Some time during pandemic winter, it’s hard to remember exactly when, I was on Zoom listening to some St. John’s students reading their original poetry. One student, whose name I didn’t recognize because he started the PhD program during the year of social distancing & hadn’t taken a class with me yet, said that he had a book of poems coming out in 2021, and that he normally writes about the ocean, fatherhood, and ideas of orientation in a maritime context.

I thought for a minute he was introducing me. I don’t have a book of poems coming out, but — oceans, fatherhood, orientation? Really? I mean, I’ve heard of people who are interested in such things. I see their faces every morning in the bathroom mirror.

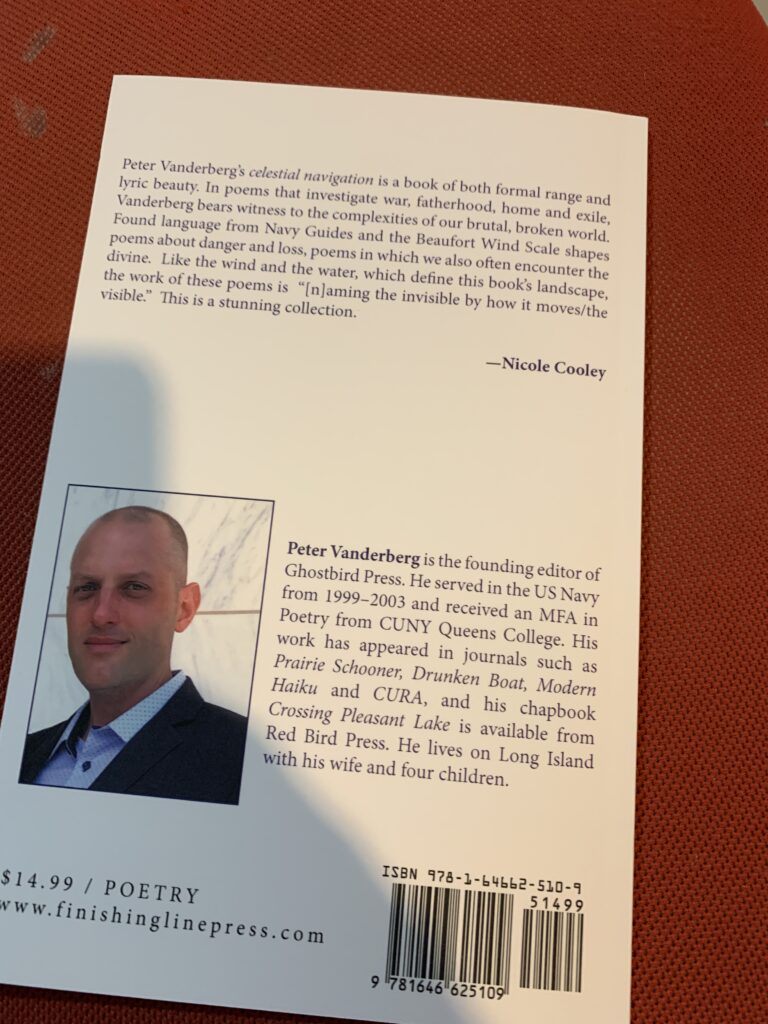

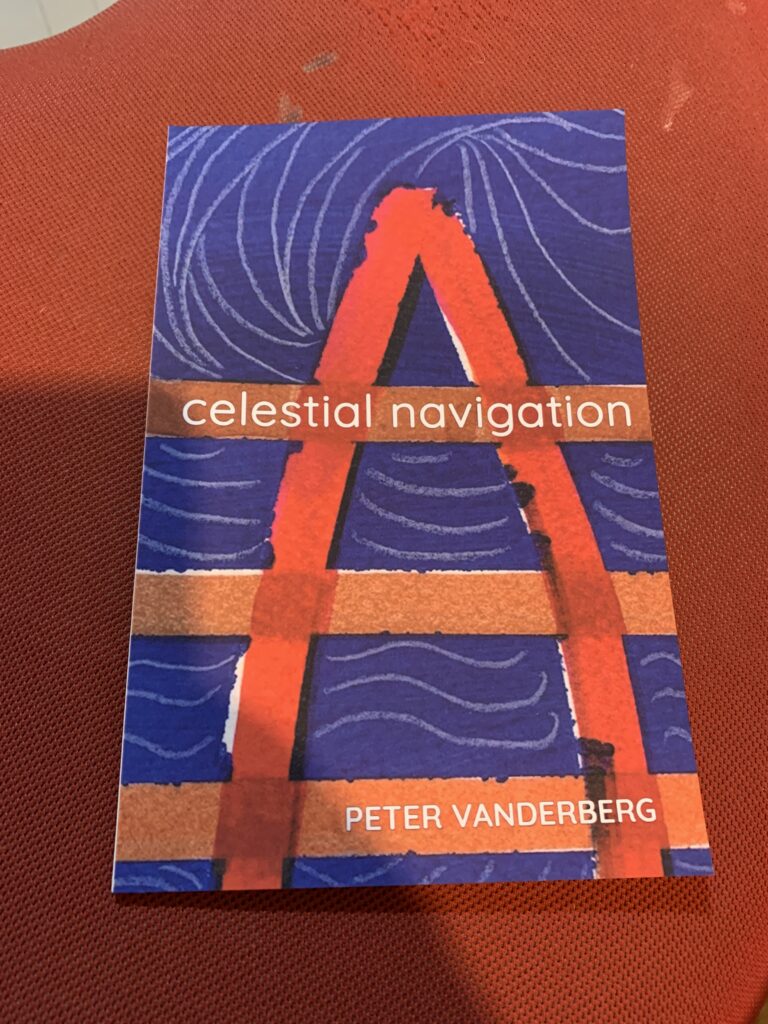

Earlier this week I received a copy of Celestial Navigation, Peter’s new book from Finishing Line Press. A few differences helped clarify the question of identity — he has four kids while I only have two, he served in the US Navy from 1999-2003 when I was finishing grad school, he lives on the southern side of Long Island Sound while I live on the north. He has an MFA; I have an MA and a PhD. He’s a bit free-er than I am with line length and positioning, but that may also be that I’ve been writing dozens upon dozens of pretty regular sonnets during these pandemic months. Blessed rage for order, as somebody says.

My favorite poem in this lovely little book is “Scattered White Horses,” a sixteen-line mini-epic about fathers and sons and the sea and a “proof of mythology” that gets passed down, or maybe doesn’t, or doesn’t need to be, because the objects that assume meanings cohere by themselves —

The strange thing is that mythology requires such few proofs

seagulls crying over my father’s house

my grandfather’s bent finger, a knife in my pocket —

& that these made the other side of the world less strange to me

There are gorgeous partly-found poems built out of Navy documents and manuals, moving poems about families and distance, poems about sea storms and breezes — the “scattered white horses” show up in another poem as whitecaps on the water — and on war and the Beaufort Wind Scale.

A lovely and moving book of poems that everyone should read!