The four talkers paced the backyard on a cold Wyoming night, seething.

Justin’s hand trembled as he prepared to disembowel a newly-shot deer. Teresa joyously proclaimed her readiness for the coming “war.” Emily ached with unlocated pain. Kevin gazed up at the stars and railed at his addition to the internet.

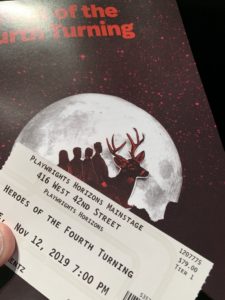

Will Arbery’s great new play, “Heroes of the Fourth Turning,” has under a week to go at the Playwright’s Horizon on Broadway’s edge. Many of the reviews that have made it one of the hot plays of the season have emphasized its ability to make urban liberals feel the feelings of rural Christians. But it’s better than that, and harder. The play, via the figure of Teresa, played with fire and charisma by Zoe Winters, scoffs at those of us who are “addicted to empathy.” That’s too simple an answer, too squishy and shareable. The truths this play’s after are less easy to assimilate.

Arbery comes by his knowledge of the play’s world biographically; his parents teach at Wyoming Catholic College and the character Gina, who arrives late to the party after having been named the new President of the College, appears to be based on his mother, Ginny. (The conservative author Rod Dreher, author of a brief for Christian separatism called The Benedict Option, which the play references, could not get to New York to see the production, but he’s written a compelling response to the screenplay based on his longtime relationship with the family.) Like many New Yorkers in the full house on Tuesday night, I was an outsider to the particulars of this world, but responded viscerally to the emotional force of the play. Theater is emotion concentrated, and that’s what we got last night on 42nd Street.

Teresa quote-evangelized paranoid theories of history – the “Fourth Turning” describes the coming generation of heroes, like the Civil War and World War II — she gleaned from Steve Bannon. Kevin vomited on stage, just a couple feet in front of my seat. Emily lovingly described her friend Olivia, who worked for Planned Parenthood. Justin quoted Latin poetry, Aristotle, and Plato.

Some of the chatter about the play has connected it to other “sympathy for Trump voters” efforts such as J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. But unlike Vance, whose memoir I found to be thin and self-serving, Arbery writes with an artist’s aggression and restlessness. We don’t need to like these characters. They aren’t charming. They’re feeling pain. They play asks us to take that pain seriously, whether we empathize or not.

Kevin declaimed Wordsworth’s “The world is too much with us, late and soon” in full. Emily got embarrassed when her mom showed up drunk to the party. Justin carried Emily since it was too painful for her to walk. Teresa developed a cocaine habit while living in Brooklyn.

The notion that the cultural war might devolve into real combat shadows the evening’s conversation, from Teresa’s ecstatic and Bannon-sourced prediction that “war is coming” to the pistol Justin carried in his back pocket to the recurrent references to electoral politics. All four of the talkers distrust Trump but voted for him. All four resist and resent mainstream American culture. All share a sense of solidarity through cultural resistance, of being a select but imperiled group. “There’s more of them than us,” Justin says mournfully, deliberately overlooking the current levers of power owned by the American right.

Emily howled forth the pain of a desperate and angry Chicago woman she counseled at a pro-life center. Justin played guitar and sang about the comforts of “nothing.” Teresa asked her former professor to blurb her forthcoming book of Breitbart-esque vitriol. Kevin craved a “big conversation.” Also a girlfriend.

In several moments, the play interrogated but also simply presented Catholic orthodoxy to view. John Zdrojeski’s manic Kevin gushed a graphic, description of the Eucharist. Along with Jeb Kraeger’s powerful Justin, he and Tesera voiced a collective rosary. July McDermott’s Emily appealed to the person I imagine to be Arbery’s ideal writer, “Flannery O.” These materials together assumed a powerful strangeness in performance. I’m a standard-issue academic lefty and seldom a churchgoer, though working for more than a dozen years at a Catholic University has given me a window onto the richness of Catholic social thought, its uncompromising resistance to certain aspects of modernity — Justin, who often serves as a moral compass in the play, rejects LBGTQ people unambiguously — and its deep attachment to classical and Biblical texts. The dissonance of “Heroes” felt a little familiar to me.

A painful screech scoured the stage several times during the performance. Justin said it was a malfunctioning generator, but then later admitted he had been lying about that. The struggle of a soul in agony? It never quite became clear.

Gina — Emily’s mother, former professor of Teresa, Justin, and Kevin, and newly elected President of Transfiguration College — arrived late to the party. She denounced Teresa, suggested she may hire Kevin as a new Director of Admissions, rejected Justin’s idea to add marksmanship to the College curriculum, and — heartbreakingly — appeared not quite to believe in her daughter Emily’s pain. Pain functioned as the basic currency of this world, and Gina’s inability to see her daughter felt to me unforgivable.

Motherhood, symbolic and literal, occupies at the play’s red-hot core. Gina’s triumphant claim to Christian sacrifice, which she pounded into Teresa during an argumentative climax, built itself atop the physical risk and suffering of eight C-sections and eight babies. Kevin opened his “big conversation” with Teresa wondering why he had to venerate the Virgin Mary. Emily did tell Justin at one point that she thinks he’d make a great Dad, but fatherhood stayed off stage. Mothers are the mystery, the flesh, the suffering. Gina genuflected to her academic husband’s “brilliance,” but admitted that she was glad that she was the one chosen to be the next College President. Abortion politics, raw and uncompromisable, shadowed everything. (By coincidence, I came across my one-time colleague Caitlin Flanagan’s visceral entry into the abortion debate just a half-hour before the show, which seemed appropriate. Flanagan ends up seeing the debate as unsolvable. I wonder what she’d make of this play?)

Not much time left, but if you can, get to West 42nd St to see one of the last shows! And put Will Arbery on the list of names to watch.