The best literature is always a take: there is an implicit risk in its execution, a margin of danger that is the pleasure of the flight, of the love, carrying with it a tangible loss but also a total engagement that, on another level, lends the theater its unparalleled imperfection faced with the perfection of film.

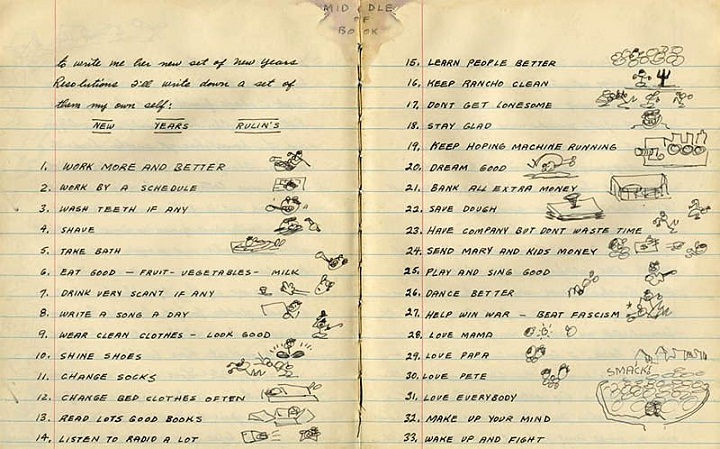

Three Rulin’s for 2012

Abbreviating the spirit of Woody, I’ve got three things this year: write, cook, and swim.

The first — “Work more and better” — wants a renewed focus on prose style. When I wrote At the Bottom of Shakespeare’s Ocean in 2009, playing with my academic style meant no footnotes, prose-poem interludes, a half-dozen different ways of interpolating modern writers from Melville to Walcott to Glissant, and working through sentences every day in the warm waters of Long Island Sound. In 2010, writing case labels and brochures and website text for “Lost at Sea: The Ocean in the English Imagination, 1550 – 1750” meant writing for a new audience: clear, brief, lucid prose, plus more imaginative moments in two talks in the theatre. This past year had me writing for various outlets — a couple journals, introductions for two essay collections, the still-looming shipwreck book — and trying to figure out how much of the churn and froth of Shakespeare’s Ocean I can keep as I return to footnote-landia. In 2012, the answer will be: all of it, and more. It’ll be fun.

Second — “Eat good — fruit — vegetables” –digs into cooking and eating. No farmer’s markets here in CT during the winter, but replacing Stop’n’Shop with Bishop’s Orchard helps a lot. Though I think our wine won’t come from CT…

Last — “Keep hoping machine running” — I want to build on 2011’s rediscovery of swim racing, which took me to Bermuda for a 10km open water race in October. It’s great to have an athletic focus that doesn’t pound my lower body — though I’d also like to keep running on days I can’t get to the pool. Not sure what the long swims will be in 2012: I’m waiting to hear about the Chesapeake Bay Swim, the lottery for which gets decided in a few days. There are also a few fun NYC swims, including two in the Hudson and two in the Bay. The Little Red Lighthouse is a current-assisted 10km in September that looks like fun. The Hellespont looms, but not in 2012.

I’m also considering some races in the pool, for the first time since the mid-80s.

A good line-up of academic events too, including chairing seminars at the SAA in Boston and the ISA in Stratford, giving a “Coastal Perspectives” Lecture at UConn Avery Point and a talk at CUNY, plus heading west and slightly out of field for the New Chaucer Society in Portland in July. The big family trip to Europe will follow the Stratford conference, though we’re still working out the details. France or Greece?

Woody’s New Years Rulin’s

Iberia by Night

From the International Space Station

From the International Space Station

Sand Sea

In southwestern Libya, near the borders of Algeria and Niger, lies a sand sea known as Idhan Murzuq (also Sahra Marzuq) that rarely receives water from either sky or land. The extreme desert’s complex dunes are shaped by dry winds. But extending from the northeast quarter, a corridor of sand lines what used to be a river channel: Wadi Barjuj.

— from NASA’s Earth Observatory

“Half-fish, half-flesh”: The Poetics of Dolphins

I’m reading copy proofs today for a forthcoming article on dolphins in the early modern imagination. It’ll be out fairly soon in The Indistinct Human, a great-looking collection edited by Jean Feerick and Vin Nardizzi. I have some fun with Thomas Browne, Shakespeare, Lucian, Ovid, William Diaper, Thomas Pynchon, and a few others.

