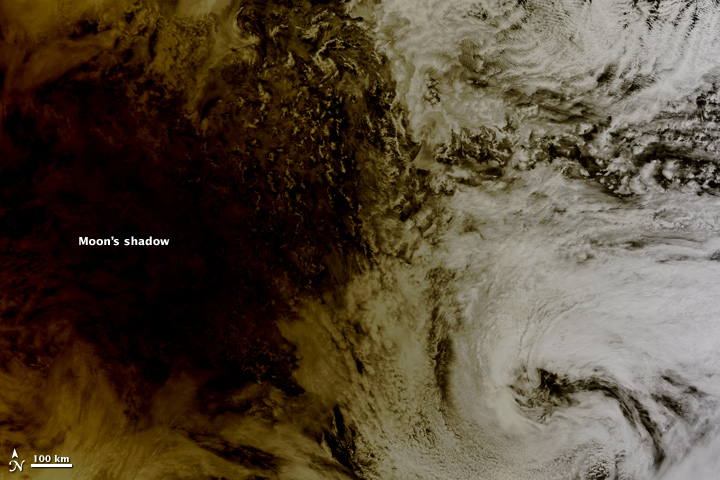

…little time for blogging just now, but this is a great view of the eclipse that we East-coasters couldn’t see last Sunday.

…little time for blogging just now, but this is a great view of the eclipse that we East-coasters couldn’t see last Sunday.

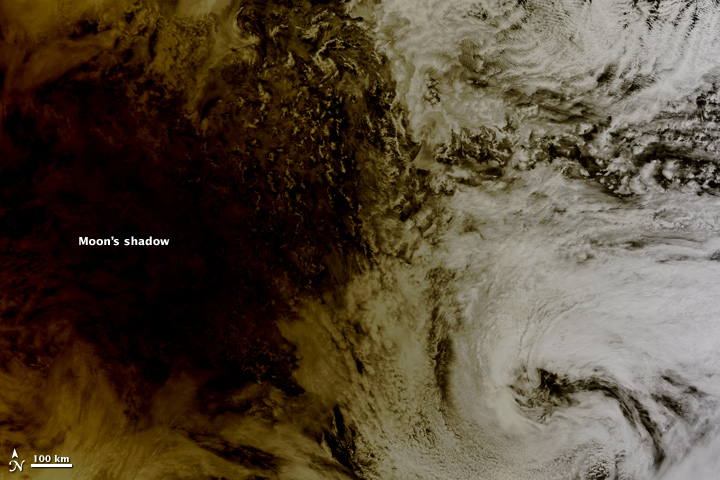

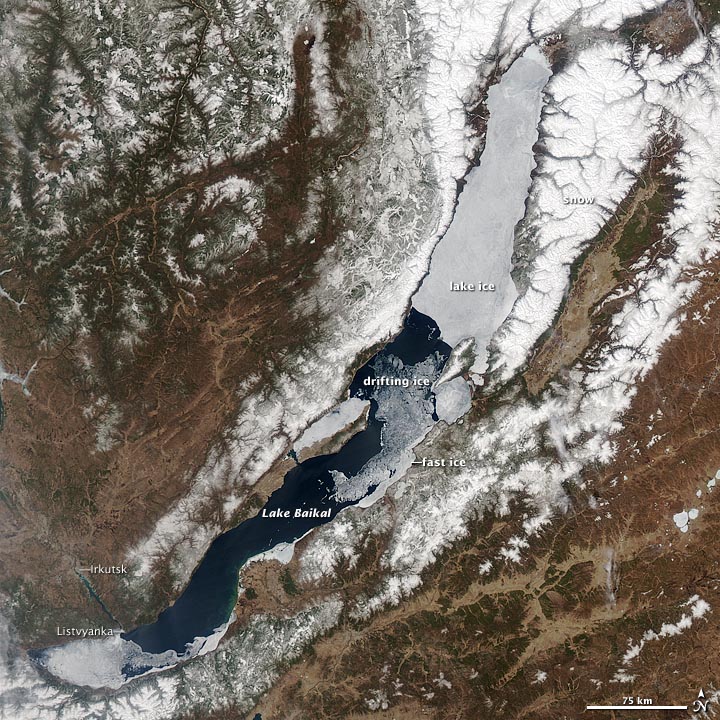

Northerly winds and low temps meant a big pile up in Bristol Bay.

