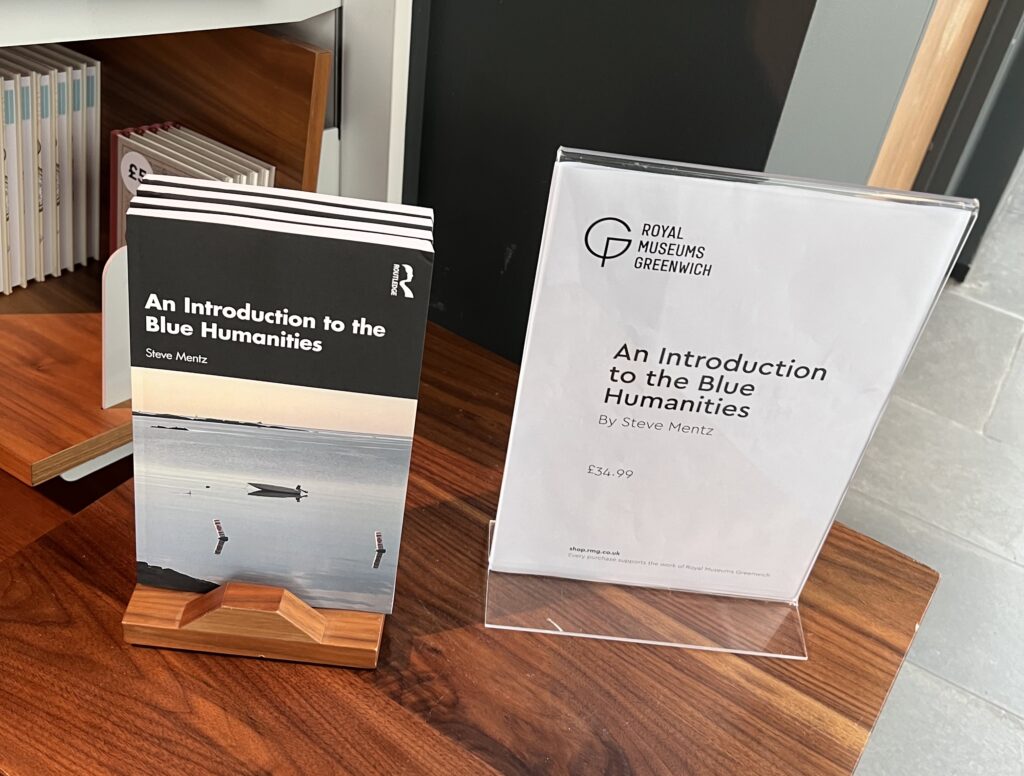

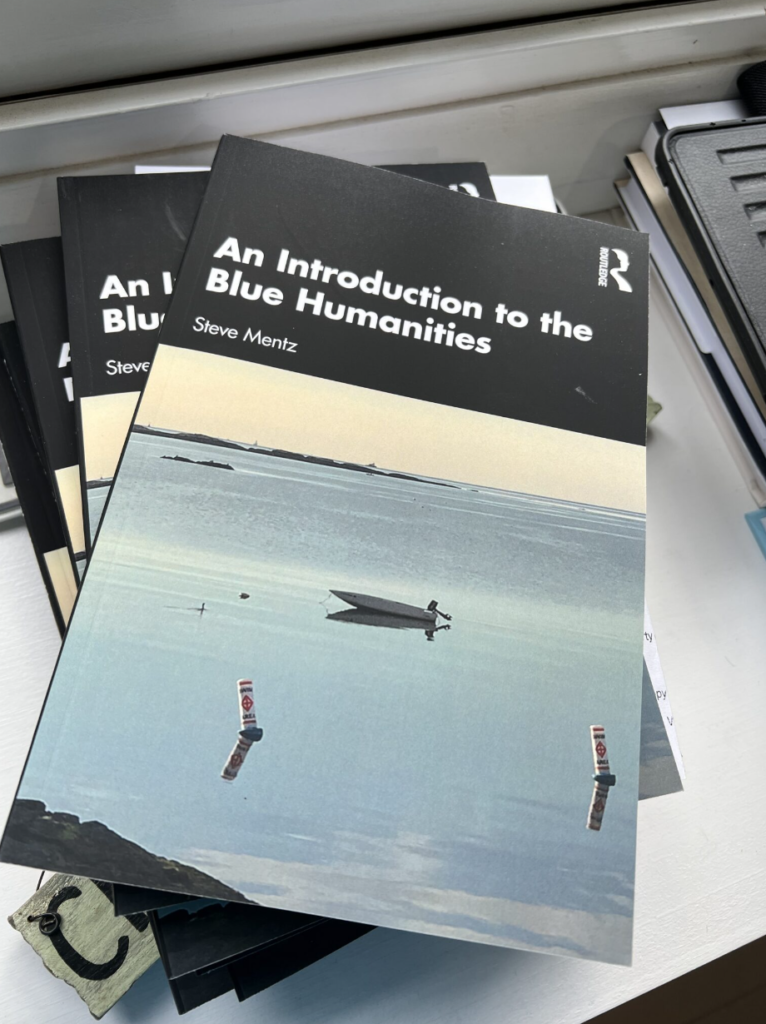

The big event of the year for me came early, when An Introduction to the Blue Humanities came out in July. Midsummer is an odd time for an academic’s book to drop, since everyone is scattered, but I was able to bring a couple of hard copies to the ASLE conference in Portland.

In some ways the Introduction was a culmination of ideas I’ve been thinking about for the past 20-ish years, though in other ways writing a broad introduction, encompassing all seven seas and the full span of literary history, was a strange thing to write as someone trained in early modern English literary studies. I am sure many specialists, even those who enjoy the book, will twinge a bit when I cover such areas as modern Indian Ocean fiction or Indigenous Alaskan poetry. But I do know the Blue Humanities side of things pretty well, and I come to the other material in a spirit of watery community.

The only other book publication in ’23 was the translation into Italian of Oceano: Storie di marina, poesia, e globalizzazione, done by the good people at Wetlands Publishing in Venice from my 2020 Object Lessons book Ocean. I’m looking forward to visiting with them this coming February to do some slightly-late publicity.

In the articles and chapters category, I published “Surfing the Sublime: Tim Winton’s Breath and Eco-Heroism,” in SubStance (160: 52.1 (2023) 75-80), and “What Washes Up on the Beach: Shipwreck, Literary Culture, and Objects of Interpretation” in Sara Rich and Peter Campbell’s book, Contemporary Philosophy for Maritime Archeology: Flat Ontologies, Oceanic Thought, and the Anthropocene (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2023: 75-86).

I did a podcast with the New Books Network on An Introduction to the Blue Humanities, and a fun Zoom-conversation about the book with the Coastal Studies Reading Group. I also published a prose-poem looking back at my time in Bavaria last year, “Five Ways of Seeing the Steinsee” in the Rachel Carson Center’s online jounral Springs: The Rachel Carson Center Review 3 (2023).

Early ’24 will be busier, with Water and Cognition in Early Modern English Literature , a collection of essays co-edited with Nic Helms, coming out in March, and then Saliing without Ahab: Eco-Poetic Travels in April. More about them in the New Year!