Some words I expect or hope or imagine that I’ll hear this Thursday evening at Oceanic New York:

- Bridge

- Ahab

- Glacial

- Industry

- Apocalypse

- Ishmael

- Epic

- Citizen Bridge

- Oyster

- Dead Horse

- Swim

- History

- Impossible

- Remediate

Some words I expect or hope or imagine that I’ll hear this Thursday evening at Oceanic New York:

What happens when you open the floodgates of the wonderworld and let the ocean onto campus?

Something like Silent Beaches, Untold Stories, Elizabeth Albert’s great show at the Geoffrey Yeh Art Gallery on the St. John’s Campus in Queens until November 9.

I’ve walked through the show twice so far, once with the curator, but I feel I’ve only dipped my toes into its expansive waters. At the bottom sits the rich historical stew of maritime New York. Exploring a series of New York’s forgotten, marginalized, or polluted waterfronts, from Dead Horse Bay to Newtown Creek to Hart’s Island, which still serves as the city’s potter’s field for the burial of unclaimed bodies, the show returns forgotten spaces to our eyes. Drawing on photographs from the Library of Congress, the Museum of the City of New York, the New York Public Library, and other sources, the items on display unveil a dissonant watery history that mingles industrial expansion with sailing ships, steel bridges with wooden boats. I kept looking for a picture of Ishmael at Battery Park, looking south, thinking about whales, facing away from skyscrapers.

These watery histories are poignant and powerful, but surfacing these pasts isn’t the only center of Silent Beaches. The historical materials are entangled with the work of contemporary artists who are exploring maritime New York. The materials include drawings by George Boorujy, a pair of stunning large-scale wood-block prints by Marie Lorenz as well as video from Lorenz’s Tide and Current Taxi project, which has been exploring the city’s waterways since 2005, a looping documentary film by citizen advocate and filmmaker Melinda Hunt, images of Mary Mattingly’s Waterpod project, and more. Moving through the gallery’s striking historical images, including a documentary film of New York’s riverside made by Thomas Edison to the playful and experimental work of twenty-first century artists provides an appropriately marine shock, as if the sands were shifting under our feet.

Art encrusted with local maritime history pushes all my buttons, but two more elements of Silent Beaches keep running through my head as I continue to think about the show.

The first, which I didn’t quite notice until the curator pointed it out to me last Thursday, is an audio piece, playing from a speaker in the far corner of the gallery. The tinkling, flowing sound was recorded at Dead Horse Beach at low tide, as the gentle surf washied back and forth over the accumulation of trash. The debris at Dead Horse comes from a landfill that’s long-since been capped, so the objects that remain on the beach are those that decompose slowly: glass, ceramics, some plastics. The music of ocean on glass, it turns out, is gorgeous, subtle, strangely soothing.

My favorite place of all in the exhibition, however, may be a glass case full of objects rescued from assorted New York beaches, many of which come from personal collections or recent scavenging trips. An old life-guard whistle from Staten Island. A couple of guns. The bones of dead horses. Heartbreakingly, a doll’s leg, the mate to which — but not the body — was found a little way down the beach.

So far, I’ve spent more time looking at this leg than any other single object in this great show. I like to look at it, think about it, savor its soft tones and the sheen that ocean water has given to its long-submerged plastic. I like to imagine its serpentine voyage from child’s toy to art installation. I’ll read a poem about the leg’s journey at the Underwater New York poetry reading at the gallery on October 29. A human-and-inhuman limb, returned from the sea, testifying without words.

Try to get to St John’s before November 9!

When schoolteacher-turned-whaleman Ishmael walked the streets of “your insular city of the Manhattoes,” he knew New York as oceanic city and commercial capital. Standing on the Battery looking south, he saw a cityscape “belted round by wharves as Indian islands by coral reefs – commerce surrounds it with her surf.”

Today commerce dominates but the surf lies hidden. This round-table event digs into New York City’s asphalt, pries up the streets, and finds underneath not beach, but – ocean.

Oceanic New York aims to recover traces of the salt-water past that still lies beneath New York’s urban feet. Taking inspiration from Elizabeth Albert’s gorgeous and startling exhibition, “Silent Beaches, Untold Stories,” — about which I’ll have more to say soon — we’ll plunge into the urban and the oceanic. “Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon,” entices Ishmael. Everywhere people stare toward water. “Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land,” says the mast-head philosopher. That’s where we want to be.