This is the best book on objects I’ve read in a long time. I’m not deeply read in Object-Oriented Ontology (yet), but I think this gorgeous book on garbage has something we all need to listen to. Here’s Rosamond Purcell on books that have decayed almost — but not quite! — past recognition:

There must be some evidence of narrative inside these books. I get to work. The pages are delicate, sealed in clumps, with the hollows between webbed with chitinous shrouds. There is no way to penetrate the pages without destroying them. Inside is a story of organic processes unintended by any author. I peer into these transitional hollows where the elements have been traded — type for ash — and wherever such a translation occurs I search for some visible resolution of decay. I am examining this fulcrum of decrepitude as if it were a thing. Inside these small-scale caves I observe a process of dissolution that is going on, all the time, in the cosmos everywhere — from words to worms to stars. (185)

Owls Head tells the story of Rosamond Purcell’s twenty-year friendship with the junk dealer and eccentric William Buckminster through a series of explorations into Buckminster’s property near Rockland, Maine. The above description takes place in Purcell’s studio, where she’s prying into a shelf full of old books that had been left out in the rain for decades and which became, weathered and slumped together on the shelf, a post-textual artifact. But this kind of object — like all objects, in time? — is always temporary, always in the process not just of becoming some new thing, but also not-becoming — ceasing to be — the thing that it is.

I love the way this book makes us look at discarded things. “Who knew how Roman trash can be?” (116). Sometimes she uses lists, other times photographs in place of footnotes. She tries to give an order to the “bounty” she brings back from Buckminster’s land to her studio outside Boston —

I consider some of the museums that might appear in this room:

Museum of Obsolete Tools

Museum of Wires

Museum of the Croquet and Musket Ball

Museum of Natural Disasters

Museum of Ruined Landscapes

Museum of Failed Attempts

Museum of Filthy MailMuseum of Bisected Objects

Museum of Corrosion (142)

It’s hard sometimes to know what to make of this collection of brilliance and waste. The reader sometimes feels like Purcells’s friend Margary, invited up to Owls Head for some weekend antiquing, in the hope that she will “find something she might like.”

“Wonderful array of frying pans,” she said politely on the first floor of the barn, as I shone a flashlight into the rafters; “terrifying chaos,” she said on the drive home. (122)

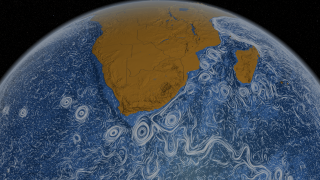

I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

SAA seminars are among my favorite academic events. Pre-circulating the papers, which all seminars do, and exchanging responses beforehand, which most do, means that you come to the event already part of a dynamic exchange, and the trick is to move everything forward. The two hours’ traffic of the seminar needs to make contact with all the distinct projects but not get bogged down by re-hashing material we’ve already covered in our e-exchanges. I used personal introductions, a hand-out, and a parlor game.

When we introduced ourselves around the table I asked, at this risk of bringing sentiment into scholarly life (!), for personal connections to the sea. I’m fascinated by the stories that flowed forth, from paternal stories of the navy to assorted maritime engagements and adventures. I talked about open water swimming. It took a fair amount of time to get all these stories out, more than if we’d just given names & academic homes, but that quick dip into our imaginative oceans primed us to think personally about the academic material that followed.

