I slurped this one down in one go last night, sneaking in a personal treat at the start of winter break. Peter Coviello’s Vineland Reread, his entry in Columbia UP’s Rereadings series, ranges across a series of encounters with Pynchon’s relatively unloved “middle” novel, which Coviello contextualizes as occupying a near mid-point in the writer’s career, having appeared in 1990 after the long hiatus post-Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and before the more consistent run of subsequent novels, Mason & Dixon (1997), Against the Day (2006), Inherent Vice (2009), and Bleeding Edge (2013). Like me, Coviello hopes that the now 82-year-old Pynchon might still have a novel or three still up his sleeve; like me, he also suspects that the epics GR and M&D will punctuate the career. But if Vineland sometimes gets judged as middle in quality as well as chronology, Coviello makes a convincing case for the novel’s prescience, its subtlety, its loss-haunted history of America, and — above all, and most powerfully in this smart, funny, inventive passionate book — its syntactic joys. It’s hinge-Pynchon, connecting the tragic early brilliance to the ramshackle later works. It’s also just plain brilliant. Maybe the non-epic novels give an even clearer view of the distinctive flavors and energies of Pynchon?

There’s nothing quite like the swoops and dives, elaborate curls and dead-ends, the ambition and profligacy of the Pynchon sentence. Like many Pynchon-stans, my baseline response to my favorite sentences is how’d-he-do-that wonder, even if, as is often the case, the dog being chased through many clauses and elaborations turns out very much of the shaggy variety. Coviello strikes a finely calibrated balance between explaining the complexities of Pynchon’s style and also wallowing in its abundance, goofiness, and high-wire-act displays. I read a lot of academic prose, and it’s always a temptation to skip block quotations, especially since the quoted texts are often things I’ve read before — but part of the joy of this book for a confirmed Pynchonophile is anticipating where Coviello will lard in the juiciest bits. I guessed that he’d last-word his book with the rousing Emersonianism of the Becker-Traverse family reunion — “It is impossible to tilt the beam” &c (122) — but he snuck in early the Star Wars-inflected confrontation between Prairie and her dark father nemesis (46-47). Like Coviello, I am “a child of the seventies and eighties” (47), so I was already there for Brock Vond as Darth Vader. But since I’m mostly a Shakespearean and only read Pynchon criticism in a recreational capacity, I’d not previously worked out how thoroughly this sort of intertext works. For my teaching, next time, if/when I reanimate the Pynchon’s California course! (I have been thinking about Pynchon’s New York, but I’d have to figure out how to teach V.…)

The lasting feeling I take from my chug-a-lug of this delicious little book is its hymns to readerly joy, the riotous pleasures of these sentences and novels. Coviello knows he can’t really capture all of that lightning-in-a-bottle sensation, but he also captures it pretty well. Reading Pynchon is “filled with an anarchic sense of possibility expanding in dizzying breadth from the page” (5). Talking with fellow obsessive readers forms private utopias that “out of the sheer abundance of their enthusiasm find themselves fabulating these semiprivate codes and idiolects” (27). Sharing this writer produces not the self-shattering of jouissance but “a momentary inflooding sense of abundance, a richness of pleasure that amplifies itself in its sharing” (35). Yep, that’s it.

Darkness and history loom and shadow, and Coviello unpacks in Vineland‘s Reagan-centric vision unsettling anticipations of the twenty-first century systems unsatisfactorily collected under the term “neoliberalism.” But if “every We-system is also a They-system,” as the paranoid genius of Gravity’s Rainbow proclaimed, the more empathetic spark of Pynchon’s post-1990s vision recognizes liberal complicity — arch-villain Brock Vond’s “genius was to have seen in the sixties left not threats to order but unacknowledged desires for it” (Vineland 269) — with which the less-trusting-than-thou novelist participates with varying levels of reluctance and eagerness.

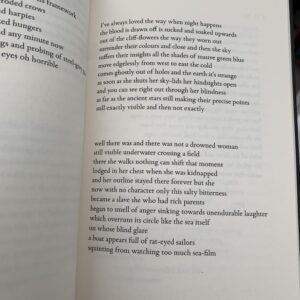

It’s a backward-nesting faux-irony, a kind of humanized empathetic counter-challenge against and complicity with the rage and fire of the Rocket-world, that I most love about post-90s Pynchon. Since like Coviello I can’t really resist, I’ll close with two favs. First, from Mason & Dixon, which like Coviello I read as the masterpiece toward which Vineland lays the path. This passage describes carving the Line through America, and also reading-as-life-practice:

Newcomers to the Ley-born Life are advis’d not to look up, lest, seiz’d by its proper Vertigo, they fall into the Sky.–For ‘t has happen’d more than once,– drovers and Army officers swear to it,– as if Gravity along the Visto, is become locally less important than Rapture.

Mason & Dixon (651)

In its side-eye glance at the V-2’s destructive descent in Gravity’s Rainbow, its anxiety about its own fall, or should we (always) say Fall in its Miltonic sense, its pastiche of eighteenth-century punctuation, and its allegorization of interpretive practices from the surveyors to the drovers to we readers, I take immoderate joy in this sentence.

But right now through Coviello I’m rethinking Vineland, which isn’t just a warm-up to M&D. My closer quote comes courtesy of one of Pynchon’s nonhuman characters, following one of a few threads Vineland Reread mostly doesn’t pull but which might gesture toward some partial freedom from human self-delusions, the last-page return of Desmond the dog, licking Prairie’s face and providing the first clearly, overtly, even excessively optimistic ending in Pynchon’s career:

It was Desmond, none other…roughened by the miles, face full of blue-jay feathers, smiling out of his eyes, wagging his tail, thinking he must be home.

Vineland 385

Home as dog-imagined maybe gives us enough wiggle to import some human(e) skepticism also, and the munched blue jays reprise and revenge the birds who woke Zoyd up on the first page of the novel, as well as gesturing to the “boys in blue” who raid NoCal utopias and the oft-mentioned blue eyes of both Prairie and her mother Frenesi. Does this blue-cycle connect to my own blue water obsessions? I’ve toyed with a reading of surfer allegory in an essay on Inherent Vice in tandem with Spenser’s Faerie Queene (in the 2017 collection Veer Ecology), and more might be said about Pynchon’s oceanic moods. But that’s for another, or never, time.

Thanks for this book, Peter Coviello! Any chance you’ve got a sequel in the works about Inherent Vice?