The twentieth century witnessed the drying up of New York: shifting the industrial port across the harbor to Newark, exhausting the oyster beds, turning South Street Seaport into a museum,. That’s where the mighty four-masted USS Peking sits today, her 170-foot steel mainmast dwarfed by skyscrapers. The twenty-first century, however, with its ecological crises, extreme weather, and growing recall of oceanic history, is returning to New York’s salt-water identity.

Drawing on the forgotten waterscapes of the city, the catastrophic floods of Hurricane Sandy, and still-wet histories and legends, these talks and conversations surface the oceanic substrata on which New York floats. Oceanic New York goes beyond insular Manhattoes to Dead Horse Bay, Breezy Point, Gravesend, Hell Gate Bridge. Anywhere salt water seeps into our shoes and stains our clothes.

Three weeks from today…

My main event this summer has been working my way through the final bits of my book-in-progress, Shipwreck and the Ecology of Globalization. A lively side-bar has been exploring a useful theorist for ecological globalization, Peter Sloterdijk.

Since my German isn’t up to the task, I’ve been keying off the useful Sloterdijk in English page that I found via Stuart Elden’s blog. There’s lots out there, and more in the pipeline. Terror from the Air, Rage and Time, and Stuart Elden’s collection Sloterdijk Now (2012) are sitting on my desk right now, and Spheres I is on its way. Neither Sun nor Death made a good introduction to the entire corpus.

The key work for my purposes, I think, will be Spheres vol 2: Globes, which isn’t out in English yet, but I’ve found a selection from it published as “Geometry in the Colossal: The Project of Metaphysical Globalization” in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27 (2009): 29-40. (It’s a translation by Samuel Butler of pp. 47-72 of Spharen II — Globen [Suhrkhamp, 1999].) It’s pretty exciting stuff & will make an appearance in the opening pages of the Shipwreck book, as well as at a talk I’ll give at GW MEMSI this coming fall.

Especially engaging for my purposes is Sloterdijk’s desire to locate globalization both as a historical phenomenon, linked to the maritime expansion of European cultures in the 15-17c, and also to see its influence enfolding in much earlier, and later, eras. It starts with Greek geometry:

If one were to express, with a single word, the chief motif of European thought in its metaphysical age, it could only be ‘globalization.’ The affair of Western reason with the totality of the world is created and unfolds in the symbol of the geometrically perfected round form, which we still signify with the Greek ‘sphere’, or more frequently with the Latin ‘globe.’ (29)

Geometry prefigures geography:

Globalization of sphereeopoise in general is the fundamental event of European thought, one that has not ceased to provoke revolutions in the thought and life relations of humans for two and a half thousand years….Mathematical globalization proceeds [sic] terrestrial globalization for more than two thousand years. (30)

In this totalizing perspective, which seems exaggerated but stimulating, spherical thinking shapes Western culture:

The representation of the world with the globe is the decisive deed of the early European enlightenment…the radical change to monospherical thought…the unity, totality, and roundness of existence…first comes the sphere, then morality (31).

I like the pressure Sloterdijk gets from abstraction here, the sense that an imagined form — the sphere as geometric absolute, a creature of the mind — puts pressure on lived historical experience. I don’t really believe pre-geometric or pre-Greek cultures were innocent of morality — what could that mean? — but I think the geometric imagination shapes (pardon the pun) cultural ideas about wholeness, centered-ness, conceptions of substance and weight.

This project is interesting to me because Sloterdijk also focuses on early modern maritime globalization. In his sphere-centered understanding, maritime expansion becomes less a question of radical “discovery” than of putting into physical practice a vision that has long been accepted & watching that vision assume tangible form:

…the fundamental thought of modernity was articulate not by Copernicus, but rather by Magellan. The fundamental fact of modernity is not that the earth orbits the sun, but rather that money circumnavigates the earth. The theory of the sphere is, at the same time, the first analysis of power. (33)

In making use of this material, I’ll want to tone down and refigure the “modernist break” language here, since globalization seems much more a “time knot” than a historical break: money circled much of the Eurasian / African world before Columbus & Magellan, and the epoch-hunting of “fundamental thoughts” seems a profitless game. But I agree that the conceptual unity of the globe assumes a changed resonance after maritime expansion into the New World, and especially after the establishment of global trade routes between the oceanic basins. It’s not the “invention” of something new, but the progressive re-interpolation or knotting together of old and changing things.

The core of Sloterdijk’s article / selection is detailed reading of the first-century Farnese Atlas, a Roman statue made after a presumed Greek original, now in Naples. Atlas supports a celestial globe on which half of the known constellations of the ancient world are visible (36); it’s the heavens, not just the earth, on the Titan’s laboring back.