The parlor game involved me giving each seminar member a maritime term or phrase that has entered common speech — “from stem to stern” “doldrums” “aloof” “the bitter end” — and asking each participant to smuggle that word into our discussions, at which point the word-smuggler would triumphantly cast the printed term into the center of the seminar table. We never got to part two of this exercise, reflecting on how these words might represent or capture the deep interplay of metaphor and technical reality in the way we talk about the sea, but it was great fun. It also helped us make transitions, which can be awkward at these things. I used my phrase, “back and fill,” to shift us out of autobiographical maritime reflections and into Carl Schmitt’s Anglo-centric vision of maritime empire.

The seminar outline offered to a few general questions — Schmitt and empire, Glissant and the beach, an assortment of oppositions including metis/intellect, beach/whirlpool, and surface/depth — to get ideas circulating without tying them too explicitly to specific papers. We concluded, perhaps too easily, that we don’t like neat oppositions, though I also wonder if the desire to connect or blur oppositions isn’t in its own way as oversimplifying as the binaries themselves. The trick may be finding a way to think meaningfullly about difference and connection at the same time.

My job when navigating the 13 great papers and fantastic contributions of two non-Shakespearean respondents was keeping us off rocky shores, so my notes on the seminar outline aren’t terribly coherent. Some great stuff about cultural differences across different ocean basins, esp the Med / Atlantic / Pacific, and also the fresh/salt/estuary relationship — what to call it? A binary plus one? One interesting thing about estuaries is that their salinity changes with the tide and also with wind and weather, so they are perfect places to interrogate the fresh/salt distinction. There’s a way, as I was thinking some time ago, that this distinction maps onto local/global concerns: all fresh water questions are basically local, while salt water circulates globally.

The question of Shakespeare as such, interestingly and perhaps reveallingly, never really came up. Plenty of papers took up non-Shax-y topics and authors, and several seminarians used Shakespeare as a stalking horse for big questions about theatricality or ecology or the historical changes that accompany early modernity. Jeffrey Cohen hid his Bard-o-skepticism until he wrote his blog posts, where he has generous things to say about the whole event.

After the seminar, the rest of SAA was a blur of bars & plenaries, not always in that order. I very much liked the primatology panel with Holly Dugan & Scott Maisano, and thought the Fri morning plenaries were a bit bland in their admiration of all things SAA. Or perhaps I’m just no longer used to closing the bar, which makes me a bit cranky at a 9 am lecture!

I’m especially grateful to my two guest-interlopers, Jeffrey Cohen and Joe Blackmore, whose contributions did what I’d hoped they would do, stretching our discussion chronologically and linguistically and imaginatively. All academic conferences, even international ones like SAA, tend toward in-group parochialism, esp when our shared subject so often gets claimed as “not of an age, but for all time.” The idea of the seminar was not really to substitute “ocean” for “Shakespeare” in an all-embracing way, but to seek out fluid metaphorics — flows instead of spaces — that might enable us to deal with vastness and distance in different ways.

So — a new big thing for Oceanic Shakespeares? I’m not sure yet. But certainly wide horizons and strong winds blowing.

Pretty gorgeous shapes caused by off-shore ice flows. Makes me think of the article in yesterday’s Times about the theory that unusual tidal flows put that iceberg in front of the big ship in 1912.

Next week in Buzzard’s Bay!

This tender love story between man and corporation won’t break your heart — we all know what happens when the company relocates to Mars, where office space is cheap — but the show gets down inside you and does its work. It’s as sharp and funny a take on today as you’re likely to find. If you’re in New York this weekend, get to Joe’s Pub to see it. The Times likes it too.

This tender love story between man and corporation won’t break your heart — we all know what happens when the company relocates to Mars, where office space is cheap — but the show gets down inside you and does its work. It’s as sharp and funny a take on today as you’re likely to find. If you’re in New York this weekend, get to Joe’s Pub to see it. The Times likes it too.

Bandleader / playwright Ethan Lipton sings the small joys of the workplace — “I’ve got a place to go in the morning” — and unfurls the half-noticed pleasures of that temporary community, with its private languages — “information refining” — and particular characters, including a special vocal appearance by “the last sandwich in the conference room.” He loves the place, but doesn’t want to leave Our Town.

