Northerly winds and low temps meant a big pile up in Bristol Bay.

Northerly winds and low temps meant a big pile up in Bristol Bay.

All sorts of horrible things invade a teenage girl’s bedroom in Cheek by Jowl’s great new production of John Ford’s incest tragedy, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, currently at BAM.

All sorts of horrible things invade a teenage girl’s bedroom in Cheek by Jowl’s great new production of John Ford’s incest tragedy, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, currently at BAM.

An over-ripe world of corruption and decadence lingers and leers from two backstage doors, but we the audience occupy Annabella’s bedroom for the full duration. A bed with red sheets sits at center stage, making an impromptu altar as well as serving more predictable purposes. Posters on the back wall resemble a pre-digital Facebook page, charting the heroine’s emerging sense of self. True Blood. Kabaret. Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Gone with the Wind. At stage right, apart from the other posters, an image of the Virgin Mary.

The trouble starts when she’s playing sock puppets across the bed with brother Giovanni, and things devolve quickly. As they consummate their mutual love under the red comforter, a group of men, waiting on stage during most of the play, gather round to negotiate the bride’s price. Soranzo, a nobleman who sloughes off the widow Hippolyta in the sub-plot, wins her hand — but the muffled forms under the blanket remind us that bad things are coming.

What I love about Cheek by Jowl is their breakneck packing and headlong intensity. As with last year’s Macbeth, they played straight through without intermission. No place to run, no civilizing cocktails to assert distance between us and them. The strong ensemble cast pushed the metaphors hard — Giovanni drew a lipstick heart on his chest in the first scene, then cut out his sister’s bleeding heart in the last. The chorus of adult men chanted the couple’s lines back to them in an inverted religious rite as they first kissed. Giovanni turns up at his sister’s wedding to Soranzo taking close-up pictures of the bride. The widow Hippolita, played by Suzanne Burden, mocked Annabella’s sexy dancing with disturbing gyrations of her own.

Like Ben Brantley in the Times, I thought Lydia Wilson’s Annabella was the star around which this production rotated, though I like the supporting case more than he does. Annabella, of course, gets the most play, and the most variety: child, sex goddess, coy mistress, penitent, even briefly mother-to-be. In changing she touches everyone else onstage, from his love-idolotrous Byronic brother to her nurse, Putana — the play is full of dark send-ups of Romeo and Juliet, and this Nurse is one of the best — to her finally sympathetic husband, who appears readier to forgive incest and adultery here than in Ford’s script, perhaps because his accusations to his wife after he’s discovered her pre-marriage adultery — “Come, strumpet, famous whore!” — are played, oddly but movingly, as part of a love scene. The kissing stops once he finds out that she’s pregnant.

As in their Macbeth, which Cheek by Jowl transformed into a tale of doomed love, this production ends on a sentimental note. Giovanni, bare-chested as usual, sits on the edge of the bed with Annabella’s bleeding heart in his hand. Their father lies dead beside him, and the Cardinal who in Ford speaks the titular couplet that ends the play (“Of one so young, so rich in nature’s store, / Who could not say, ‘Tis pity she’s a whore?”) mills around with the remaining chorus of men. Rather than giving this corrupt authority his chance to moralize, director Declan Donnellan brings on a ghostly Annabella, dressed in girlish tights and t-shirt instead of the sexy panties and wedding dresses of the previous scenes. She walks silently up to the crying Giovanni and places her hand on his bloody hand, which contains her heart. He doesn’t move or seem to see her — but it’s a tender moment. Pity, I suppose, is what we’re left with.

Here’s a great trailer for a film-in-progress about wooden sloops in the West Indies. Thanks to Dan Brayton for finding this one.

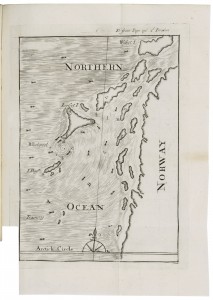

I’m thinking about whirlpools.

Specifically the Maelstrom off the coast of Norway but also whirlpools in general. These fairly regular features of the supposedly featureless ocean arise from the interactions of powerful tidal currents around narrow channels. They’re a bit like tidal bores, which show up in rivers and estuaries and feature in a wonderful scene in Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies.

Here’s an early modern image of the Maelstrom  —

—

I’m wondering if this oceanic feature can partially displace the beach as our primary physical symbol for land-sea interaction?