Sloterdijk reads this Atlas as a philosophical athlete, because

a philosopher is one who, as an athlete of totality, is laden with the weight of the world. The essence of philosophy as a form of living is philponia — friendship with the entirety of weighty and worth things. The love of wisdom and the love of the weight of the one whole are unified (39).

In Neither Sun nor Death, Sloterdijk has a few nice oceanic nuggets that I might be able to use also —

People born today do not develop any oceanic consciousness — neither in the phobic nor the philobatic sense (239). (Cf At the Bottom, pix-x)

Moreover, from a historical viewpoint, the opposition between thinkers of down-to-earthness and thinkers of maritime situations remains pertinent — it is a contrast that has not ceased to widen since 16000. This division between these two types of thinkers is one of the most important factors in the psychodrama of modern reason….Among the theoreticians of emergent maritime situations the towering authors all lived in port towns — and this is no coincidence — whether we are talking of Montaigne, who, from Bordeaux, had a view of the Atlantic, or of Bacon, who, like a Pliny of early capitalism, even wrote a history of the wind (239).

A collective biography should be written of about the lives of those infamous men of the sea, those newly desolate people for having slipped out of our historical memories (241). (Cf Marcus Rediker)

Terrestrial globalization is the common work of astronomers, mathematicians, trades, mariners, and a plethora of dubious figures (198).

To which last group I’d add poets, playwrights, and other writers.

I’ve got lots more Sloterdijk to read, but it’s fun to get started.

The semester is almost upon us! One of the things I’m planning for this early fall is Oceanic New York, a Round-Table and Conversation event at the Yeh Art Gallery at St. John’s on Sept 26th. I’ll post updates via the Oceanic New York Page on this blog, and probably add a few things here as well.

Here’s the flyer: Oceanic New York Poster

And here’s what the Page has right now —

Welcome to Oceanic New York, a round-table and discussion that will take place in the Geoffrey Yeh Art Gallery on the St. John’s University campus in Queens on Th 9/26/13, from 6 – 8 pm.

We’ll be exploring the relationship between New York City and the Ocean, building our remarks variously from artistic, literary, eco-theoretical, or personal perspectives. The participants include academics and artists, sailors and swimmers, bridge-builders and castaways. We’re hoping to uncover watery connections between urban living and oceanic space.

The Gallery space where we’ll meet will feature Elizabeth Albert’s new exhibition, “Silent Beaches, Untold Stories: New York City’s Forgotten Waterfront.” We’re hoping to contribute to this show’s surfacing and re-figuring of the watery coastlines of NYC.

I’ll post previews and further information to this page as we get closer to the event. The round-table is free and open to the public.

Current participants include

Jamie Skye Bianco, NYU

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, George Washington U

G. Ganter, St. John’s U

Eilleen Joy, BABEL Working Group and Punctum Books

Allan Mitchell, University of Victoria

Nancy Nowacek, Artist

Karl Steel, Brooklyn College, CUNY

Marina Zurkow, Artist

The technical name is a perigee moon, or a perigee-syzygy of the earth-moon-sun system, which means that the full moon tonight brings the silver rock as close to earth on its elliptical orbit as it gets. These extra-full moons happen about every 14 lunar cycles, so not quite once a calendar year. A swimming tide after dinner happens about once every two weeks during the summer around here. Nice to have both together.

The technical name is a perigee moon, or a perigee-syzygy of the earth-moon-sun system, which means that the full moon tonight brings the silver rock as close to earth on its elliptical orbit as it gets. These extra-full moons happen about every 14 lunar cycles, so not quite once a calendar year. A swimming tide after dinner happens about once every two weeks during the summer around here. Nice to have both together.

The flood tide tonight will be 7.5 feet at 11:58 pm, which means the storm drains on Beckett Ave will flood & we might get water sloshing up over the sidewalk on Clark Ave.

A beautiful evening for the first night swim of the season.

What does the sea feel, I wonder, when that fat moon pulls her up onto shore? Does she notice? The slow piling of water upon water, inching, gathering, surging up, so that what Fitzgerald called “the great wet barnyard of Long Island Sound” spills over itself?

Even these placid warm waters are part of the great god Ocean, insinuating its fingers around the world. I dive in because I know it, and I like how it feels like on my skin.

What would it take, I wonder, for the ocean to know me? What would I have to be? Ahab? Or 400 ppm?

