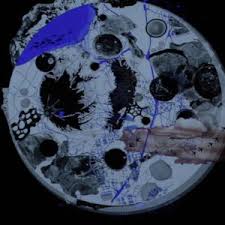

“Boring the Moon.” Photograph by Rosamund Purcell

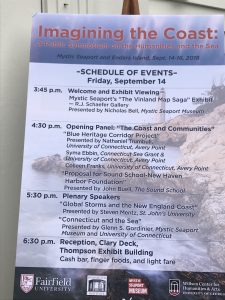

The full draft program for Creating Nature: Premodern Climate and the Environmental Humanities, is now online at Folgerpedia.

I’m excited to be co-organizing this event with Owen Williams of the Folger Institute. We’re asking how the premodern environmental humanities can speak to the eco-disorders of our past and present. The event will also work to expanding our cross-disciplinary capacities: the plenary will be co-delivered by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, a medieval literature scholar who’s recently crossed over to the Dean side, and Lindy Elkins-Tanton, the Principal Investigator for NASA’s planned mission to the asteroid Psyche. These two, who recently co-wrote the Object Lessons book Earth, will speak to a group that includes not only scholars working actively in early modern and medieval eco-studies but also practitioners of paleoclimatology, legal studies, philosophy, and anthropology.

Here’s the description of the event from the Folger site:

In the premodern past, weather was never just weather. Storms expressed the rage of gods, drought punished human sinfulness, and fires provided revelations straight from divine mouths. To suffer in hostile environments meant encountering more-than-human forces with merely human flesh. The inhuman power Shakespeare calls “great creating Nature” touches and sustains human bodies, but opaquely, and sometimes painfully. Nature is creator and created, force and object, destroyer and home.

This conference will bring together premodern environmental humanities scholars to explore the long and varied history of how humans have conceptualized their environment. Its invited speakers will explore historical and cultural forms in which humans have come to terms with their love for, dependence on, and need to manipulate the nonhuman world.

The distinguished speakers will cluster their conversations around four environmental keywords: “storms,” “sustenance,” “shelter,” and “spirits and science.” Together with the conference-goers welcomed into conversation, “Creating Nature” will provide insights into premodern ideas about human entanglement with the nature they knew themselves to be creating and the nature that created them.

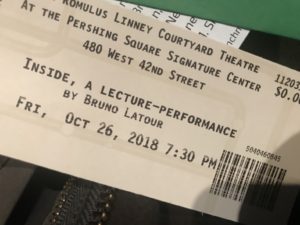

Over the six months remaining before we convene in Washington in May, I’ll intermittently blog about the conference. I’ll also link to related subjects, including the amazing eco-talk by Bruno Latour I saw in mid-town just before Halloween. Eventually I’ll gather the posts together on a Creating Nature webpage.

My opening post investigates the conference title.

It’s at the Folger and I’m co-organizing it, so it’ll surprise few people that the title comes from Shakespeare. But after however many years as card-carrying Shakespearean, I still find the phrase “great creating nature” hard to parse. I’ve been wrestling with the lines and the dynamic idea of Nature they imagine since grad-school in the ’90s. Back in 2015 I was fortunate to explore the exchange with the help of brilliant actors and directors at Loyola University of Chicago’s McElroy Shakespeare Celebration. After that talk-and-performance, I remember feeling “unsettled” about the “creating nature” exchange. I wanted to dig more into it — and I’m eager to do so with another amazing group of collaborators in DC this coming May.

In the sheep-sheering festival scene in The Winter’s Tale (4.4), King Polixenes debates Art and Nature with not-really-shepherdess Perdita. The King wonders why the foundling we know to be a princess refuses to plant streaked carnations, a popular hybrid species, in her garden. Perdita rejects them because

There is an art which in their piedness shares

With great creating Nature (4.4.87-88)

In an argument that has engaged and baffled literary critics for centuries, Polixenes counters Perdita’s anti-hybrid position with the claim that “the art itself is Nature” (4.4.97). Perdita’s desire to prohibit “Nature’s bastards” (4.4.83) from her garden seems an error of exclusion, and perhaps also an aesthetic narrowing. She craves simplicity while Polixenes champions complexity. Both believe they speak for natural truth, even though both arrive on the scene with their identities hidden. But neither regal authority nor youthful promise accurately maps the sinuous path creation takes in the redemptive second half of this play. At the heart of the exchange lies the unfathomable creative pressures of nonhuman Nature, the powers that make flowers and words, gardens and kingdoms. What happens when we can’t separate creators from created?

Our conference takes Shakespeare’s “creating nature” to limn the core paradox of environmentalism: that the ecosphere in which we live creates us while we re-create it. The shock of anthropogenic climate change in the present sometimes obscures the long cultural and physical histories in which humans have imagined, not always mistakenly, that climate responds to human actions, sinful or hubristic or fortunate. The ecological devastation of tropical island paradises from the Canaries to Easter Island provides a historical view onto today’s global environmental crisis. Weather emerges on the borders of understanding and experience. Systemic visions of climate from Aristotle to the Weather Channel posit structural forces that govern daily fluctuations. These changes carve themselves into human experience through the rawness of exposed skin in a storm, or the softness of a spring breeze.

We hope you’ll join us to explore how “Creating Nature” can help us understand the changes we are witnessing in our creating and created environments.

More soon!

When I left the theater around 10 pm, the rain fell heavy and thick, splashing hard onto my bald head. I darted beneath trees but was pretty wet by the time I got to my car. I missed my exit for the Whitestone Bridge and had to navigate a few treacherous puddles as I made a U-turn around the LaGuardia exits. Allegories abound in wet places: was I replaying the show, or extending it, or asking for a slight variation?

When I left the theater around 10 pm, the rain fell heavy and thick, splashing hard onto my bald head. I darted beneath trees but was pretty wet by the time I got to my car. I missed my exit for the Whitestone Bridge and had to navigate a few treacherous puddles as I made a U-turn around the LaGuardia exits. Allegories abound in wet places: was I replaying the show, or extending it, or asking for a slight variation?

In the final phrase of his dazzling “anti-TED talk” “

In the final phrase of his dazzling “anti-TED talk” “

Olivia and I decamped at the interval due to heat, impending murders, and in deference to her desire to see the big city after being cooped up in Stratford all week. So my thoughts of the Globe’s Othello end with 3.3, perhaps the most brutal and brilliant scene Shakespeare ever wrote, which takes the Moor from happy husband to sworn homicide. I would have liked to have seen the close, but I know how it ends!

Olivia and I decamped at the interval due to heat, impending murders, and in deference to her desire to see the big city after being cooped up in Stratford all week. So my thoughts of the Globe’s Othello end with 3.3, perhaps the most brutal and brilliant scene Shakespeare ever wrote, which takes the Moor from happy husband to sworn homicide. I would have liked to have seen the close, but I know how it ends!