I’m reading copy proofs today for a forthcoming article on dolphins in the early modern imagination. It’ll be out fairly soon in The Indistinct Human, a great-looking collection edited by Jean Feerick and Vin Nardizzi. I have some fun with Thomas Browne, Shakespeare, Lucian, Ovid, William Diaper, Thomas Pynchon, and a few others.

My favorite part was digging into the classical origin story, in which the first dolphins had been human pirates, transformed by the child-god Bacchus after they seemed ready to kidnap him. Pirates and dolphins, with their frightening or happy faces, present inverse visions of the mammal-ocean relationship.

I also enjoyed writing the Mason & Dixon part —

To draw out the contemporary relevance of this human-dolphin hybrid, I’ll introduce each of the five remaining sections with an excerpt from a much more recent literary vision of humanity living intimately with the ocean, Thomas Pynchon’s postmodern historical novel, Mason & Dixon (1997). My point in directing attention to an episode in the novel in which the eponymous cartographers inscribe a Line across the Atlantic where they eventually settle in quasi-oceanic space is to show how enticing and problematic the human-ocean boundary remains. This episode of Mason & Dixon presents a postmodern literary iteration of the basic human desire to engage oceanic space that underwrites early modern representations of dolphins. Pynchon’s novel uses imagined technology, rather than mammalian bodies, to create its utopian solution, but Pynchon’s portrayal of human life in direct, transformative contact with the deep reveals the continuing urgency of the fantasy dolphins represented in the early modern period and before. In conclusion I shall bring Pynchon’s ocean-crossing Line together with early modern dolphin-humans to speculate about the changing relationship between technological utopianism and natural difference in visions of maritime humanity.

Still harping on that Aquaman Fantasy…

Titus at PublicLab

An intense, high-spirited night last night at the Public. Michael Sexton’s production of “Titus” was bloody bloody and lots of fun. They really nailed the play’s strange combination of hyper-melodrama and almost-playfulness, leading up to an over-the-top finale at the final banquet, complete with (actual) buckets of blood, cartoon post-it notes, and a food-fight between Titus and Tamora with mushy pieces of pie.

In the chaos, Titus’s recipe almost sounded simple, a straightforward and literal way of making sense out of disorder —

Let me grind their bones to powder small,

And with this hateful liquor temper it,

And in that paste let their vile heads be bak’d. (5.2.197-200)

Several performances stood out in a strong cast. Jacob Fishel as Saturninus and Jennifer Ikeda as Lavina were both veterans of Red Bull’s brilliant Women beware Women in 2009, a production that gets better each time I remember it. (I think about the old joke about Juan Rulfo, author of Pedro Paramo, whose reputation supposedly grew with each new novel he didn’t write.) Fishe’ls fey Saturninus made me want a bigger part for him next time. Ikeda’s mute presence during Marcus’s interminable Ovidian lament upon discovering her maimed (“Alas, a crimson river of warm blood, / Like to a bubbling fountain…” 2.4.11-57) made a devastating critique of poetic fancies.

Ron Cephas Jones, who I thought did a decidedly mixed job as Caliban and Charles the wrestler in the Bridge Project’s As You Like It / Tempest double bill a few years ago, was a great Aaron: smart, sexy, charismatic , and powerful. Strung up by Lucius and awaiting execution, he rained brags down on his captors’ heads —

Even now I curse the day — and yet I think

Few come within compass of my curse —

Wherein I did not do some notorious ill… (5.1.125-7)

Rob Campbell’s Lucius and Stephanie Roth Haberle’s Tamora were also strong, but I’m ambivalent about Jay O. Sanders as Titus. He’s big and imposing, with a bear-ish presence that filled up the stage in army camo during the first scene — but too often, esp in the opening parts of the play, his bear was more teddy than grizzly. He hit his stride after losing his mind, and in some ways the part felt more Lear-like and aged than I might have liked. He made a compelling mad father, but less of a conquering general. “I am the sea,” he claims when trumpeting his grief — but he didn’t quite get there, at least not for me. The bad guys — Aaron, Saturninus, Tamora — had the flash in this production.

The lab-budget staging was great: a stack of maybe 3 dozen 8 x 4 plyboard sheets were moved, illustrated, and shuffled around to create almost everything — late in the action they were tables, kitchen counters, and an executioner’s board, earlier they had been thrones and gravestones and pits and caves. I especially loved watching Frank Dolce, who played the boys’ parts, draw symbolic cartoons — birds, crowns, swords — on wood and on post-it notes, and Lavina’s mouth-held drawings in act 5 extended this conceit.