It’s not a night for storms or strains or hard thinking. Just immersion by silvery light. I took a short swim out to the swimming buoy, spent a moment floating in cool water staring up at the moon, then walked back home.

Look at that green! Surrounding, confining, holding us in. It was beautiful, with the wet lush soggy brilliance that follows two days of violent storms. We’d been thunderstormed out of plans to go kayaking on the mighty Kansas River and had ended up in Clinton State Park, where we wandered around on muddy trails looking for the way down to the lake’s shore. Eileen’s Cole Haan shoes transformed themselves into muddy skis, gliding downhill. In this picture, you can see me and Lowell staring perplexed into the green labyrinth, and Jeffrey sagely consulting the i-Gods.

Since all images are allegories, I think this picture captures the challenge of moving beyond the green, and the aesthetic pleasures of being surrounded.

My first trip to ASLE had something of the disorienting beauty of this woodscape, but also many more simple pleasures. I’ve seldom been to a happier academic gathering, which seems odd given the fairly constant anxiety about eco-crisis. Perhaps it was the infectious high spirits of Serenella Iovino and Serpil Opperman, international eco-thinkers who I met for the first time in Lawrence, or the great food & drink in the fun college town, or finally meeting Stacy Alaimo and Simon Estok and Chris Schaberg, or hearing Cary Wolfe on biopolitics for the second time in a month, or closing yet another set of bars with Lowell, Jeffrey, and Eileen — but in all ways, it was great fun.

On Thursday morning I woke before dawn in coastal Connecticut and somehow made it 1500 miles west to Stacy’s plenary at 10:30 am in the Kansas University Memorial Union. Arguably that place-erasing speed, my pre-dawn itinerary of planes, automobiles, and internal combustion engines, represents an ecological problem. But it was great to get there and think about the eco-poetics Stacy’s finding in submarine depths.

The questions after Stacy’s plenary, which she shared with Cary, were hard to follow. That would become an ASLE pattern. Also a sign of interdisciplinarity?

In a conference filled with questions, I remember the most succinct. At the “Building the Environmental Humanities” roundtable the next morning, it was about the difference between the sciences and the humanities. “They build things, we ask questions.” The panelists didn’t accept that characterization of the “two cultures,” and nether do it. But I do think that there are meaningful distinctions between the sciences and humanities, which make interdisciplinary alliances both productive and challenging. So maybe it’s worth seeking a better way to describe that difference, one that employs a richer understanding of “materiality,” one of the obsessions of at least my strain of this ASLE. We don’t need to flatter the physical sciences by paying homage to direct forces or financial investments, nor conversely to imply that questioning humanists are somehow uncorrupted by modern institutions, economics, and power dynamics. “They” ask lots of questions, and “we” build plenty of things. Might this be a better way to phrase it: “They build models, and we tell stories”? Which perhaps begs the question of what the difference is between testable models and persuasive stories. I’m a narrative-monger myself, though I understand the value of testable models. Perhaps the we/they syntax is too problematic?

I also came away with a perhaps cynical historicizing question: has it ever not been true, at least subjectively true, to say that “Now more than ever…we live in crucial times”? What other times might anyone ever live in? Part of the issue with multiple time scales — human, geological, ecological — remains our difficulty in escaping mortal or perspectival boundedness. Maybe that’s not a problem, more of a condition of embodied thinking, which means that whenever we invoke time scales they are always plural, always adding to what we are already experiencing. Times of the self, the fiction, the scholarly talk, the glacier, the rock, the hummingbird, the river, the thunderstorm…

ASLE was the final lap of the five-part conference relay I’ve been running since late March, and I must say I’m exhausted, ready for a slower-moving summer and the shipwreck project. Conferences are, at their best, productive entanglements, which means (in an eco-sense) that they enable new networks, products, processes. Now it’s time to put those networks to work!

