Here’s a link to an essay on mine for Underwater New York’s Waterfronts series, co-published with LA-based magazine Trop.

Here’s a different link to the West Coast version in Trop.

A little splash of the text too —

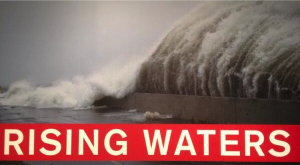

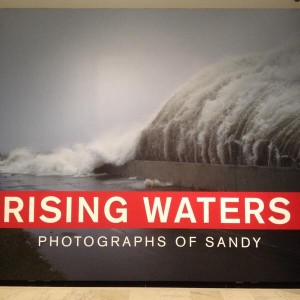

The ocean has many colors. Whenever I look into its blue or green or gray or foaming white face, I think it’s telling a story. It’s remembering something, splashing together lost histories. What does froth murmur?

The Atlantic is childhood.

The Pacific is youth.

I grew up near the Jersey shore and spent many hours walking its uneven sands. That beach is still the landscape through which I read all waterfronts: a gently sloping expanse of gritty beige sand, punctuated by tar-stained wooden jetties that may or may not contain beach erosion. The water is warm in the summer, and the surf rolls on a human scale. Lots of kids start with boogie boards and graduate to surfing, but not me. I never rode the waves any way but on my belly, head down, hands knifing the water in front of me like the prow of a blind boat. If you catch the wave right, it carries you all the way up the beach and leaves you high and dry, face down, eating sand.