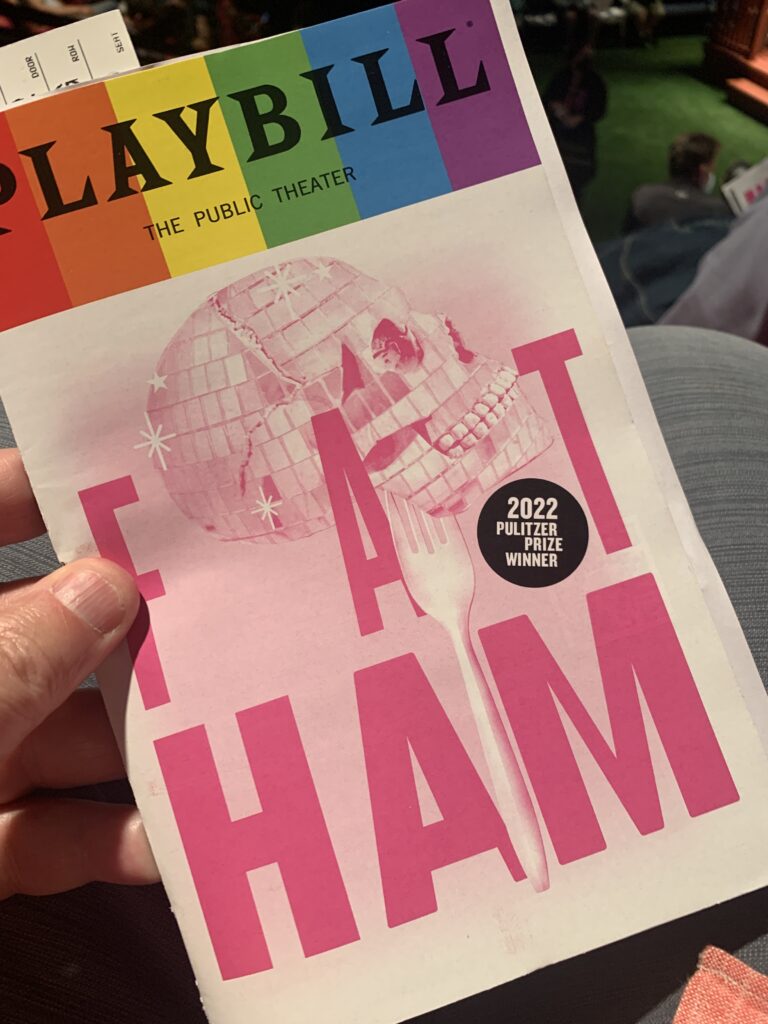

It’s a spicy, sweet play down at the Public Theater on Lafayette Street through July 15. I drove home thinking about smoked pork ribs as metaphors and material. The family business in James Ijames’s Pulitzer Prize winning play is barbeque, not Denmark. Killing swine to slow-smoke the meat and serve it in a tasty sauce makes a complex symbol for man’s work, but in Jones’s first moments on stage playing the ghost of Pap (Old Hamlet) he insists that it’s all about how you use the knife. He wants Juicy to butcher his uncle like a hog, “the way I showed you.” (Jones played both brothers, the dead Pap and the living Rev, in a nice casting touch that confused Juicy and titillated Tedra.) But if violence was Pap’s command to Juicy, Rev’s cooking and his dedication to making the meat succulent (did he ever say the meat was “juicy”? I’m not sure, but that’s the idea) suggested that violence isn’t the only way to make flesh tender. In Shakespeare’s play, Claudius is a Machiavellian mastermind. In Ijames’s, Rev is a good cook. Two different ways to modify the flesh around you!