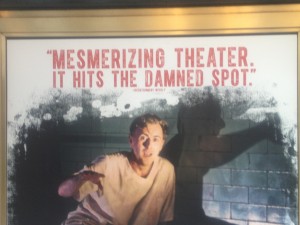

This One-Scot Show was my end-of-semester treat, and this poster gets it right, if hitting the spot means catching you between the eyes. The production interwove an inventive performance by Cumming that only occasionally slipped into caricature — mainly in his whining, petulant child-king Duncan — against a spare institutional backdrop. The performance opened in silence, as a female doctor and husky male orderly medicated Cumming and changed him into a hospital gown. He clutched a paper bag labelled “Evidence” that will eventually reveal a child’s sweater, later appropriated to play the part of Macduff’s doomed son. Concerned faces on the medical personnel implied that the patient might at any time explode, implode, or scatter his bloody fragments about the stage. (But we know that already from Shakespeare.) The first lines spoken were also the first lines in Macbeth, but they worked doubly, referring both to the Weird Sisters and to the institutional trio — patient, doctor, orderly — who are the only figures on stage:

This One-Scot Show was my end-of-semester treat, and this poster gets it right, if hitting the spot means catching you between the eyes. The production interwove an inventive performance by Cumming that only occasionally slipped into caricature — mainly in his whining, petulant child-king Duncan — against a spare institutional backdrop. The performance opened in silence, as a female doctor and husky male orderly medicated Cumming and changed him into a hospital gown. He clutched a paper bag labelled “Evidence” that will eventually reveal a child’s sweater, later appropriated to play the part of Macduff’s doomed son. Concerned faces on the medical personnel implied that the patient might at any time explode, implode, or scatter his bloody fragments about the stage. (But we know that already from Shakespeare.) The first lines spoken were also the first lines in Macbeth, but they worked doubly, referring both to the Weird Sisters and to the institutional trio — patient, doctor, orderly — who are the only figures on stage:

When shall we three meet again?

Some reviewers found the constant shuttling among different characters distracting, and it clearly confused at least a few of the chattering people sitting near me in the theater. There were some over-flashy touches, like the rapid-towel shifting that switched from Lady Macbeth — torso covered — to Macbeth — naked to the waist — but in general Cumming gave an engaging performance and has a great, clear, Scottish voice. The shifts were disorienting enough to draw attention away from some powerful speechs, especially early in the performance, but others took on new force:

Is this a dagger which I see before me?

The backdrop of mental illness made the hero somewhat less than awe-ful in both the ethical and purely theatrical senses. I can’t agree with Ron Rosenbaum that this production provided unique insight into the nature of evil, but by performing the play as a kind of auto-investigation, self-generated therapy or protest against therapeutic invasion, it does show off the paranoid closeness of perhaps Shakespeare’s most hero-centric play. The super-warrior who unseams his enemies from the nave to the chops isn’t much in evidence, but Cumming’s mad, obsessed figure, dragging himself from bed to bathtub to sink, always aware of the overlooking eyes of his attendants and their three video camera-witches, provided menace and danger. He also became, perhaps because he’s the only person to look at much of the time, powerfully sympathetic, in a slightly disjointed, almost Beckettian way.

The backdrop of mental illness made the hero somewhat less than awe-ful in both the ethical and purely theatrical senses. I can’t agree with Ron Rosenbaum that this production provided unique insight into the nature of evil, but by performing the play as a kind of auto-investigation, self-generated therapy or protest against therapeutic invasion, it does show off the paranoid closeness of perhaps Shakespeare’s most hero-centric play. The super-warrior who unseams his enemies from the nave to the chops isn’t much in evidence, but Cumming’s mad, obsessed figure, dragging himself from bed to bathtub to sink, always aware of the overlooking eyes of his attendants and their three video camera-witches, provided menace and danger. He also became, perhaps because he’s the only person to look at much of the time, powerfully sympathetic, in a slightly disjointed, almost Beckettian way.

It will have blood, they say. Blood will have blood.

The most powerful prop on stage was a large doll, dressed in pink, that stood for baby-prince Malcolm, named heir to boy-king Duncan. Without engaging over-much in extra-textual speculations of the sort mocked in the famous essay, “How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth?” I kept thinking that the emotional core of this production wasn’t so much vaulting ambition or shared lust for power but a fundamental rage against the Child and the futurity that children represent. (Does Lee Edelman talk about Macbeth in No Future? He did recently write a great essay on Hamlet.) When the doll gets propped up on the wheelchair-throne for the final tableau, it’s hard not to feel that Macbeth’s death — the conflict with Macduff ends with “him” drowned in the bathtub, where Macduff’s sweater-son had also been immersed — marks the triumph of an infant’s future over an adult’s present.

How does your patient, doctor?

