Last Saturday night in Manhattan I saw two icons of beauty: a young girl with (to quote Jane Austen) “fine eyes,” and an actor in drag. Not sure which was more bewitching.

Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring is visiting NYC while her home in the Maruitshuis is undergoing renovations. She’s been at the Frick since October, packing in the crowds. The line outside the museum on Sat afternoon snaked around 70th street and halfway up the next block of 5th Ave, filled with dueling umbrellas and fractious children.

It’s an odd thing to stare intently at a small canvas in a crowded room, seeing for the first time the original of such a familiar image. What do we see, or seek, in those luminous eyes, reflecting the light of the over-sized pearl hanging from her left ear? Stillness after motion, as she turns ambivalently to look at us. To sit for a portrait is to release your face into History. With getting too Tracy Chevalier, Vermeer’s Girl looks as if she’s hiding something.

I was struck by the oddly dynamic shape of the eyes-pearl triangle, three moons pulling my gaze across and downward to the right, away from her expressive face. The gallery notes emphasize that no pearl of that size has been discovered in Vermeer’s inventory, so presumably it’s a symbol. The soul of great price or South Sea pearl divers? Must be both, always.

Knowing what to do, we left in time to grab dinner in mid-town and arrive early at the Bellasco Theater, where we watched the actors get into costume. The costumes were made mostly with period technologies, and the female outfits were especially elaborate, long dark gowns and high ruffs, powerful armor against the world as the household retreated in mourning for a lost brother. Mark Rylance’s Olivia stood perfectly still and straight when being dressing, luxuriating in the power and stillness of her stiff black dress.

I was expecting a lot from Rylance, in a role that so many critics have celebrated. I wasn’t disappointed. I wanted to try to figure out how he does it. Protected by costume, make-up, and crown, his performance hid from us at the start. Playing Olivia’s intense desire to retreat from the world, and the sudden upending of that desire when “Cesario” speaks to her, Rylance focused our attention on tiny, revealing movements: her gliding feet invisible under the dress, the halt in her voice when she desires Cesario to come again even though his errand for the Duke is hopeless, the show-stopper later in the action when she swings a 10-foot halberd to discourage Sir Andrew from fighting her page-boy love. My favorite moment was her little two-footed hop when, near the end, she sees both twins, Sebastian who she’s secretly married and Cesario who she’s been wooing for much of the play, on stage together: “Most wonderful!” (5.1.225). Give me excess of it!

It makes me think that powerful acting isn’t only about communication or making emotions accessible — I think by contrast of Derek Jacobi’s needy, petulant, child-like Lear — but about the struggle of human character to reveal itself. Much of what we see and react to is concealed emotion, the just-legible bits leaking out around the edges. We feel it most when we barely see it. Audiences are like Malvolio: pleased to discover things that have been invented for us.

The overall production, which traveled to Broadway from the Globe in London, was excellent in a down-the-middle modern Globe way that didn’t challenge my notions of the play: a fine, tall, goofy Andrew Aguecheck by Angus Wright, whipsmart Maria by Paul Chahidi, as engaging a singing voice by Peter Hamilton Dyer as Feste as I’ve ever heard in the role, Stephen Fry’s Malvolio made livelier by his recent turn as the Master of Laketown in Hobbit 2: The Interminalness of Smaug. But Rylance’s performance, especially its controlled moments early in the play, when his Olivia still wished to mourn alone, and then the precise, just-visible cracks that came with the impress of love from Cesario’s face and voice, produces a (non-directorial?) interpretation: Twelfth Night‘s about how mourning ends. Neither black gowns nor desperate grief can smother life. That spark is what we like to watch.

Sir Toby has it right: “I am sure care’s an enemy to life” (1.3).

Sir Toby has it right: “I am sure care’s an enemy to life” (1.3).

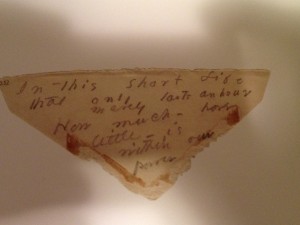

Which brings me back to Vermeer’s Girl. When working on a New Year’s purge of files from my overflowing home office a few weeks back, I found the paper I wrote for Baroque Art, with Professor John Martin, back in 1988 (or so), about Vermeer. Not the Girl with a Pearl Earring, which I’d never seen before last week, but her companion a few blocks uptown, Young Woman with a Water Jug. My essay, typo-saturated I’m sorry to say, explored “allegory as technique,” by which phrase I was trying to get at the overlap between the painter’s intense realism and the painting’s equally potent symbolic charge. The pearl that is is both soul and eyes, the girl’s eyes that are both pearls and unique signifiers of a particular self, the water jug and map and shimmering light that are both real things and inescapably metaphoric. I’m after the same things a quarter-century later.

The liveliest thing about art, from iconic paintings to vanishing performances, is the pressure it can put on places and objects and bodies, the way it insists on the dual force and fundamental unity of material and metaphor.

The liveliest thing about art, from iconic paintings to vanishing performances, is the pressure it can put on places and objects and bodies, the way it insists on the dual force and fundamental unity of material and metaphor.