According to both the dead father and the live uncle, the problem with Juicy, is that he’s “soft.” But the truth is, everyone in the play wants bites of tender flesh. Especially Juicy’s! (A note I found the next day in the Playbill, from the playwright: “This play is offering tenderness next to softness as a practice of living.” Soft and tender does it…)

[The spoilers start here, so if you’re planning to get downtown by July 15, maybe wait to read more…]

We all know Hamlet operates through hidden trauma – the prince’s inner curse may arise from ghostly visitation, existential insight, or blood-deep melancholy, but the lure of some hidden knowledge is the thing that centuries of actors and audiences have tried to dig into. In Ijames’s brilliant generational twist on Shakespeare’s paradigmatic structure, Juicy’s secret is queerness. But it turns out that everyone knows about it already — “You like boys, right?” says his straight-talking Mom, about mid-way through the action — and besides all the second-generation figures in this story are queer. Adrianna Mitchell’s Opal (Ophelia) and Juicy love each other, but they’re not looking for any cis-het action. Calvin Leon Smith’s Larry (Laertes) starts deep in the closet, in military uniform, while stoned Tio (Horatio), performed when I saw the show by the brilliant understudy Marquis D. Gibson, is so liberated that he debates a career in online porn before his show-stopping performance of an erotic encounter with a video game. In a world where the adult men are murderers, hog butcherers, and overly dramatic cooks, the queer generation rejects the drives and ambitions that Pap and Rev represent. Nobody wants to inherit this BBQ!

Plays are systems and characters aren’t people, so I don’t have favorite characters in Hamlet. But if I did they would be Gertrude and Polonius, played here as a pair of knowing, show-stopping women. Tedra (Gertrude) in shorts and a halter-top pranced about the stage, while Benja Kay Thomas as Rabby (Polonius) was resplendent in a purple dress and o’er-spreading hat. The two women formed an excessively hetero-sexed bridge between the killing and cooking older men and the queer kids. I loved seeing these two play as a team.

Juicy holds a kitchen knife a few times, and he fake-boxes with Rev, but he’s not the killer that Shakespeare’s hero perhaps reluctantly becomes. Juicy repents his one supreme moment of cruelty, outing Larry to his family, but at the play’s end it turns out that having one’s true self exposed isn’t destructive — in fact it enables a cross-dressed Larry to capture center stage for the final dance number. In Ijames’s dramatic world, you don’t have to kill or cook to survive. Playing is the thing, and also singing.

The bad old Rev still to go, and in a delicious pun he chokes on his own delectable pork rib. Juicy attempts a Heimlich, since he seems to be the only one who knows how to do it (perhaps because of his few semesters in Human Relations online at the University of Phoenix?), but Rev pushes him away in a bout of homophobia that, quite rightly, prevents his future breathing. Once the old man is down, the assembled cast seems ready to follow well-read Juicy’s instructions about how the story ends: “we’ll all kill each other.” Opal, who had always wanted to be a marine like her brother Larry, seems quite keen on some bloodshed. But then Juicy, in a glorious moment of intertextual revelation and discovery, realized that the group didn’t have to follow the old tragic story anymore. Why not live, instead?

Before the play, I had dinner with my friend and one-time teacher, Susanne Wofford, whose class on Shakespeare in the summer of 1994 changed my life and set me down the professional path I’m on now. She mentioned that she felt that Hamlet has become, in recent years, the most omnipresent of Shakespeare’s plays. She wasn’t sure why. There’s a way, it seems to me, that plays like King Lear and The Tempest may speak more directly to the looming ecological catastrophe of the present day. But after watching Fat Ham, I drove home to the utopia of coastal Connecticut thinking that Hamlet, perhaps more than any other tragedy, represents a vision of politics and succession as a prison, a locked box from which there is no escape. That no-future world feels perilously close today. The innovation of this brilliant, funny, exuberant response to Shakespeare was to unlock the box, to imagine a future of queer possibilities, to give into excess, and to laugh.

It’s not always clear to me, as we limp through pandemics, heat waves, and sclerotic politics, that we can follow Juicy’s turn into a happier generation. But I’d like to think so!

What a show!