Addressed to the female doctor who has returned to the stage, this line, like the performance’s opening line, works both within the theatrical frame and in Shakespeare’s play. It also edges toward the death of Lady Macbeth, often the emotional high point of the play. The last great Macbeth I saw, by Cheek by Jowl in 2011, had me wanting a production of just the love story, with no one on stage but Him and Her. Cumming’s performance of the marriage was quite strong — he did slightly overdo some of the sexual impersonation jokes when Lady Macbeth read her letter in the bath, and the inventive staging of her seducing her husband into the murder seemed to rely on a sophomoric reading of the line, “Screw your courage to the sticking point.” The central loss or crime or catastrophe in the ambiguous frame story seemed to involve a child, but Lady Macbeth, and the concerned, sympathetic female doctor, were somehow at the heart of it too.

…full of sound and fury, / Signifying…signifying…signifying…nothing.

Certain lines in Shakespeare are too over-familiar to be performed easily. At times Cumming’s soliloquies, in particular, suffered from their clear, direct enunciation: we know the words already, I wanted to say, what else can you do? (Sometimes I think I’m not the intended audience for Shakespeare on Broadway.) Probably the most interesting twist on a canonical phrase was Cumming’s triple-take on what follows sound and fury. He struggled and stopped three times before getting to “nothing,” as if he couldn’t quite get through it, couldn’t quite accept his wife’s off-stage death, his pronouncement of an absurdist universe, the rounding close of the play itself. What comes before nothing?

In the end Cumming’s production stayed, of necessity, within one head. It was propelled by rage of the present against the future, the desire never to cede the stage, not to be displaced —

In the end Cumming’s production stayed, of necessity, within one head. It was propelled by rage of the present against the future, the desire never to cede the stage, not to be displaced —

If it ’twere done, when ’tis done, ’twere well

It were done quickly…

We watched on the video feed as the hero held himself underwater in the bath where young Macduff had been drowned. He couldn’t hold out, and emerged with a splash. Exhausted, avoiding the enthroned doll at center stage, he dragged himself back to his hospital bed. He looked up at the doctor.

When shall we three meet again?

A great performance of the theatrical “now,” packed into a scant 100 minutes. The sun was going down as I left the Barrymore Theater.

(Cross-posted at In the Middle)

When you dive into cold water, it pushes the wind out of you. The icy shock holds you still, just for an instant. You slide beneath the waves into water’s slippery grip, and then lurch back up onto unsteady feet. Now everything’s different. The air bites exposed skin, but it isn’t just the cold or even the wind raking the lake into ragged swells. Something else. Your breath comes in near-frantic wrenches, and you can nearly feel some hidden motions inside your body, some awakened fire, constricted now inside loose ropes of cold. The lakewater has encircled your body, taken you whole – that’s what immersion means – but after you stand up it gradually sloughs itself away. Second by second your breathing reasserts its rhythm. You plunge under a second time, and the cold comes back, but nothing like the first shock.

Early Saturday morning, before my first-ever presentation at Kalamazoo, Lowell Duckert and I went swimming in Lake Michigan. As I usually am, I was seeking meaning. Does it make sense to read frigid immersion as allegory, to say that my scant thirty hours at the Medieval Congress, perhaps five of which were spent sleeping, embody the same impulse as plunging into the cold waters of the Third Coast?

A maiden knight arrives

As an early modernist who’d never been there, I was curious about Kalamazoo. It shouldn’t have been all that exotic – the gap between the periods isn’t that wide, and anyway I’m close to the Sidney and Spenser Kzoo sub-cultures via my first book on romance. Plus the elemental hospitality of the BABEL/ITM/MEMSI/etc flowed through every hour. To paraphrase Jeffrey’s introductory remarks from “The Future We Want,” medievalists and early modernists are better served by seeing each other as alternate sympathies than rival claimants to a pre-modern throne. He sees a chasm between the sub-fields that needs to be bridged, and I’m also tempted to imagine a border across which sorties can sally and trade flourish, but in any case it seems more fun to be on both sides.

Even so, I felt vaguely alien upon arriving at the Congress. The sense that everyone else knew where they were going was part of it. Navigating the foreign WMU campus Friday afternoon to get to my first session seemed Spenserian and allegorical. (Should I say Dantesque instead? Romain de la Rose-like? Spenser is my go-to allegorical marker, but not the only one.) The ground was charged with meanings. The first living creature I encountered on campus was a goose. Symbol of fun? Or the need to extend our circle of attention beyond human actors? Of seasonal migrations? It was raining, and I hadn’t packed an umbrella or raincoat. The first human I recognized was Jeffrey Cohen, driving his rental car slowly down a campus drive. He rolled down his window, spoke my name, smiled, and drove off, leaving me in the rain. Meaning…what, exactly?