Whirlpools, like beaches, get formed when the sea & land come crashing towards each other. Both are structured by tide and time, both are fairly predictable, but mathematically complex. Neither was well understood in the early modern period. The downward force of maelstroms, as Poe reminds us, asks us to think of them as descents into the ocean rather than movements towards land. Homer’s whirlpool has a monster inside it.

Thinking of whirlpools or maelstroms as oceanic forms, features that are in their way as typical of land-sea interaction as the beach or other contact zones helps shift us imaginatively off-shore without entirely forsaking land for deep water. The whirlpool is an inhuman and inhospitable place, but it’s still created by land, at least in part. It’s not a human contact zone like a beach or a ship, but it’s a site of interaction.

Despite Poe and Jules Verne, coastal maelstroms aren’t strong enough to suck down ships or submarines. But what if we think of them as windows into the ocean?

These thoughts are all leading up to the Oceanic Shakespeares SAA seminar early next month, where all such questions will be resolved.

We’re only three weeks away from SAA, and I’ve been happily swimming through the flood of papers for my Oceanic Shakespeares seminar. In the next few days I’ll be responding to the authors individually, but I also want to explore a few larger questions and structures that the papers point toward as a whole.

The single largest question the seminar raises for me is the relation between the two terms in its title: what might it mean to connect the vast world ocean to the works, diverse and poly-appropriated though they are, of a single author? I’m hoping that this seminar can help us move past Will-centricity, not only by opening up the vast array of other materials available to salty scholars of this period, from Camoens to Haywood to Joost Von den Vondel and many others, but also by pushing literary culture up against what Whitman calls the “crooked inviting fingers” of the surf. We’ll talk in Boston about how this might happen.

But first, some short introductions / questions for each of the three groups of papers.

Wet Globalism:

These papers have me returning to questions of the sea as cultural contact zone, a space both “free” in Grotius’s sense and also endlessly connected. They also make me wonder about nationalism and inter-European rivalries, remembering that Grotius’s Mare Liberum was itself part of the Dutch struggle against Spain; free seas are not apolitical spaces.

I also recently ran into a few lines from everyone’s favorite Nazi jurist, Carl Schmitt, that captures an Anglophilic vision of the oceanic globe that we Shakespeareans are perhaps more familiar with from John of Gaunt —

The case of England is in itself unique. Its specificity, its incomparable character, has to do with the fact that England underwent the elemental metamorphosis at a moment in history that was altogether unlike any other, and also in a way shared by none of the earlier maritime powers. She truly turned her collective existence seawards and centered it on the sea element. That enabled her to win not only countless wars and naval battles but also something else, and in fact, infinitely more—a revolution. A revolution of sweeping scope, of planetary dimensions. (Schmitt, Land and Sea, Simona Draghici trans.)

I don’t think we need to believe all or even any of that in order to use it to consider the legacy of oceanic English globalism from Shakespeare to Conrad and beyond. But I think it’s worth talking about.

Salty Aesthetics and Theatricality:

This is my sub-section as respondent — Joe Blackmore has Wet Globalism, and Jeffrey Cohen Fresh Water Ecologies — and it’s leading me to my favorite salt-water theorist, Eduoard Glissant, who writes about the sea as a place of “rupture and connection,” and also a “variable continuum” (Poetics of Relation, 151). His vision is also historical; he talks about the slave trade as the defining core of “creolization in the West…the most completely known confrontation between the powers of the written word and the impulses of orality” (6). To live in the post-Columbian West, for Glissant, means inhabiting and traversing oceanic space.

The pressure of maritime exchange and metaphor on aesthetic forms makes up the common subtext of this sub-set of papers. Water proves slippery; it’s hard to pin wetness down, on the Shakespearean stage or in anti-theatrical discourse. I wonder if these papers, and the seminar as a whole, might want to push toward some specific suggestions about the aesthetic force of the oceanic: it’s an agent of change, flowing and shifting, a threat to fixity or rigid conceptions of form, but also — and here I think there’s an interesting counter-current in these papers — something that’s mostly not-quite present, at least not fully. Aesthetic forms dive into the ocean but also surface and leave it. We see wet bodies on stage but not the ocean itself.

Fresh Water Ecologies:

The third group wonderfully focuses our attention back to dramatic particularities — two of the three essays are on Hamlet, which I’m currently teaching — and on the function of fluid spaces in eco-political demarcations. The sea and rivers in these essays comprise ecological and political challenges, with the pirate’s legacy looming large in Denmark. Reading several figures from Shakespeare as deeply watery or maritime — Hamlet, Ophelia, Hotspur — these papers connect watery spaces to human experiences. They make me think, as several other papers do also, about plot and principles of narrative connection. Northrop Frye once joked that in Greek romance, shipwreck was the “primary means of transportation.” What happens when we historicize the plot-ocean of classical romance so that it becomes, very literally, the stage of history?

