Arcadia’s got the beat. “Habemvs Percvssio,” the inscribed arch proclaims in the opening number of Broadway’s only current musical based on an Elizabethan prose romance. The show starts with the most famous of the many Go-Go’s numbers that make up the musical backstory. “We Got the Beat,” the cast self-celebrates in the opening number Why not?

Arcadia’s got the beat. “Habemvs Percvssio,” the inscribed arch proclaims in the opening number of Broadway’s only current musical based on an Elizabethan prose romance. The show starts with the most famous of the many Go-Go’s numbers that make up the musical backstory. “We Got the Beat,” the cast self-celebrates in the opening number Why not?

I was probably the only person watching “Head over Heels” in the admittedly not quite full Hudson Theater on Tuesday night who was wondering how well the 1980s pop rhythm matches the Renaissance fixation with Arcadia as ideal place. In Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, the brilliant & intricate Elizabethan prose narrative that was the primary source for the musical & that I wrote my dissertation about in the early 1990s, the region is known “partly for the sweetness of the air and other benefits” but even more for “the moderate and well tempered minds of the people.” That ideal temperance, of course, gets remixed in the sixteenth-century story, as in the twenty-first century musical.

Maybe having “the beat” isn’t a bad way to think about Arcadian pastoral? It doesn’t mean you have all the secrets or have built full utopia — it’s just that songs are brighter, the weather fresher, life a bit tastier, in Arcadia. Or on Broadway.

Peppermint the Oracle

The modern version, written by Jeff Whitty and recently revised by James Magruder, is now on Broadway after earlier turns in San Francisco and, originally, at Ashland, OR. Its Arcadia presents a paradise of sexual plurality. The most rousing applause of the night was for trans actor and alumna of Ru Paul’s Drag Race Peppermint’s performance of the Pythian Oracle. The show’s narrative makes pretty messy hash of Sidney’s more balanced and more complex symmetries, including cross-dressed Amazon, a pair of contrasting princesses, and a royal pair who each fall in love with the visiting Amazon, the Queen because she realizes he’s a man under his armor and the King because he does not. (That final twist, along with the Oracle describing it, comes directly from Sidney, though other parts of the plot depart from both of the Renaissance versions of the narrative.)

The show was infectious and fun — and in some ways its sex-positive and erotically plural message almost fits the Elizabethan original, in mood if not words. Back in 2003, I wrote one of my first published articles on the cross-dressed Amazon figure, who I took as representing both gender uncertainty and generic multiplicity. Drawing gender and genre together via the Latine generare, I explored how Sidney’s multiply-revised text asks for plurality in both sexual presentation and literary genealogy.

The Broadway musical, like Elizabethan prose fiction, is a wonderfully flexible genre that loves to trot out its typical figures: Basilius the vain king, Gynecia the smart and cynical Queen, Dametas the fond father, Pamela the bossy older sister, Philoclea the “plain” (not really) younger sibling. I mostly enjoyed the Broadway-fication of the Arcadian tropes, and it was hard not to be swept away by the singing and showmanship, especially of Bonnie Milligan as Pamela, making her Broadway debut.

I wasn’t thinking of the big stage when I wrote my chapter on the Arcadian Amazon around the turn of the last century, but after seeing “Head over Heels” I could not resist looking back at my argument this week, many years since I’ve last re-read any of the versions of Sidney’s Arcadia. The article is “The Thigh and the Sword: Gender, Genre, and Sexy Dressing Sidney’s Arcadia,” in Constance Relihan and Goran Stanivukovic’s collection, Prose Fiction and Early Modern Sexualities in England, 1570-1640 (Palgrave, 2003). I was surprised to find that at least some of my claims for Elizabethan fiction also work somewhat for Broadway musicals — or am I just giving myself an Arcadian benefit of the doubt?

I suggested that Sidney’s cross-dressed Amazon, who in his version in the young prince Pyrocles (in the Broadway version he’s the shepherd Musidorus), celebrateshybridity in both gender — as in the stage version, she (Sidney uses both gendered pronouns in different contexts) seems happy to be both — and in genre. Here’s a resonant proto-feminist line, spoken by the Amazon as she/he/they do battle against the mono-masculine knight Anaxius:

I seem to have taken a picture of the wrong billboard on 44th St

‘Thou dost well indeed,’ said Zelmane, ‘to impute thy case to the heavenly providence, which will have thy pride find itself, even in that whereof thou art most proud, punished by the weak sex which thou most contemnest’

The Amazon on stage last night, who went by Sidney’s alternate name Cleophila, never voiced such Latinate periods. But I couldn’t help feeling that the show’s rage for plurality, for more love in more forms, wasn’t that far from Sidney’s “idle work,” even if the Elizabethan courtier himself, who would die heroically in battle not long after putting aside the unfinished Arcadia, might not have wanted to admit it.

Go see it before January 6, if you’re in New York!

Maybe it’s just that I’ve seen Fiasco’s

Maybe it’s just that I’ve seen Fiasco’s

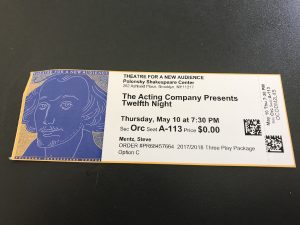

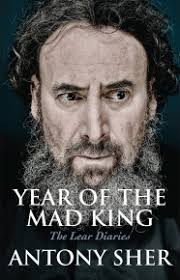

I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of

I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of

This tender love story between man and corporation won’t break your heart — we all know what happens when the company relocates to Mars, where office space is cheap — but the show gets down inside you and does its work. It’s as sharp and funny a take on today as you’re likely to find. If you’re in New York this weekend, get to Joe’s Pub to see it. The

This tender love story between man and corporation won’t break your heart — we all know what happens when the company relocates to Mars, where office space is cheap — but the show gets down inside you and does its work. It’s as sharp and funny a take on today as you’re likely to find. If you’re in New York this weekend, get to Joe’s Pub to see it. The