The visible work of this book is easily and briefly enumerated:

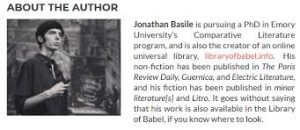

The most compact way I know to express Jorge Luis Borges’s brain-bending irony slides in between the second and third words of the title of his essay, “A New Refutation of Time.” The title creates a compact version of the self-canceling liar paradox credited to the ancient philosopher Epimenides: if the essay’s argument is “new,” time has not been refuted, but if the “refutation” does what it claims and deconstructs time, the modifying word “new” becomes meaningless. So far, so self-consuming. Borges’s essay, like many of his fictions, dances across the edges of veracity and what Jonathan Basile, in Tar for Mortar, his brilliant new open-source reading of Borges, calls “the dream of totality.”

Basile, the creator of the amazing libraryofbabel.info website that digitally replicates the conditions of Borges’s famous story, “The Library of Babel,” brings to this book multiple strengths: razor-sharp analytical skills, precise writing, and a web-master’s experience of wrestling with a digital instantiation of Borges’s thought experiment. He’s written a brilliant book about Borges — that would be enough of a great thing for me — which also has important things to say about intellectual ambition, irony, language, and the things that the Digital Humanities can and cannot reveal.

… An examination of the essential metric laws of French prose, illustrated with examples taken from Saint-Simon (Revue des langues romanes, Montpellier, October 1909)

What Basile terms the “dream of totality” turns out, as he cogently shows, to be quixotic in a very precise way: the fantasy never corresponds to reality, but the act of dreaming changes the world in which the dreamer lives. “Totality itself,” Basile observes, “is essentially incomplete” (17). This lack of wholeness redounds upon the dreamer. “In all its forms,” he continues, “the library should lead us to think differently about the possibility of originality or novelty” (17). The limits of both Borges’s Library and language itself — the fact that “even the most unpredicted or unpredictable event is intelligible to us only by means of conforming to pre-existing concepts and forms of experience” (18) — bounds our thinkable universe. The world spreads itself before us, in physical space and also inside the slim & somewhat broken copy of Borges’s Labyrinths that I have sitting on my desk right now. The fragile New Directions paperback is the second of several copies that I have owned, but the oldest still in my possession. My notes in spidery pencil marked the pages in the mid-1980s, when I treated myself to an undergrad course on Borges and Latin American fiction with James Irby, who translated most of the material in this volume. Around that same time that I changed tracks from my plans to major in theoretical mathematics and turned instead to literature, where I remain today.

… A reply to Luc Durtain (who had denied the existence of such laws), illustrated with examples from Luc Durtain (Revue des langues romanes, Montpellier, December 1909)

“I no longer long for a solution” (18), Basile writes after a wonderfully thorough analysis of the possible and impossible structures of “The Library of Babel.” He comes to think that “Borges has an imagination that surpasses lucidity to its dark hinter-side, the mind of what I would prefer to call an anarchitect, whose great vision was an ability to lead us into blindness” (18). At the far end of the paradox lies “Borges’s irony” (18) and his habit of breaking open all conceptions of totality even as he dreams them in their fiercest and most capacious forms. At the end of Basile’s gorgeous investigation and careful parsing of “The Library of Babel,” he arrives at Borges’s auto-ironic not-quite-nihilism: “there is no universe in the organic, unifying sense of that ambiguous word” (64). In an odd moment of vertigo that I associate with a lifetime of reading Borges, I noticed when I first read that quoted sentence — at the hinge of Basile’s book — that the passage was one I’d also quoted myself, at the conclusion of the “Brown” chapter I wrote for Jeffrey Cohen’s Prismatic Ecology in 2013 — a chapter and book that also marked a redoubling or intensifying of my own ecomaterialist turn.

