I walked into the empty room just before the apocalypse.

I’ve never fully shaken the foreboding time-feeling of MLA, an anticipatory anxiety that lingers from my can-I-stay-in-this-profession early years in the ’90s (when, I know, things were much less dire for me than they are now for the current academic generation). The feeling of disaster about to burst also echoes today’s environmental bubbling-over, as bushfires and floods light up our screens large and small, even if we are lucky enough to be far from these catastrophes at least some of the time. I got to room 604 of the Washington State Convention Center early Sunday morning, wanting to set the scene for the beastly glories of session #666, lurking in the hangover slot to close out my MLA. The room was empty. I moved some chairs and appropriated a red “1 Minute” sign that, as it turned out, I would not need. The half-dozen demon-sharp speakers who would comprise the “Spenser, Ecology, and the Dream of a Legible Environment” panel filed in on time, with their brilliant talks that would take us from bleeding forests and courtrooms all the way to New Jerusalems and Silicon Valley’s posthuman paradises. Our session was marked by the beast’s number and haunted by visions of exhausted and “uninhabitable” earths. The panel didn’t proffer facile optimism but did show us ways, to adapt Alex McAdams’s great eco-analysis of the Legend of Temperance, to walk out “while weather serves, and wind” (Faerie Queene 2.12.88.9).

The panel’s pattern of looming catastrophe confronted if perhaps not averted parallels my sense of this year’s deeply engaging and mostly heartening MLA. The big conference provides snapshots of the states of our fields and subfields. There was much excellence on display. More than any MLA I’ve ever attended, the conversations I followed this year seemed driven by access and in particular a focus on new voices and methodologies. The continuing tide of eco-humanities was strongly present, and eco-trends have begun productively to engage with Critical Race Theory, feminism, globalization studies, and, to an extent that I hope will increase in time, Indigenous Studies. (I note also that this was the first MLA at which I heard, and delivered, land acknowledgments to the indigenous peoples of Coast Salish– though not at every session.)

As an early modernist, I felt some of most influential voices at #mla2020 were a pair of women who were not there, Kim Hall and Ayanna Thompson, whose years of work, insight, and field-shaping advocacy shaped not only the three connected #racebeforerace panels sponsored by the 17c English forum but also many other panels and presentations, including a collaborative panel organized jointly by 16c English and the Global Arab and Arab-American forums, and Dyani Johns Taff’s great talk on my own Eco-Spenser panel about the raced and sexed nonhuman bodies of Scylla and Charybdis. It was great to witness the groundswell of CRT-inflected early modern material being presented, driven and connected by the #racebeforerace and #Shakerace hashtags.

Thinking about the many panels I heard at the conference, the brilliance of early-career scholars and graduate students stands out. At this point, I can’t claim to be surprised to hear incisive and tightly-crafted analyses by Ambereen Dadabhoy, but I feel fortunate to have listened to her speak twice in two days. Insightful thinking from Will Rhodes on Spenser’s colonial ecologies, Connie Scozzaro on love drugs in Midsummer Night’s Dream, Alex McAdams on time and ecology in Spenser, Katherine Cox on climate change in Paradise Lost, and Mira Kafantaris on the racial symbology of Spenser’s Duessa confirms that we’re in the middle of a surge of great new scholarship in early modern literary culture.

The old shadow-MLA of hotel room interviews wasn’t as much in evidence this year, at least not for an old guy like me, but I can’t help thinking there was a different ghost conference in Seattle this year. Sessions that addressed the state and emerging futures of the profession – the form of our scholarly lives, rather than the content of our analyses – were markedly less sanguine than those that dove into new analyses of literary texts. I believe deeply in the work we are doing collectively, in the values of words and stories to counter climate apocalypse and resurgent racism and misogyny – but it’s hard to feel optimistic on the professional front. It’s hard to be optimistic on many fronts, actually, though I also think one of the lessons of ecocriticism in the face of increasingly dire climate news is that too-simple optimism, visions of transformation or “discovery,” tend to conceal violence and dispossession. We need to learn to live and work toward justice inside climate dynamism, not ascend to a catastrophe-free and morally purified future.

