In the final phrase of his dazzling “anti-TED talk” “Inside,” which I saw at the Linney Courtyard Theater on West 42nd St Friday night, Bruno Latour named his vision for the future as something that might “merit the term Renaissance.” I was surprised enough that I had to ask the person next to me, an eco-modernist from City College, if I’d heard the R-word correctly. Has the man who denied modernity gone over to the side of Rebirth?

In the final phrase of his dazzling “anti-TED talk” “Inside,” which I saw at the Linney Courtyard Theater on West 42nd St Friday night, Bruno Latour named his vision for the future as something that might “merit the term Renaissance.” I was surprised enough that I had to ask the person next to me, an eco-modernist from City College, if I’d heard the R-word correctly. Has the man who denied modernity gone over to the side of Rebirth?

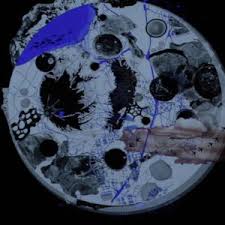

An image from Inside

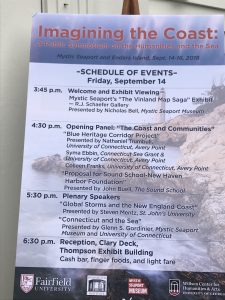

After joining everyone on my twitterfeed in reading an engaging profile of Latour in this week’s Times, I was excited for the “lecture-performance.” Latour’s part of the show was mostly lecture, but in front of him on the stage electronic images and graphics designed by Frédérique Ait-Touati superimposed themselves. The pictures started with a vision of the polar ice caps, which Latour said spoke to him on a flight from France to Calgary, and ended with a four-way image of the polarities of modern politics. One axis angled from the local to the global; its partner crossed between an empty circle that Latour associated with the current US President, matched against his hopes for what he calls “terrestrialism,” a way of living that engages with our shared planetary system in its era of stress. At its odd angle, terrestrialism represents Latour’s off-kilter optimism, his belief that ways of imagining our world — what he called “representations” throughout the lecture — can change political reality. Like his earlier notion of a “Parliament of Things,” his utopian future hinges on a radical expansion of representative democracy.

Much of “Inside” critiques traditional ways of thinking that Latour wants us to move beyond. Whatever his reservations about critique as a methodology, he ran through a litany of ideas he believes have distorted Western thinking. Here’s a partial list of Things Latour Doesn’t Like:

- Plato’s Cave, which insists that true reality lies Outside, rather than before our eyes on the surface of the planet where humans and “everything we have ever cared about” live.

- The desire to escape, which he suggests comes from, among other things, Plato’s cave. His hope throughout the lecture was to re-value being “inside,” rather than wanting to escape to an idealized or imaginary “outside.”

- The sublime as a way to relating to nonhuman nature, which he associates with imperialism and global conquest. He’s not wrong about intellectual history, but his comments on the sublime made me think that an important project for the environmental humanities might be to conceive a non-imperial, non-racist, non-sexist sublime. That project means recognizing and refusing the imperial dreams of mountain peaks and storms at sea, but maybe also salvaging something of the sublime’s open-ness to nonhuman experience. My money is on swimming, not rock climbing.

Stratigraphy

- The blue marble image of the planet seen from orbit, which Latour associates both with NASA’s drive to escape our terrestrial “inside” and with the global view, which he, in a moment of uncomfortable agreement with nefarious forces in our current politics, wishes to reject. He reads the globe the way Peter Sloterdijk does, as Western culture’s dominant image of totality, abstraction, and global conquest. He seeks a different model to understand our planetary home.

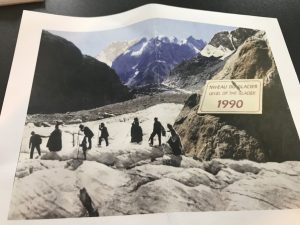

- Stratigraphy, which in a moment that surprised me he read as a problem, a lure into inhuman “deep time” which distracts and disorients human attention away from the terrestrial engagement at hand.

