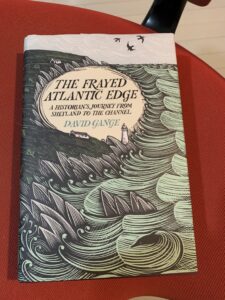

The final paragraphs of David Gange’s glorious historian’s adventure, The Frayed Atlantic Edge, arrive with startling clarity. We must change the way we think about nature, the sea, and “Romanticism.” Gange distinguishes his immersive practice from naive or sentimental forms of Romanticist thinking:

It isn’t romanticism that needs to be cleared from perspectives on these places, but the assumption that these communities somehow belong to the past, not the future, and are merely hazy places to escape to.

In rejecting Romanticist nostalgia, Gange asks instead for a future-oriented engagement with oceanic edges and humans that make their lives across watery borders:

…the journey had shown me that a romanticism which delves into the natures of humans and their fellow species, finding wonder while rooted in the real, might not be so naive after all.

That’s right, I thought to myself as I closed the book last night. That’s exactly right. The practice of immersive contact with humans and nonhumans, watery and windy spaces, generates in this book what we might call a material romanticism that connects the “wonder” with the “real.”

Thinking about that insight this morning has me recalling the risks and hazards of immersion, from physical danger to sentimental stories. Gange’s journey by kayak along the Atlantic coasts of Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall ended with him fleeing the tourist mecca of St. Ives to spend a landless night keeping his kayak afloat at the Seven Stones, which appeared to his waterbound perspective as “less like a wall in front of waves and more like a knife blade thrust into ocean.” This starkly Romantic moment, in which the solitary boatsman holds himself upright all night through the painful exertions of tired arms, anticipates the book’s final turn toward a new romanticism of material connections and future orientations in the final pages.

Bruno Latour wrote several years ago that the “successor to the sublime is under construction” during our Anthropocene era. That project of assemblage or re-making seems to me the urgent task of our day. To replace the ego-dwarfing separations of Wordsworth and Shelley with something smaller, harder, more abrasive, directly material, and more obliquely emotional may enable a new poetics of the encounter for Anthropocene days.

[Note to self: extended quarantine might be a good time to sketch that long-deferred history of the literary sublime, from Longinus to Shakespeare & Milton, Melville & Dickinson, Thomas Pynchon & Toni Morrison… Sounds a bit like boring lit crit, as I churn out the list, but maybe…]

But now, before the Zooms of the day, a few thoughts on The Frayed Atlantic Edge, its insights and its joys.

Structure seems so essential: Gange’s book constructs itself through eleven mostly-solo journeys by kayak along the Atlantic shoreline from Shetland (July) to Cornwall (the following July). Each adventure combines paddling with reading, plus inspiring descriptions of local poets and communities. A few touchstones emerge along the rocky shorelines.

“If timelessness exists anywhere on earth, it is not in sight of the sea,” Gange writes while off the Orkney coast. Dynamism and physical experiences of change typify these violent spaces.

Another important argument asks us to re-orient the history of the British Isles away from inland cities and toward ocean-facing coasts. Drawing on the inspirational work of Barry Cunliffe, Gange emphasizes the ancient patterns of exchange that have dominated seaboard life since the Mesolithic period. He speculates that the dominance of collective agriculture and urban population centers have produced a series of myths through which “‘we Mesopotamians’ have constructed the separation of people and nature.” Against that fundamental agricultural split — on which point see also Tim Morton’s eco-theory and James Scott’s pre-history — Gange hazards that “Mesolithic seafarers … [may be] the only humans in the whole of time and space who are not the ‘anthro’ in Anthropocene.”

At the core of this book’s coast-centric vision is a rejection of what Gange calls the “thalassophobia” of modernity, especially urban modernity. The villain in Gange’s history is clearly the railroad, which re-orients local travel and commerce inland rather than along the crooked and inviting shoreline. To write ocean history, he suggests, is to write against grand narratives of conquering nature and toward what Rachel Carson calls a “sea ethic.”

I’ve been reading this book during prolonged swim-less quarantine. The local pools are all closed, and an especially chilly April and early May has kept me out of Long Island Sound’s gray-green embrace. Soon — maybe this weekend? — I’ll start back in with my daily high tide swims. Immersion will help me organize my summer, which was supposed to include swim trips to the Irish Sea among other places, into a more local swim-write-sleep-repeat pattern. I think a lot about the offshore perspective afforded by the blue humanities and its dream of immersion. Reading The Frayed Atlantic Edge during these dry quarantine weeks recalls the edge-feelings that writing at its best can pry out from subconscious and submarine depths, and the fraying pressure of material experience. Gange’s willingness to embody his academic practice, and also his precise, wistful, evocative prose provides a thrillingly immersive model in the wake of which many of us are likely to be paddling more a long time.