I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

SAA seminars are among my favorite academic events. Pre-circulating the papers, which all seminars do, and exchanging responses beforehand, which most do, means that you come to the event already part of a dynamic exchange, and the trick is to move everything forward. The two hours’ traffic of the seminar needs to make contact with all the distinct projects but not get bogged down by re-hashing material we’ve already covered in our e-exchanges. I used personal introductions, a hand-out, and a parlor game.

When we introduced ourselves around the table I asked, at this risk of bringing sentiment into scholarly life (!), for personal connections to the sea. I’m fascinated by the stories that flowed forth, from paternal stories of the navy to assorted maritime engagements and adventures. I talked about open water swimming. It took a fair amount of time to get all these stories out, more than if we’d just given names & academic homes, but that quick dip into our imaginative oceans primed us to think personally about the academic material that followed.

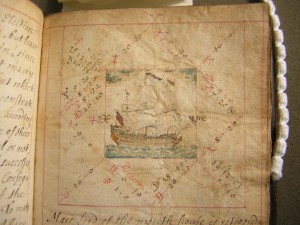

The parlor game involved me giving each seminar member a maritime term or phrase that has entered common speech — “from stem to stern” “doldrums” “aloof” “the bitter end” — and asking each participant to smuggle that word into our discussions, at which point the word-smuggler would triumphantly cast the printed term into the center of the seminar table. We never got to part two of this exercise, reflecting on how these words might represent or capture the deep interplay of metaphor and technical reality in the way we talk about the sea, but it was great fun. It also helped us make transitions, which can be awkward at these things. I used my phrase, “back and fill,” to shift us out of autobiographical maritime reflections and into Carl Schmitt’s Anglo-centric vision of maritime empire.

The seminar outline offered to a few general questions — Schmitt and empire, Glissant and the beach, an assortment of oppositions including metis/intellect, beach/whirlpool, and surface/depth — to get ideas circulating without tying them too explicitly to specific papers. We concluded, perhaps too easily, that we don’t like neat oppositions, though I also wonder if the desire to connect or blur oppositions isn’t in its own way as oversimplifying as the binaries themselves. The trick may be finding a way to think meaningfullly about difference and connection at the same time.

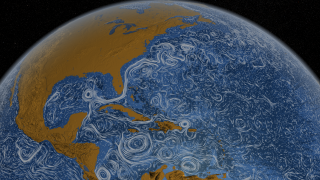

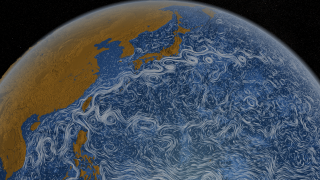

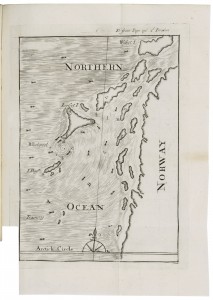

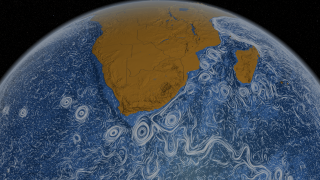

My job when navigating the 13 great papers and fantastic contributions of two non-Shakespearean respondents was keeping us off rocky shores, so my notes on the seminar outline aren’t terribly coherent. Some great stuff about cultural differences across different ocean basins, esp the Med / Atlantic / Pacific, and also the fresh/salt/estuary relationship — what to call it? A binary plus one? One interesting thing about estuaries is that their salinity changes with the tide and also with wind and weather, so they are perfect places to interrogate the fresh/salt distinction. There’s a way, as I was thinking some time ago, that this distinction maps onto local/global concerns: all fresh water questions are basically local, while salt water circulates globally.

The question of Shakespeare as such, interestingly and perhaps reveallingly, never really came up. Plenty of papers took up non-Shax-y topics and authors, and several seminarians used Shakespeare as a stalking horse for big questions about theatricality or ecology or the historical changes that accompany early modernity. Jeffrey Cohen hid his Bard-o-skepticism until he wrote his blog posts, where he has generous things to say about the whole event.

After the seminar, the rest of SAA was a blur of bars & plenaries, not always in that order. I very much liked the primatology panel with Holly Dugan & Scott Maisano, and thought the Fri morning plenaries were a bit bland in their admiration of all things SAA. Or perhaps I’m just no longer used to closing the bar, which makes me a bit cranky at a 9 am lecture!

I’m especially grateful to my two guest-interlopers, Jeffrey Cohen and Joe Blackmore, whose contributions did what I’d hoped they would do, stretching our discussion chronologically and linguistically and imaginatively. All academic conferences, even international ones like SAA, tend toward in-group parochialism, esp when our shared subject so often gets claimed as “not of an age, but for all time.” The idea of the seminar was not really to substitute “ocean” for “Shakespeare” in an all-embracing way, but to seek out fluid metaphorics — flows instead of spaces — that might enable us to deal with vastness and distance in different ways.

So — a new big thing for Oceanic Shakespeares? I’m not sure yet. But certainly wide horizons and strong winds blowing.