When I left the theater around 10 pm, the rain fell heavy and thick, splashing hard onto my bald head. I darted beneath trees but was pretty wet by the time I got to my car. I missed my exit for the Whitestone Bridge and had to navigate a few treacherous puddles as I made a U-turn around the LaGuardia exits. Allegories abound in wet places: was I replaying the show, or extending it, or asking for a slight variation?

When I left the theater around 10 pm, the rain fell heavy and thick, splashing hard onto my bald head. I darted beneath trees but was pretty wet by the time I got to my car. I missed my exit for the Whitestone Bridge and had to navigate a few treacherous puddles as I made a U-turn around the LaGuardia exits. Allegories abound in wet places: was I replaying the show, or extending it, or asking for a slight variation?

The Unisphere

The skies hadn’t been clear when I got to the Queens Theater a little before 7 pm to meet my students, but my Dark Sky app thought the storm might hold until midnight. I did arrive to an amazing water-show: the fountains surrounding the Unisphere, the 140′ high globe constructed for the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, were switched on. I’d never seen them flowing before. I walked partway around the massive orb — the downwind side was torrential — and it was an amazing site. The massive sphere was dedicated in 1964 to “Man’s Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe” — which, come to think of it, makes an interesting comment on the ideological fantasies under examination in The Tempest. The jets of water shooting maybe 75 feet into the air resembled so many wet Ariels, performing the best pleasures of the wizards who built the Unisphere.

I heard a great World’s Fair story last night too: it turns out that a retired man who’s been auditing my Shakespeare classes off and on for the past few years, via a St. John’s community outreach program, had worked as a waiter in the Indonesian pavilion when he was a high school student in the summer of 1964. He described taking a motorized scooter home each night from the Fairgrounds to Forest Hills weighed down with change from tips, which would eventually overflow his sock drawer at home. He wore his marathon entrant’s cap last night, as he was getting ready to run his twenty-fifth consecutive (!) New York City marathon this Sunday.

Astrida Neimanis at Whale Creek

Unisphere motto = “Man’s Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe”

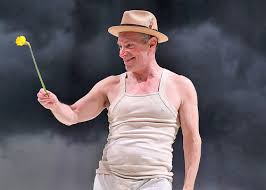

The highlight of Titan Theatre’s Tempest was Devri Chism’s compellingly nonhuman Ariel. She opened the show by dancing the storm into shipwreck, and throughout the night she repeatedly controlled the audience’s attention. Perhaps her most memorable trick was a subtle practice of holding her face at an oblique angle to the other actors on stage, emphasizing the intensity and partial incomprehension of her gaze. While many of the other performances were open and accessible — I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a more innocent rendition of Miranda than Ann Flanigan’s — Chism’s Ariel was the one performance who kept us asking for just a little bit more.

About the enter the Nature Walk

I came to the stormy show after an afternoon in post-Nature, walking my favorite toxic pathway on the borderlands between Greenpoint and Long Island City on the Newtown Creek Nature Walk. I’ve not been back for a while, but all my favorites were there: the epochal steps, the sludge barge, the hidden oil mayonnaise deep below. I was lucky to have been able to convince one of my most-admired blue humanities scholars Astrida Neimanis to join me for the walk. She’s a brilliant and inspiring eco-hydro-feminist based in Sydney, Australia who I just learned a few days ago was in New York for a talk on Thursday at the Pratt Institute. I’d got the news too late to get to Pratt, but it was fantastic to finally meet her in person. We talked about Newtown Creek, about post-Nature and the sublime, about an amazing-sounding project she’d put together last summer with Cate Sandilands in Canada. It’s hard to catch up with our fellow environmental humanists who live so far away, and I felt lucky to have managed it. Plus Newtown Creek is where I want to bring all my academic friends — I actually had a plan to drag an MLA panel out to it last winter, but sub-zero temps trapped us in midtown.

Driving home through the storm, I tried to salvage Terry Layman’s Prospero. As a student suggested to me after the show, he looked right — tall, white-bearded, Gandalf-ish. He garbled some lines and stepped on enough of his fellow actors’ cues that I wondered if it was intentional, a way of signaling the bully-Dad’s desire to control his human and nonhuman children. But they played his love for Miranda conventionally, and even Caliban got forgiven in the end. I wasn’t fully convinced: Prospero is a tough part to play well in these ambivalently post-imperial and I-wish-we-could-be-post-patriarchal days. I’m still waiting for someone to hit it just right.

Steps under water at Newtown Creek

The show is up for another week, and very much worth a trip to Corona Park! Go early to walk around the World’s Fair grounds and think a little about the “Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe” — it’ll put you in the right mood!

Near Newtown Creek

Olivia and I decamped at the interval due to heat, impending murders, and in deference to her desire to see the big city after being cooped up in Stratford all week. So my thoughts of the Globe’s Othello end with 3.3, perhaps the most brutal and brilliant scene Shakespeare ever wrote, which takes the Moor from happy husband to sworn homicide. I would have liked to have seen the close, but I know how it ends!

Olivia and I decamped at the interval due to heat, impending murders, and in deference to her desire to see the big city after being cooped up in Stratford all week. So my thoughts of the Globe’s Othello end with 3.3, perhaps the most brutal and brilliant scene Shakespeare ever wrote, which takes the Moor from happy husband to sworn homicide. I would have liked to have seen the close, but I know how it ends!

Heading off to JFK this evening for a night on Delta’s big steel bird, but the

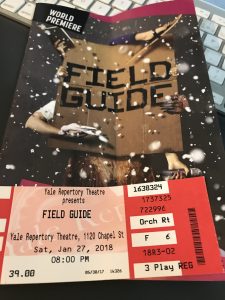

Heading off to JFK this evening for a night on Delta’s big steel bird, but the  I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of

I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of

When I was a teenager, just about my son’s age now, I churned through a bunch of the big Russian doorstopper novels: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol. (I didn’t get to Bulgakov until much later.) What I remember most about The Brothers Karamazov was the humor: a goofy, earnest melodrama that finally turned into a near-spoof of a trial scene, in which the unsuccessful defense lawyer’s arguments on behalf of the (technically innocent but morally guilty) Dmitri rotated around some quite silly chapter titles: “There was no money, There was no robbery” (4.12.11) and “And there was no murder either” (4.12.12).

When I was a teenager, just about my son’s age now, I churned through a bunch of the big Russian doorstopper novels: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol. (I didn’t get to Bulgakov until much later.) What I remember most about The Brothers Karamazov was the humor: a goofy, earnest melodrama that finally turned into a near-spoof of a trial scene, in which the unsuccessful defense lawyer’s arguments on behalf of the (technically innocent but morally guilty) Dmitri rotated around some quite silly chapter titles: “There was no money, There was no robbery” (4.12.11) and “And there was no murder either” (4.12.12).