(Side note #1: I’m blogging from Mars right now, on a sunny spring morning. I commute from here to the outskirts of Our Town in pre-dawn dimness, but I’ve come to like Mars. It’s not as dry as you might think.)

He tells us that his master plan is a life in which there’s “time to make up stories while also eating,” and this brilliant, funny show performs in the wide gulf between economic reality and artistic imagination. The fantasies keep on coming. “When we move in with my aging middle-class parents” leads to “I’m gonna incorporate,” a nostalgic lefty hymn, “Did you hear what they did at the WPA?” — even artists, this song tells us, have to eat — and then the title song, “No Place to Go.”

My favorite parts evoke the NYC office culture I’ve not worked in since I left Random House back in ’92. The dark guttural of the last sandwich in the conference room growls, “Somebody wants me!” The center fullback of the soccer team keeps everyone organized. “Do they still make men in Brooklyn?” asks a strong sentimental ballad.

(Side note #2: The competitive spirit in the soccer song made me think back to the last time I saw Ethan Lipton in person, playing ultimate frisbee at UCLA with the Buffalo Nights gang. I remember he was pissed at me for not throwing the disk his way.)

The closer was “Nothing but a comeback in my wallet,” with supporting vocals from the brilliant three-piece “orchestra,” the highlight of which, from where I was sitting anyway, was Vito Dieterle’s gorgeous saxophone.

We might not be able to believe that saxophones and songs can break corporate power. But somewhere above Oklahoma, Woody Guthrie smiles down on this one.

Again, if you’re in New York this weekend, get thee to Joe’s Pub.

When I saw the cover-page review in the Times Book Review, this seemed an obvious novel to read just before “Oceanic Shakespeares.” It’s a sailing and prep-school story, and while I don’t always love the latter, the sailing-language in this book is fresh and precise:

When I saw the cover-page review in the Times Book Review, this seemed an obvious novel to read just before “Oceanic Shakespeares.” It’s a sailing and prep-school story, and while I don’t always love the latter, the sailing-language in this book is fresh and precise:

You never sail with one wind. Always with three. The true, the created, and the apparent wind: the father, son, and Holy Ghost. The true wind is the one that can’t be trusted. The true wind comes in strong from one direction, but then the boat cuts through the air and creates her own headwind in turn. (39)

The plot, in a way that may be so familiar it goes unremarked in in the two reviews I’ve read, limns The Tempest. Our hero is Jason Prosper, master-sailor, wind-seer, and young man with a dark past. His sailing partner & best friend Cal — surely we don’t need to spell out the remaining syllables? — has committed suicide, which leads Prosper to a new school, where he finds Aidan — the name means fire, not air, but it seems close enough — a magical California spirit. A familiar trio.

The best parts press hard against the metaphorics of sailing. Jason almost drowns his prospective new partner on the first practice of the season, quits the team for the fall, then returns in spring. That plot seems rote enough, but the book’s more interested in connections —

Knots are a form of control. The halyards, sheets, painter, and lines all run because of knots…. ‘The funny thin about a knot,’ [Jason] said, ‘is that it actually weakens the rope.’ (168).

When I read the Times review I wanted to play the etymology game that the author made me wait til almost the very end of the book to find:

We’d see who could come up with the most common words, sayings, and cliches that came from sailing. ” Batten down the hatches,” “give a wide berth,” taken aback,” “above-board,” “true blue,” “high and dry,” “hand over fist,” “know the ropes,” three sheets to the wind,” “walk the plank,” “catch my drift,” “on an even keel,” “loose cannon,” “miss the boat,” “chew the fat,” “let the cat out of the bag,” “no room to swing a cat,” “beat a dead horse,” “shake a leg,” “slush fund,” “cut and run,” “close quarters,” “deep six,” “scuttlebutt,” “chockablock,” “the cut of your jib”… (273)

The title comes from a term Cal invents to fill out this list —

…it means the right sea, the true sea, or like finding the best path in life. It’s deep. I’m telling you, it’s going to catch on. By this time next year, everyone will be using it. (274)

As that last quotation shows, this debut novel risks sentimentality, in the way that writing about near-children sometimes lets you get away with. (It reminds me a bit of The Hunger Games, another first-person teen novel that really has caught on.) Or is it writing about sailing that enables sentimentality? That deep sea of feeling?