During a busy spring of many conferences, I’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between individuality and community. The productive tension between the one and the many has been on my mind for a long time, and thinking back on my trip to Michigan, I have the sense that Kzoo might enable a slightly different response to this endless conundrum. Unlike the annual conferences I regularly go to – SAA, MLA, less often RSA – it’s always in the same place. To my fellow conference goers, many of whom happily rattled off their Kzoo numbers – 12 years straight! 13! 5! 20! – it clearly felt like home.

Like a first-time reader of an over-abundant text, Malory or Dante or Chaucer, I searched for ways into the overwhelming numbers & flavors & ideas on diplay. The goose started things off, and then it wasn’t long before I’d spotted a few grad school friends and eased into the familiar pattern of academic conferences: found the registration table, looped a badge around my neck, arbitrarily narrowed my list of four intriguing sessions down to one.

I ended up choosing what felt like the most Kalamazoo-ish panel, La Belle Compagnie’s “How Shall a Man be Armed?” a live demonstration and modeling of English armoring practices during the Hundred Years War. My BABEL-y and theoretical friends wondered if I was poking fun at medievalism by choosing that panel. And perhaps I was a little, as I retold the story at happy hour, but the truth is I love experiential learning and the pressure living bodies put on ancient structures. I really can’t get enough of that stuff – which is one reason I love teaching with live theater and also why I launched my maritime scholarship by learning to climb the rigging and set the sails on the tall ships at Mystic Seaport back in 2006. The Armor panel was wonderfully dense and awash in technical details, including the influence of Italian and French fashions on English armor designs. (I thought it was good evidence for the claim that modern men’s fashions evolved out of armor.) The panel featured, in the four stalwart men gradually being dressed from foot to helm, a full helping of bodily presence, the force of “now” infiltrating historical expertise. Plus some good jokes, intentional or not: one knight’s beaver kept falling down and interrupting the presenter. It showcased the sometimes awkward fit of scholarly technical precision and fan-boy enjoyment. I could only get to one session as a audience member, but it was a good one.

Fellowship

As at NCS last summer, the communal virtue I wanted to think through at Kzoo was fellowship. I’d done my homework and read a little David Wallace, and I was interested in testing the rough assumption that, compared to my home waters at SAA, Kzoo was more fellowship-full, less hierarchical, more interdisciplinary, and extended across different kinds of intellectual space. That’s a caricature of SAA, but an interesting fantasy about Kzoo.

In many ways, unsurprisingly, the two conferences are more alike than not. I was struck, though here I might be reading from my own private Kzoo, driven by BABEL, MEMSI, etc., by a deep attention to social organization and institutionalization beyond the panels. After seeing men armed, I went from BABEL happy hour -> MEMSI dinner -> BABEL party at Bell’s Brewery. I’ve seldom felt so well taken care of at a conference or so thoroughly awash with fellow-feeling. (At SAA I sometimes consciously shift between different sub-discourses, which I didn’t at all at Kzoo.)

My favorite moments at dinner were watching Jeffrey move from insisting, as drinks were served, that it would be “impossible” to put together another set of MEMSI panels for next year’s Kzoo, because he was out of ideas, to watching him assemble, before dessert, a twenty-speaker mega-panel on “The Impossible.” (My word, supplied by Lowell, is “dry.” Impossible & undesirable, but something we covet and value. Though I now wonder if “memory” has already been taken?)

Bell’s is definitely a place to which I’d like to return. The logistics of the pre-panel swim the next morning trimmed the wind from my sails Fri night, but it’s an excellent spot.

The Cormorant and the Future

The panel I’d come to speak on, “The Future We Want,” dealt out six pairs and a wild card. The 10:00 am time was perfect for a pre-talk lake swim, a quick 60 miles west, before fiddling with flash drives and slideshows.

It was odd that none of the other panelists took up our offer to join us for a dip. Maybe they were waiting in a different hotel lobby at 6 am?

The talks rolled over us like so many cars in a freight train, roaring westbound, peering through fog, monkey at the wheel. I’ll sprint through them in an early modernist spirit of competitive evaluation:

Actually the best part may have been the introductions. Wild-card Jeffrey likened each of us to a different literary genre, then sat in the front row with eyes blazing. Greedy glutton of imagination, lapping it up after lashing us all to the mast!

I see now, but didn’t yet realize as I wrote the talk, that the “various” I was celebrating via Milton’s fallen angel-bird was the difference I’d come to Michigan seeking, the fellowship poured into glasses and spread across campus lawns, the screech of newness in my ears. As usual with acts of discovery, what you find is mostly what you bring. But what I like about new conferences is the slight reshuffling of times and voices, the partially off-balance feeling created by available novelty, and the opening up of new ways.

