[Guest Post by Nic Helms, Co-Neptune of the “Watery Thinking” Seminar]

It’s time for SAA 2020! It’s time for “Watery Thinking”!

At least, insofar as time still exists in the Time of COVID-19. It’s certainly more fluid, less about discrete chunks of time and more about flow. The Shakespeare Association of American 2020 conference has of course been canceled due to the ongoing pandemic. The work of SAA members continues, not in any normal way, but in fits and spurts, seeping through the cracks in between masked trips to the grocery store and far too many hours in Zoom meetings. Speaking as a current renewable-contract Instructor, for many of us that has always been where research happens: not in the Sea of Productivity, but in the underground streams, the culverts, the forgotten wells of stolen time.

Here’s our plan going forth. Months ago, we divided our seminar members up into the following groups:

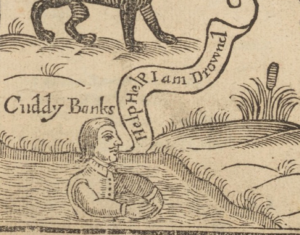

Drowning On Stage

- Lianne Habinek, “Ophelia with Spectator”

- Tony Perrello, “Monsters of the Deep”

- McKenna Rose “Muddy Waters”

- Myra Wright, “Sink or Swim”

Fluid Cognition

- Benjamin Bertram, “Richard’s Furnace-Burning Heart”

- Andrew S. Brown, “Sweet Waters”

- Douglas Clark, “Water is Best?: Cognitive Flux in Shakespeare”

Forms of Water

- Lowell Duckert, “Flake”

- Gwilym Jones, “As you to water would”

- Bill Kerwin, “River Memory”

- Rob Wakeman, “Biodiversity in the River Trent”

Submersive Tendencies

- Christopher Holmes, “Prospero’s B(ark)”

- Lyn Tribble, “An Alacrity in Sinking”

- Ben VanWagoner, “Capillary Imagination”

Our seminar members have shared their small group responses with the entire seminar as a way to get discussion flowing asynchronously on our Google Classroom page. In the next few days (and perhaps weeks, as time runs), we’ll hold much of our conversation online in that space. Due to the in-progress nature of much of our written work, this space will only be open to seminar members.

On Friday, April 17th, from 1:00 to 2:15 PM EDT, we’ll hold a synchronous Zoom session to approximate what would no doubt have been a lively conversation in Denver! This session will be open to auditors. Rather than post a public link, however, we’re asking that interested auditors RSVP by email to myself (nicholashelms@gmail.com) or Steve (mentzs@stjohns.edu). The first sixty minutes of the meeting time will be devoted to the seminar members and auditors will remain muted. The last fifteen minutes of our time will be open to auditor questions. We’ll use the “raise hand” feature of Zoom to organize the Q&A.

If you can scoop enough time into your cupped hands, join us to discuss wet environs and wetter minds!