I also had the strange experience of slightly mis-hearing Aaron’s line about surprising Lavinia in the woods — I heard “The woods are roofless, dreadful, deaf, and dull,” but the line reads “ruthless” — and thinking Robert Frost. Not sure what to make of that.

Humanities Research and “Impact”

My old grad school buddy John Staines sent me to this Chronicle article via Facebook. The very short summary is that, at least according to Google Scholar and some other quickly-formed citational studies, not all of our humanities articles and books are widely read, cited, or otherwise influential in ongoing scholarship or the wider public. Surprised, are we?

There are lots of problems with this study: Google Scholar does not really do what this author wants it to do; the ten-year window might be too short to get a good read on impact, given the glacial publication cycle is in the humanities; and the breakthrough rate observed — maybe 1 book out of 10 showed a sizable spike in citations? — does not seem all that bad, esp when compared with comparable industries like commercial book publishing, in which 10% of the titles generate 100% of the profit, or film & TV, which I think operate under a similar model.

I also doubt the core claim: that pressure to publish quickly and abundantly makes us all “worse teachers and colleagues.” The article provides no real evidence on this point, just suggestions that junior faculty suffer under “publish or perish” and anecdotes about shutting the office door in a curious student’s face because the professor needs to keep working on the book. I don’t question the anxiety, but I doubt the bleakness of this scenario. Do most assistant professors seem to their students or colleagues to be “nervous, isolated beings who end up regarding an inquisitive student in office hours as an infringement”? Not in my department. It seems just as likely that publishing makes all of us better teachers and colleagues: better writers, more ambitious thinkers, and more widely knowledgeable in our own and cognate fields.

But even as I don’t think this article has its facts or interpretations right, I do think there’s a problem lurking in those weeds. We humanities scholars work very hard creating the products of our research, which mostly means writing articles and books, and in some cases also building web-interfaces or curating exhibitions or similar things. But when the thing is in print we mostly stop working on it. We mostly don’t think it’s our jobs to make sure that the work gets into wider circulation: we off-shore that job to journals and presses, which mostly don’t have strong publicity departments anymore, even if they once did. Maybe what we need isn’t less scholarship, or even better scholarship, but better press.

(Parenthetically, I also wonder if this article is adapting the “impact” requirement in the UK’s Research Assessment Exercise, which especially values notices of scholarly work in the popular press or other non-scholarly media.)

So my question is — what would happen if we decided to take on more explicitly this job of publicity and outreach? What if we valued it and rewarded it, so that our intellectual task is not done when the book appears in print, but continues, and getting its core ideas or findings to different audiences is part of the program? What if, rather than outsourcing publicity to the shrinking staff of University Presses, we started to think of it as something we do ourselves, through partnerships internal and external to university cultures?

To some extent we already do this, by giving talks at conferences and academic events big and small, by sharing bibliographies, by formal and informal intellectual exchanges. The growth of Facebook and academic blogs has presumably expanded the reach of this practice: I wonder how hard it would be to prove that FB sharing increases academic book sales or future citations? Not very hard, I imagine.

One model for my thinking about this sort of thing is the medievalist conglomerates that circle around the In the Middle blog and the BABEL Working group — Eileen Joy, Jeffrey Cohen, Karl Steel, lots of others. Plus a few other academics whose work I’ve encountered mainly via the web: Graham Harman, Tim Morton, Sarah Werner, a few others. I’d bet — though I’m not sure how I’d go about proving it — that all these people’s work has more “impact” b/c of their web outreach. Self-promotion, I suppose — oh, the horror! — but it’s promotion in the form of engagement and intellectual exchange, which is more fun than just mailing flyers or postcards.

Eileen, a co-founder of BABEL & co-editor of two open sources publishing projects, punctum books and O-Zone, is really visionary in this area. What I like most about her thinking on this topic is that she does not assume that open source means cost-free; she asks us to build private and public associations with various institutions — not just universities, but also libraries, museums, civic groups, etc — interested in and willing to pay at least something to support ideas and exchange. See her bracing set of comments about open access publishing back in October.

As she says —

We’re smart, creative people. We can do this. We can look at and even grasp and remold the bigger picture, and we do it not just for ourselves, but in order to create the spaces and breathing-room and necessary *outlets* for the greatest amount of production possible of the greatest number of ideas. There is no more virtuous work in my mind in the academy at present, and it isn’t free.

