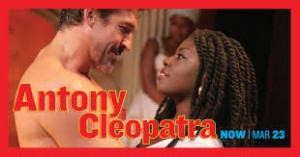

About half a minute into the performance, when Jonathan Cake’s impossibly tall and shirtless Antony strained heavenward while commanding Rome to melt into the Tiber, my eleven-year old daughter Olivia, seeing the play for the first time, whispered to me: “This guy is completely insane.”

About half a minute into the performance, when Jonathan Cake’s impossibly tall and shirtless Antony strained heavenward while commanding Rome to melt into the Tiber, my eleven-year old daughter Olivia, seeing the play for the first time, whispered to me: “This guy is completely insane.”

She loved the show, which calmed down after a frenetic start — but she also had a point. Divine intoxication, giddy love, prophecies, Caribbean music, the loyalties of shrewd underlings from Menas to Enobarbus: the best parts of this production grabbed things and then tossed them aside. “Here is my space!” Antony roared. For this production, the space was Saint-Dominique, 18th century Haiti before the revolution, complete with lovely creole music and a final turn by Enobarbus as voodoo ghost.

With a cast of nine, it was the most intimate Antony & Cleopatra I’ve seen. Roaming around the small space of the Public’s renovated theater, the bi-national cast — four Brits and five Americans, under the direction of McArthur grant wunderkind Tarell Alvin McCraney — worked multiple parts to bring the emotional intensity. Maybe the most engaging element of the show was the four-piece band that played in an upper corner of the stage, including a haunting, repeated version of “Dey” by the 20c Haitian singer Toto Bissainthe. (Click the link and listen!) It’s become standard-issue to stage this play in the British colonial Empire, and dressing the Romans in 18c European costumes wasn’t the freshest move I’ve seen. But I enjoyed the sonic shift to Francophone Haiti, and especially the music.

The most radical changes to the text, beyond the usual assortment of cuts, involved Chukwid Iwuji’s Enobarbus. He opened the play by narrating, from a position in the audience, the famous description of the barge Cleopatra sat in, “like a burnished throne” (2.2.200-27). Throughout the play Enobarbus served as narrator and scene-changer, as well as Rome’s primary Egypt-praiser. Even his death, in which he bemoaned his treachery to Antony until his heart broke, did not stop him from continuing to announce the final scenes as a ghost. He also spoke two major speeches that the play gives to other characters. He appropriated the Roman solider Philo’s opening attack on Antony, “Nay, but this dotage of our general’s / O’erflows the measure” (1.1.1-10), which Enobarbus spoke a little later in the action, after a short scene introducing the lovers. Finally, at the end, Enobarbus grabbed Caesar’s play-closing lines, “No grave on earth shall clip in it / A pair so famous’ (5.2.355-65). These additions to his part seem strange to me: Enobarbus, who not incidentally was the only actor of African descent to play a Roman part, though all the Egyptian-Haitians were dark-skinned, clearly seemed intended to span the cultural divide. When he (as Philo) attacked Antony’s folly just after he (as Enobarbus) had celebrated Cleopatra, I felt the dissonance. I like imagining Enobarbus as the emotional heart of the play, and Iwuji’s performance was charismatic and persuasive. Perhaps he was asked to do too many different things? Or was that the point? That living in and loving both sides of this pre-colonial bi-cultural drama is always too much?

The driving force of this play is always the two lovers, and here I think the Anglo-American cast worked well. Unlike the Bridge Project, which at times seemed an exercise in showing off British strengths and American weaknesses, the combination here of the tall, commanding, English figure of Cake’s Antony against the short, dark, powerfully empathetic first-generation Angolan-American Joaquina Kalukango as Cleopatra was great. At first the height differential was so vast as to seem ludicrous — this Antony could almost look his Cleopatra in the eyes while on his knees before her — but the actors played up each other’s forcefulness. Each was most effective when lamenting the other’s absence: Antony in Rome telling Egyptian tall-tales, and Cleopatra back in Egypt, imagining the “happy horse” that bears the weight of Antony.

Mr Darcy might say of this Antony that he smiled too much, but I think Jonathan Cake’s gorgeous smile — wide, gleaming, inviting — made his performance. Why not have one other gaudy night, he seemed to say? A cure for all his sad captains, Cake’s Antony bounded across the stage, performing rage and botched suicide when necessary, but at his best when smiling.

Joaquina Kulukango’s Cleopatra lacked height, and perhaps political gravitas — the small scale of the production emphasized emotional connections, not realpolitik — but I loved her fast-changing emotional power. Olivia’s favorite scenes involved Cleopatra and the Roman messenger, who was coached in how to describe Antony’s new Roman wife Octavia by an Egyptian character who might be Alexas (as in the text) but was played by the same actor as the Soothsayer and Mardian the eunuch. Why not play along, coached this Egyptian figure, who also sang the Haitian music at other points in the production? Why not just play? The core temptations of this Haitian Egypt were music, water, and volatility.

They lose the world to Caesar, who never smiles and never plays, but really the world always belongs to Caesars. Samuel Collings as Octavius was direct, well-dressed, and narrow in both physical form and in attention. Perhaps his strongest moment came after Antony’s death, when he came onto a stage full of mourners and asked, “Which is the Queen of Egypt?” (5.2.111). He was all focus, no distractions. What difference could it make to him which one was Cleopatra?

The worst cut of the production was the Clown, who never showed up in the final scene. Charmian brought in the asps in water, hold the figs, and I was disappointed because I’d been looking forward to seeing Kulukango’s intense focus directed one last time at a disorderly subject. She hit Cleopatra’s “immortal longings” perfectly: still, haughty, tense as a guitar string. I would have liked to have seen her work harder for release.

Overall, great stuff, especially the music and the two mad leads. Get down to Lafayette St before March 23!