These elements all share a fundamental disorientation that historicist thinkers from Petrarch to Burckhardt to Foucault have associated with the sense of being “modern” that Latour has famously claimed we “have never been.” Disorientation, as I understood his lecture, emerges from the desire to escape from “inside” into a vastness and perspective from which we can see either the globe as a marble or human history as one more layer in the rock. He asked for a different response to disorientation, a burrowing into rather than escaping from the bounded experience of living on our planet. Trying out the thought experiment, I thought — as I often do — of a line from one of my favorite novels: “this is not a disentanglement from, but a progressive knotting into –”

A diagram of the local and the global

There are some things that can help. In its second half, “Inside” turned toward politics and also toward hope. Latour asked us to re-imagine being “inside” as a place of connection. The physical space he asked us to imagine was neither the globe as blue marble when viewed from orbit nor the deep layers of rock leading down toward the planetary core. Instead, he asked that we focus on what scientists call the “critical zone,” the narrow splash of “biofilm” that spreads across the earth’s surface and extends just “a few kilometers” above and below. Only on this thin, permeable layer, Latour reminded us, does life exist. It’s the space where living and nonliving things and systems interact. It’s where our bodies are, and where our attention should be.

He mentioned the word “Anthropocene” only one or two times in the lecture– he’s previously suggested that he doesn’t like the term — but when he talked about the Critical Zone I could not help thinking that he was asking Old Man Anthropos to look around his aging and broken body and remember that he’s only been in one place all this time. In a cave, on a thin membrane, inside the atmosphere, standing on rock, with wet toes on the edge of the sea — these are all the same place, from a certain point of view. Have we always and only been Inside?

By chance — we were two among 4+ million riders the subway last Friday — I bumped into my sister in the West 4th St station when I was moving between NYU and Latour’s lecture. She lives in Florida and I live in Connecticut. Coincidences happen!

I wondered if it matters, from the point of view of Inside-theory, that roughly 70% of the Critical Zone is covered by salt water.

I also wondered if Latour’s vision of science as a technique for re-enchantment, for revealing the nearly infinite richness of the limited and in a cosmic sense tiny world Inside, might prove useful in re-structuring an eco-sublime for our broken world. He spent some time, when talking about the science of measuring the Critical Zone, engaging with Thoreau’s Walden. (He also got some comedy out of pronouncing the American writer’s name in several different ways in his French accent.) I wondered not only about the canonical pond in Massachusetts, but also about Thoreau’s wilder and less settled spaces, from the shipwreck beaches of Cape Cod to his failed attempt to scale Mount Katahdin in Maine. The mountain that repulsed him generated some ecstatic language:

Man was not to be associated with it. It was Matter, vast, terrific…rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact!

The mountain-top sublime bears many too-familiar Romantic and imperialist flaws, including a worship of masculine power and solidity, a rejection of social and feminine spaces down below, and the belief in a super-reality — “Matter” — that exists only in solitary splendor at the uttermost edge of things. But I wonder, too, if the matter-of-fact-ness of Thoreau’s matter, its “rocks, trees, wind” and “solid earth,” might lend itself to reconceptualization via Latour’s networks and actants and desire to find all the imaginable riches Inside. Is there a salvageable sublime still to be found? Might that project be what Latour enigmatically called a “Renaissance”?

Bruno Latour

It was a stunning lecture, and a pleasure to attend with many of the amazing people from the French Natures “conference-festival” (shouldn’t all conferences also be festivals? an excellent idea!) that I caught a bit of at NYU earlier on Friday. Thanks to Phillip Usher, Frédérique Aït-Touati, and the other organizers, and also to Hannah Freed-Thali for a lively blue humanities-flavored talk about the modernist beach in French literary culture.

I’m looking forward to the English translation of Latour’s new book, Down to Earth, which should expand on many of these ideas!

Such a pleasure to spend three days in May eco-ing with such imaginative and generous colleagues!

Such a pleasure to spend three days in May eco-ing with such imaginative and generous colleagues!