Books piling up on my desk must be shelved now that spring break is over! Here are mini-reviews of three I especially liked —

A gorgeous multi-generational novel about the Danish island of Marstall from the mid-nineteenth century through the end of WWII, We the Drowned won the big Danish prizes before being translated into English in 2010 and appearing in the US last year. A big fat sea epic that’s worth its weight, this one comes with the usual allusions to Conrad and Melville, but unusually it’s not the big whale but Whitejacket that’s on the author’s mind. The men of Marstall are fishermen but also maritime warriors, and the progenitor of the novel, Laurids Madsen, seems to have sailed with Melville on board the Neversink.

A few quotations highlight the novel’s vast, powerful sweep —

The future that lay ahead of us consisted of more thrashings and death by drowning, and yet we longed for the sea. What did childhood mean to us? (90).

He learned a song that he sang to us for many years. He said it was the truest song every written about the sea:

Shave him and bash him,

Duck him and splash him,

Torture him and smash him,

And don’t let him go! (97; song also returns on 674)

Perhaps the most intriguing character is Klara Friis, a sea widow who inherits a shipbuilding business and then plans to save the population of the island by bankrupting its fleet. Writing to her son, who has (of course) run away to sea —

What does…a man do when he is held underwater? Does he fight to get up? No, his pride lies in his ability to hold his breath (609)

Great seafaring stuff. Worth teaching, perhaps, if it were not so long.

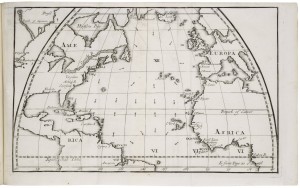

Next, Denis Cosgrove’s Apollo’s Eye, a wonderfully illustrated and brilliant survey of images of the globe from the classical period through today. Empire, he reminds us, is a “cartographic enterprise” (19). “To imagine the earth as a globe is essentially a visual act” (15). I’ll be dipping back into this one for years.

Third, and strangest, Elaine Morgan’s The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis, which argues that the particular evolutionary path taken by the first humans must have involved a prolonged period of semi-aquatic living, rather than only forest or savanna. She speculates that various features of modern humans, from a layer of fat under our skin to our relative hairlessness to bipedalism to our habit of breathing through our mouths as well as our noses, appear to connect humans to marine mammals as much as terrestrial primates. I don’t know how much credit she has in scientific circles — she writes like a semi-outlaw, without an academic byline — but it’s intriguing and almost persuasive.

Of course it’s not all that hard to convince me of a special connections between humans and seas.