Early Modern Theatricality at Rutgers

I caught the last half of a lively two-day conference at Rutgers last Friday. Early Modern Theatricality in the 21st Century, organized by Henry Turner, brought an international crew together to put pressure on “theatricality.” The organizing gambit was 10-minute papers and one-word titles, from “now” (Scott Maisano) to “formactions” (Simon Palfrey) to “festivity” (Erika Lim) and “indecorum” (Ellen MacKay), plus a few dozen others. I missed the early sessions, at which Henry seems to have entertained the crowd with multiple dramatic readings of the conference’s one-paragraph blurb, but caught the last 13 speakers in 2 sessions.

I caught the last half of a lively two-day conference at Rutgers last Friday. Early Modern Theatricality in the 21st Century, organized by Henry Turner, brought an international crew together to put pressure on “theatricality.” The organizing gambit was 10-minute papers and one-word titles, from “now” (Scott Maisano) to “formactions” (Simon Palfrey) to “festivity” (Erika Lim) and “indecorum” (Ellen MacKay), plus a few dozen others. I missed the early sessions, at which Henry seems to have entertained the crowd with multiple dramatic readings of the conference’s one-paragraph blurb, but caught the last 13 speakers in 2 sessions.

A couple things struck me. Most of all was the concentrated effort to expand theatricality’s range, to move this concept away from familiar haunts. I missed Peter Womack’s “Offstage,” but many of the talks gestured beyond the wooden O to street festivals or Parliament or philosophy. Even when we stayed on or near the stage, we often lurked at the margins, or at the borders between players and audience.

The presentations also collectively showed how little current criticism defines early modern drama as consubstantial with Shakespeare. Will made some appearances, but his plays were part of a group and a broad culture of theatrical practice. Perhaps the signature moment of this tendency came when Mike Witmore semi-apologized for drawing all the examples in his talk about “eventuality” from the final moments of Shakespeare’s romances, “because of where I work.”

Some familiar border skirmishes between history and literary habits showed themselves in a cluster of talks by Peter Lake (“Import”), Chris Kyle (“Parliament”) and Blair Hoxby (“Passions”), but in general the anachronism police were not in evidence. Everyone seemed happy to think in divided chronologies, standing astride the 21st and 16th-17th centuries. “Theatricality,” of course, is abstract enough to draw from both periods, w/o the special difficulties of a 19c term such as “ecology.”

I was left mulling about limits and senses of ending. One of the things I love about going to the theater is that it ends, the curtain closes, and we get to go home. If we invest our critical energies in pushing theatricality offstage, might we risk attenuating the pleasures of closure? Where might theatricality end? There is a significant performative aspect to all human interactions, but might the difference between theatricality and performativity be that theatricality is a sub-set, a special case in which a certain space and time gets marked off as different, temporary, luminous? I’m tempted to think so.

We ran out of time before I could ask whatever half-phrased version of that question I was trying to squeeze in, but Scott Maisano’s conference-ending comment also pointed toward the limit or borders of the theatrical transaction. Scott observed that Britomart’s ordeal in the House of Busirane (FQ III.12) contains virtually all the features of theatricality the conference had raised — but, as Scott did not polemically conclude, can a poetic epic really be theatrical? Mike Witmore had also framed his talk by describing the pleasurable and bewildering experience of teaching Heliodorus to undergrads — but when I chatted with him about that at the break, he suggested that the scene in the Ethiopian court was an ekphrasis of the theater, & thus, perhaps, about theatricality even if not presented on stage.

Clearly both Spenser and Heliodorus are thinking hard about theatricality– but surely these moments are not theatrical is the same sense as The Winter’s Tale or the Shoemaker’s Holiday or a Lord Mayor’s show or even a session of Parliament? Don’t we need at least two real human bodies in a particular shared space and time to have theatricality?

Poetic epics and prose romances can be theatrical, or meta-theatrical, or engage in a critique of theatricality. But I suspect that it might be worth drawing a distinction between a performative enactment in an at least partially marked-off time and space, and a textual product like a poem or a prose fiction. There are lots kinds of of overlap and exchanges between page and stage, and artifacts like a film or a digital audio file might blur these lines, since they are artifacts that contain traces of “real” bodies. The long tradition of oral recitation as a primary means of transmitting prose texts — the “fair ladies” in Sidney’s Arcadia — also pushes these two modes together. But bodies and words still might be distinguishable from words alone.

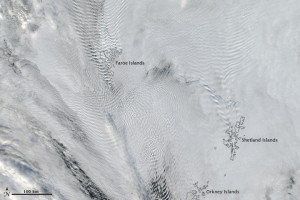

Clouds over the North Sea

“If air were visible, it would be a thing of mesmerizing beauty and motion.” So says NASA.

“If air were visible, it would be a thing of mesmerizing beauty and motion.” So says NASA.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- …

- 70

- Next Page »