All sorts of horrible things invade a teenage girl’s bedroom in Cheek by Jowl’s great new production of John Ford’s incest tragedy, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, currently at BAM.

All sorts of horrible things invade a teenage girl’s bedroom in Cheek by Jowl’s great new production of John Ford’s incest tragedy, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, currently at BAM.

An over-ripe world of corruption and decadence lingers and leers from two backstage doors, but we the audience occupy Annabella’s bedroom for the full duration. A bed with red sheets sits at center stage, making an impromptu altar as well as serving more predictable purposes. Posters on the back wall resemble a pre-digital Facebook page, charting the heroine’s emerging sense of self. True Blood. Kabaret. Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Gone with the Wind. At stage right, apart from the other posters, an image of the Virgin Mary.

The trouble starts when she’s playing sock puppets across the bed with brother Giovanni, and things devolve quickly. As they consummate their mutual love under the red comforter, a group of men, waiting on stage during most of the play, gather round to negotiate the bride’s price. Soranzo, a nobleman who sloughes off the widow Hippolyta in the sub-plot, wins her hand — but the muffled forms under the blanket remind us that bad things are coming.

What I love about Cheek by Jowl is their breakneck packing and headlong intensity. As with last year’s Macbeth, they played straight through without intermission. No place to run, no civilizing cocktails to assert distance between us and them. The strong ensemble cast pushed the metaphors hard — Giovanni drew a lipstick heart on his chest in the first scene, then cut out his sister’s bleeding heart in the last. The chorus of adult men chanted the couple’s lines back to them in an inverted religious rite as they first kissed. Giovanni turns up at his sister’s wedding to Soranzo taking close-up pictures of the bride. The widow Hippolita, played by Suzanne Burden, mocked Annabella’s sexy dancing with disturbing gyrations of her own.

Like Ben Brantley in the Times, I thought Lydia Wilson’s Annabella was the star around which this production rotated, though I like the supporting case more than he does. Annabella, of course, gets the most play, and the most variety: child, sex goddess, coy mistress, penitent, even briefly mother-to-be. In changing she touches everyone else onstage, from his love-idolotrous Byronic brother to her nurse, Putana — the play is full of dark send-ups of Romeo and Juliet, and this Nurse is one of the best — to her finally sympathetic husband, who appears readier to forgive incest and adultery here than in Ford’s script, perhaps because his accusations to his wife after he’s discovered her pre-marriage adultery — “Come, strumpet, famous whore!” — are played, oddly but movingly, as part of a love scene. The kissing stops once he finds out that she’s pregnant.

As in their Macbeth, which Cheek by Jowl transformed into a tale of doomed love, this production ends on a sentimental note. Giovanni, bare-chested as usual, sits on the edge of the bed with Annabella’s bleeding heart in his hand. Their father lies dead beside him, and the Cardinal who in Ford speaks the titular couplet that ends the play (“Of one so young, so rich in nature’s store, / Who could not say, ‘Tis pity she’s a whore?”) mills around with the remaining chorus of men. Rather than giving this corrupt authority his chance to moralize, director Declan Donnellan brings on a ghostly Annabella, dressed in girlish tights and t-shirt instead of the sexy panties and wedding dresses of the previous scenes. She walks silently up to the crying Giovanni and places her hand on his bloody hand, which contains her heart. He doesn’t move or seem to see her — but it’s a tender moment. Pity, I suppose, is what we’re left with.