The oceanic structure of the vortex or coastal whirlpool figures in both of the Hamlet papers, though somewhat differently. I wonder if this recurrent feature, produced by the encounter between mobile ocean and steadfast land, might serve as a metaphor for the disruptive but aesthetically patterned consequences of bringing land and sea together. We often think of this encounter in terms of the beach, which Greg Dening has done so much to turn into a rich metaphor for cultural encounters. Vortices have a different, less friendly aesthetic; they are less human places. We might be able to do something with them.

Great things are happening in Ypsilanti next week! I’ll be in Queens, but wish I could be at Eastern Michigan U for this —

Here’s what Craig Dionne, the host, has to say about it:

“Nonhumans: Ecology, Ethics, Objects.” EMU’s Journal of Narrative Theory (JNT) will sponsor an annual guest lecture focusing on themes currently shaping the humanities, Thursday, March 15, 5-6:30 p.m., Room 310A, Student Center.

This year’s JNT dialogue will focus on posthumanism, specifically its philosophical roots in what is termed the new school of “speculative realism” or “object-oriented ontology.” This is a challenging new paradigm of philosophy in the humanities that defines a generation of ecological theory and practice. Guest speakers include Timothy Morton, professor of English at the University of California-Davis and Jeffrey Cohen, professor of English and the director of the Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute at the George Washington University. Eileen Joy, associate professor of English at Southern Illinois University, will moderate.

I’ve started a page on the blog where I’ll archive audio recordings of my lectures, starting with “A Poetics of Nothing” from last Friday. You can find it under the Pages link on the right hand side of the homepage, or follow the link above.

This is the way the Bridge Project ends: with a star chewing the scenery, not an international ensemble. While past productions in this bi-national Atlantic-spanning series of productions have almost seemed allegories of American and British acting styles, here the big man of stage and screen carried all before him.

He really was great fun to watch. He twisted his body like a ruined athlete, making this a Richard whose martial prowess and physical threat seemed plenty convincing. When crowing to himself alone onstage or working his way through a crowded council table, Spacey was in complete control. The performance wasn’t dazzling, like McKellan’s Lear, or intensely moving, like Jacobi’s. Maybe it’s the impending Super Bowl this weekend — I’m trying to figure out a way to root against both the Giants & the Pats — but I kept thinking I was watching a superstar athlete, someone who makes it look so easy. He was faster, better, stronger than anyone else.

The play doesn’t give much room for co-stars, and with the possible exception of some brief flashes from resisting women — Annabel Scholey’s fiery Anne, Gemma Jones’s wandering Margaret, and later Haydn Gwynne’s Elizabeth (all Brits, btw) — nobody could really play with Richard on this stage. Chuk Iwuji’s Buckingham had a nice turn as a political crowd-pleaser / revival tent speaker when convincing the people to make Richard king, while Spacey’s face was projected onto a large screen on the back of the stage. The close-up of Richard’s expressive face recalled the greater physical intimacy of the camera, and the formal tension between Buckingham’s frantic play downstage and Richard’s subtle, measured acceptance on power on the screen provided a glimpse into what it must be like to work across different media. When Richard came back to the stage, Buckingham lost his ability to match him.

The early scenes, esp the first soliloquy and wooing of Lady Anne, were the highlights, and Howard Overshown’s rendition of Clarence’s dream of drowning had real grandeur and was certainly the best Spacey-less scene. But the production lagged just a bit, and the split-stage rendition of the Richmond / Richard parallel experiences of the night before the battle were a bit predictable. I loved watching Richard wrestle with himself to the very end — “Richard loves Richard, that is, I am I” — and that famous line about the horse allowed Spacey to amp up the volume one last time.

I’ve had some good nights with the Bridge Project since 2009, particularly in their uneven but fun Winter’s Tale with Simon Russell Beale and Rebecca Hall and Stephen Dillane’s brilliant Prospero. I’m not sure I always buy Sam Mendes’s direction, but I’m sorry to see this series of plays past. What’s coming to BAM next winter?

The New Year spirit, plus I must admit a desire to avoid finishing my spring syllabi, led me to my Google Analytics page, and some 2011 Bookfish totals.

It only starts in September 2011, which I guess was when I figured out how to start Google Analytics. But I’m still surprised.