I wanted to like Jorie Graham’s Sea Change more than I really like it.  I firmly believe in addressing our climate crisis with poetry as an important tool, and I also like the visual experiment of her two-pronged lines. The very long lines spilling on top of the very short lines — the left margin of the shorter lines begins in the middle of the page — creates a compelling asymmetry, a disorder or partial order that mimics the ecological processes she’s writing about. But the gaze remains too earth bound to really wow me.

I firmly believe in addressing our climate crisis with poetry as an important tool, and I also like the visual experiment of her two-pronged lines. The very long lines spilling on top of the very short lines — the left margin of the shorter lines begins in the middle of the page — creates a compelling asymmetry, a disorder or partial order that mimics the ecological processes she’s writing about. But the gaze remains too earth bound to really wow me.

She’s got some nice lines here, driven by careful focus and particularity of vision, as when she writes about the boundary between self and world through recognizing

how the world is our law, this indrifting of us

into us, a chorusing in us of elements, & how the

intermingling of us lacks in-

telligence…

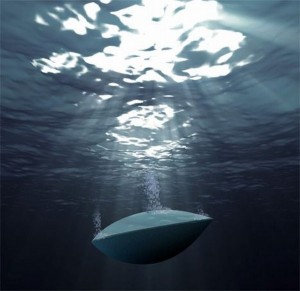

Perhaps it’s just that my blue water vision balks at too many leaves & branches, but the stronger poems here are really about midwestern winters and out of season blooms. She has one pretty good invocation of the deep blue in the poem “Full Fathom” —

…hiss of incomprehensible flat: distance: blue long-fingered ocean and its

nothing else: nothing in the above visible except

water

Of course I stumble over her “flat,” which is what the surface of the ocean never is, but she makes nice hash of Ariel’s anthem — “those were houses that were his eyes”; “there is a form of slavery in everything” — and struggles compellingly with the imposing meta narratives of climate change.

What I’m looking for is deeper and less familiar, I’m afraid.