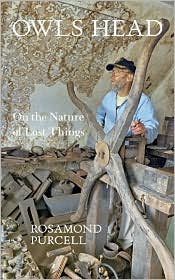

The broken spine of my undergrad copy of Labyrinths

… almost infinitely richer …

Repetition looks different under a Borgesian lens. It’s not very strange that Basile and I, two American Borgistas, would quote the same resonant phrase. In its playful doubling of universal meaning, the phrase perfectly captures Basile’s argument about irony and totality; I used it to make a similar point about environmental identity and excess. But the echo worked on my imagination as I turned into the second chapter of Tar for Mortar, which moved from an explication of the experience of creating libraryofbabel.info and a comparative reading of “self-contradiction” in Borges and Nietzsche regarding the Eternal Return. Now I started to get suspicious, and I opened the title page of my mid-’80s copy of Labyrinths to the notes for what would become my final paper in that course: “the Eternal Return / see last pp. of ‘Garden.'” I didn’t know much about Nietzsche at that time — I would have benefited greatly from Basile’s cogent explication in this book! — but I foisted on James Irby at the end of that long-ago semester many pages of undergraduate Borgesiana, circling around Eternal Returns and paradoxes of space and time. I’ve long since lost the paper itself, but my memory is that he thought I should maybe read more Nietzsche, but he appreciated my enthusiasm for Borges.

There is no exercise of the intellect which is not, in the final analysis, useless.

Basile finds in Nietzsche and Borges examples of “text[s] at odds with [themselves]” (82). The ironic, self-negating core of both authors, and their common sources in the atomist tradition in philosophy, require what Basile wonderfully terms “a sly self-assurance when expressing themselves by means of contradiction” (86). In Nietzsche, the characteristic mode is aggressive “affirmation” (86) in the face of impossibility. For Borges, the characteristic turn exits pure philosophy for aesthetics and fiction: his muse-mouthpieces are not the prophet Zarathustra, but more literary figures, Don Quixote, or his not-translator Pierre Menard. Or perhaps his abiding figure occupies the ironic separation the Argentine author described between himself and “the other one, the one called Borges, … the one things happen to” (“Borges y yo” Irby trans. 246).

Fame is a form of incomprehension, perhaps the worst.

The third and shortest chapter of Basile’s book takes up a question, “In Which It Is Argued, Despite Popular Opinion to the Contrary, that Borges Did Not Invent the Internet.” It’s a smart, witty reply to misreadings of Borges as prophet of digital utopia. Basile makes a compelling case that Borges’s works display “the deferral of presence across several virtualities” (87) rather than an anticipation of digital mediation in multiple modes. He instead argues that the central idea in Borges reveals “the rupture of a ceaseless differing-from-self” (91). In wonderfully compact prose, Basile concludes with an image of Borges as exploring “the lack of totality, the finitude and uncertainty that plague even the grandest project of any cognition shuttling between uniqueness and iterability” (92). But the lingering image with which the book closes is not this conceptual split but “the corner of the smile that recognizes in this finitude the possibility of all play” (92.)

Notes from the 1980s

Every man should be capable of all ideas, and I understand that in the future this will be the case.

There are a few writers I loved obsessively as a boy — maybe it’s just Borges and Thomas Pynchon for whom I feel this level of intensity — to whom I return eagerly and also apprehensively, with the awareness that what I found in these authors indelibly marked my younger self. I read Borges today with teenage Steve on my shoulder, wondering what he made of these texts then and how they changed him. I wonder how that reading and thinking translated me from a long-ago New Jersey suburb to where I am now. (Actually, I live now in a Connecticut suburb, so maybe I’m not that far away, though the decades and detours feel immense and labyrinthine.) I’m grateful to Jonathan Basile for his rich and brilliant investigation of this writer who means so much to me. All Borgistas, or really anyone who cares about literature, language, and speculative thinking, should read this open-access book. And support punctum books!

[All quotations in bold from James E. Irby’s translation of “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”]

The final “elegant hope” of the narrator of “The Library of Babel” imagines some eternal traveler making infinite peregrinations through the Library who would in inhuman time “see the same volumes were repeated in the same disorder (which, thus repeated, would be an order: the Order” (Irby 58). An universal and cyclical library would suture the paradoxical combination of maximum iterability in linguistic signs, “a number which, although extremely vast, is not infinite” (54), and extension in physical space. Like Basile and like Borges’s narrator, I’ve been turning that possibility over in my head for a long time. I’m so pleased to have revisited it in the good company of Tar for Mortar.