In maritime historical circles, the idea of the Great Lakes as the Third Coast aims to supplement familiar narratives of “Atlantic history” and Pacific globalization with a different American story, one that enters slightly askew, via the St. Lawrence diagonally out of the northeast. This narrative connects the landlocked center of the continent to a distinctively northern maritime economy, trading furs and timber rather than cotton or sugar. This coast even — quelle horreur! — speaks more French than English, or at least it used to. Adding these fresh-water coastlines to our maritime narratives provides new trajectories for waterborne thinking.

That’s also what I like most about an early spring dip in great waters.

It’ll take me a few days to gather my thoughts about my first-ever trip to Kalamazoo, so as a place-holder, I’ll offer most of my half of the collaborative presentation Lowell Duckert and I did on Sea Change / World change in the GW-MEMSI panel organized by Jeffrey Cohen. The full panel, which brought together six pairs of speakers collectively charged to imagine “The Future We Want,” was as wonderfully mind-bending as anything I’ve encountered since…well, since Alabama, I guess. Except this time compressed into 90 minutes, bewilderingly rapid, and ranging from The Battle of Maldon to multilingual poetics.

These fragments won’t give the full measure of our collaboration, which included daybreak immersion in the icy waters of Lake Michigan and ended (for now) with a public singing of Ariel’s “sea-change.” But if you imagine me as this black-winged bird, you’ll get some of the idea.

In the future I want, I am a cormorant. A screeching sea-crow, I perch on a high branch on the Tree of Life overlooking Paradise, which some call Kalamazoo.

“Various” is the word for what I see. “A happy rural seat of various view” (4.247) is the full line in Paradise Lost, but it’s just “various” that I crave. It’s what I roll around inside my bird’s mouth. Various. All of the things that inhabit this Paradise, spread out before me. Not just one thing, but another.

From my crow’s mouth I scream three horrifying truths:

Truth #1: Change fractures our desire for wholeness. It will break, all of it.

Truth #2: A better name for this planet would be Ocean, not Earth.

Truth #3: Salt water tastes bitter, flavored with the recognition that nothing lasts.

I am high enough up to tree to see Heteronyms.

The term “heteronym” refers to a member of a large group of imaginary personae, numbering over 70, in which the great 20c Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa wrote. These authors, each of whom has an individual name, style, biography, and physical characteristics, collectively represent a rage for variety amid the poverty of identity. Multiple names and multiple selves become ways to navigate our over-abundant world. Author-ness and its auctoritee become various, and the original self appears one of many voices, and not the most important one. The most influential heteronym, Alberto Caeiro, also looks over Paradise. “I don’t pretend to be anything more than the greatest poet in the world,” Cairo claims. “I made the greatest discovery worth making, next to which all other discoveries are games of stupid children. I noticed the Universe.”

My question for our future is, how can we become heteronyms? And my answer is, by looking over the world’s change. Variously.

My crow’s eyes snatch two quick glances out from the Tree of Life over salty vastness.

The first glance finds Bernando Soares, technically a semi-heteronym because of his close resemblance to the biographical Pessoa, and The Book of Disquiet (Livro de Desassossego), his “factless autobiography.” In a fragment that may or may not have been intended for the final work, he writes about human encounters with the ocean:

Shipwrecks? No, I never suffered any. But I have the impression that I shipwrecked all my voyages, and that my salvation lay in interspaces of unconsciousness.

— A Voyage I never Made (III)The whirl of heteronyms teaches shipwreck as identity and salvation, that no voyage arrives without disaster. Therefore we embrace suffering and seek “interspaces.”

And one last wet one, my favorite, Álvaro de Campos, from the “Maritime Ode”:

Wharf blackly reflected in still waters

The bustle on board ships,

O wandering, restless soul of people who live in ships,

Of symbolic people who come and go, and for whom nothing lasts,

For when the ship returns to port

There’s always some change on board!

Campos knows what the sea lures us into accepting. Even music won’t hold us in place.

If my cormorant-self had more time looking out over Paradise with all of you, I’d fly toward medieval heteronyms, Mary Magdalene’s various names and identities in The Golden Legend and Custance’s return to her father in the Man of Law’s Tale.

Can we sing it again, that old anthem? All together?

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea change

Into something rich and strange? (1.2.400-402)