A notable session organized by Drew Daniel on “No Fear Shakespeare” represented a telling mixture of stirring content and dispiriting awareness of the cultural challenges alongside which we profess our profession. The pivot paper by Stephen Guy-Bray on what the No Fear paraphrases of the sonnets exclude was delicious and dazzling, a testament to Stephen’s wit, insight, and abiding commitment to poetic beauty. Great as the talk was, however, I left wondering if he’d followed the easier path. The opening and closing papers by Ann Christensen and Christine Hoffmann turned from texts to classrooms and into the wilds of web culture to propose strategies for pre-emptive annotation (Christensen) or for sympathetic engagement with making Shakespeare less frightening in our interwebbed world (Hoffmann). Their presentations addressed, with difficulty and sometimes a sense of not being able to clarify or salvage everything, the mixed and messy cultural experiences that spill into our classrooms, not to mention our lives. I love the intricacy of poetic gems as much as Stephen does – or almost as much, maybe – but I also valued the effort in this panel to marry pedagogy, formal analysis, and web-inflected cultural breadth of vision. Can we do all these things at once? Let’s hope so! But I think we can also expect not always to get everything right all the time.

MLA 2020 marks the end of my five-year run on the 16c English Forum board, which means I’ll shift to a not-every-year MLA schedule and won’t be conspiring on a pair of guaranteed sessions after next year. It’ll be nice to be released from mandatory attendance, but I’m proud of the work the 16c English Forum has done over the years, bringing new people into presentations and board membership and sponsoring lively discussions on such always-fascinating topics as Tyranny, Flattery, and Radical Hope. (Not every one of these panels doubled as a how-to class, I’m happy to say.)

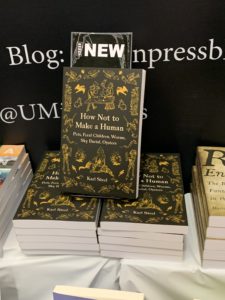

Chairing my final session for the 16c English forum about Spenser makes me want to find a suitable allegorical moment to enclose in transparent glass. What was the crystalline heart of #mla2020? I’m tempted to nominate the welcome choice of Jonathan Eburne’s Outsider Theory as the James Russell Lowell prize-winning book. This book’s focus on the strange and its possibilities shines light on the work of the University of Minnesota Press in supporting experimental, speculative, and inspiring scholarship, through the editorial leadership of Doug Armato and many other excellent people, past and present, at the Press. (Full disclosure: UMP published Shipwreck Modernity and most recently Break Up the Anthropocene, and I love working with them.)

But I can’t helping thinking about a more enigmatic, and, alas, somewhat less hopeful, scene. Guided by Seattle native Lowell Duckert, a group of us found our way through rain and steep sidewalks into the enticing open glen of a local brewery the name of which is now lost to time. Surrounded by gleaming vats and hand-written signs on the wall. we sought to decipher the many IPAs on the chalkboard. Too soon, we realized that our cross-town dinner reservation was a full fifteen minutes away. Sadly beerless, we piled into cars & arrived just in time for a tasty and festive meal, though, more’s the pity, at a spot that served cider instead of beer.

The moment in that allegorical cave when I lost my taste of Seattle’s local brews to time accents the way that MLA always feels like a battle against temporal limits. There’s just not enough time! As ecocritic Tobias Menely emphasized in his wide-ranging analysis of Paradise Lost and climate change, time remains our hardest and most urgent challenge in thinking ecologically, as well as in thinking about literary culture and perhaps also about the trials of the 21c professoriate. Shakespeare’s sonnets, like ecological analysis, engage the paradoxes of multiple overlapping time spans, including the lives of poet, poem, beloved, and our ruined and ruinous earth. What do the riches of the beer unpoured promise, even as the door closes (forever?) on that secret taproom?

I know what I want from MLA and the future of our profession. I saw it in the work and imagination of so many colleagues, including the six demonic Spenser-lovers who found in the “dream of a legible environment” visions of possibility amid destructive change. I saw things to admire in the work of the brilliant alums of the new PhD program in English I have helped shepherd into being over the past decade at my home university of St. John’s, including Dan Dissinger’s expansive sense of writing studies, John Misak’s gamified Hamlet, and Laura Lisabeth’s ethical commitments to pedagogy and writing studies. I’ll also shout out one more not-yet-graduate of SJU who I spotted amid the MLA press, Tina Iemma, for her #bigger6 work within and beyond Romanticism.

I’d like a profession welcoming enough to welcome them, and the other brilliant voices whose work I heard and learned from in Seattle this weekend, and over the past many years of MLA.

That’s not too much to ask, is it?