It’s cloudy in Short Beach, so I’m not sure if I’ll bother to assemble my pin-camera. But I’m amazed by the upcoming Transit of Venus, and can’t wait to see astronomical pix. I think I’ll check in via the SLOOH Space Camera once I drop Ian off at soccer practice.

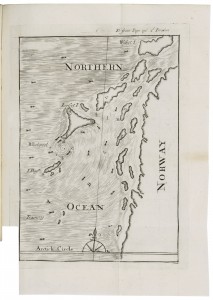

During the 17c, observations of the Transit were a worldwide scientific craze. But we literary types know it best via Mason & Dixon, the pair having made observations of the Transit from the Cape of Good Hope in 1761 and 1769. In the novel, Mason takes the opportunity of the Transit to lecture the lovely ladies of the Vroom family:

‘Ladies, Ladies,’ Mason calls. ‘– You’ve seen her [i.e., Venus] in the Evening Sky, you’ve wish’d upon her, and now for a short time will she be seen in the Day-light, crossing the Disk of the Sun,– and do make a Wish then, if you think it will help. — For Astronomers, who normally work at night, ’twill give us a chance to be up in the Day-time. Thro’ our whole gazing-lives, Venus has been a tiny Dot of Light, going through phases like the Moon, ever against the black face of Eternity. But on the day of this Transit, all shall suddenly reverse, — as she is caught, dark, embodied, solid, against the face of the Sun, — a Goddess descended from light to Matter.’ (92)