Without doubt, it was the wettest shipwreck scene I’ve ever seen, in my many years of seeing productions of The Tempest. Probably the best, too.

Synetic Theater’s game is Silent Shakespeare, no words spoken at all, though Stephano did hum a sea chanty at one point. I’ve heard about this company for a long time, and almost got tickets to a staging of Don Quixote a year or two ago — but I must admit it was the flooded stage that drew me down to DC. It’s been a great short trip, with a couple of half-days in the Folger reading piscatorial verse, and a happily-timed jaunt over to Foggy Bottom to listen to Will Stockton say brilliant things about Romeo and Juliet. But let’s not kid ourselves: it was the water, 4″ of it all over the stage, that punched my ticket.

Synetic Theater’s game is Silent Shakespeare, no words spoken at all, though Stephano did hum a sea chanty at one point. I’ve heard about this company for a long time, and almost got tickets to a staging of Don Quixote a year or two ago — but I must admit it was the flooded stage that drew me down to DC. It’s been a great short trip, with a couple of half-days in the Folger reading piscatorial verse, and a happily-timed jaunt over to Foggy Bottom to listen to Will Stockton say brilliant things about Romeo and Juliet. But let’s not kid ourselves: it was the water, 4″ of it all over the stage, that punched my ticket.

When I got to the theater in the basement of an office building in Crystal City, they handed me a poncho to take to my seat. I’m glad I put it on, though it didn’t really keep me dry.

Liberated from the text, the Synetic production made some interesting decisions about narrative arc. They opened with the arrival of young Prospero and a swaddled infant Miranda on the isle, guided by spirits and music from a piano that spouted an arching waterfall from beneath its waterlogged keys. The piano, perhaps the source of Ariel’s power, was the only prop on stage beyond the water itself. Ariel played it, Ferdinand scrubbed it, Caliban jumped on top of it, and the young lovers first glimpsed each other through the waterfall beneath which Miranda was hiding. Music and water together.

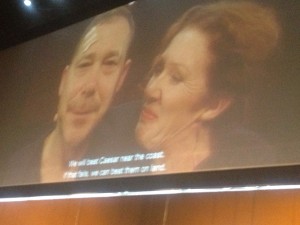

The splashing started with a Gandalf-v-Saruman style fight scene between Prospero and Sycorax, in the course of which he wrested a staff from her and stubbled her with it while I and the other Splash Zoners got our first taste of the water. Sycorax and her son dressed in red body suits, Caliban’s sporting horns, but when he prodded his mother’s still form after she’d been laid low by our hero, the feel of his character — here and elsewhere — was more puppy than devil. As Prospero learned his way around the island, freeing Ariel from imprisonment and looking after soon-teenage Miranda, Caliban, having no choice, slowly warmed to his mother’s killer. Before the Italian ship arrived they were a happy-ish quartet, with girlish Miranda leaping around the watery stage with Caliban.

The play told its story through broad, playful physical movements set to music: a few fights such as the one between Prospero and Sycorax, a few magical light shows, lots of music, but the most compelling set-piece in the early going was the hide-and-seek game between Caliban and Miranda that circled round and round her distracted father. Watching them, you knew what was going to happen — the water-soaked bodies, jumping, rolling, and leaping really could only lead one place, even if you didn’t remember the play’s backstory — but still, watching the game shift by degrees from chase to catch to run away and finally all the way to sexual assault was sadly inevitable. It never became overtly violent, though Prospero did lock Caliban in his cell when he interrupted the game. But clearly something was wakening — and then the Italians came.

The restructured narrative meant that the shipwreck that opens Shakespeare’s play became a mid-production high point for Synetic, with a disorganized chaos of new characters spilling and splashing their ways onto the stage, kicking water high into the air, miming maritime labor, and generally having a great time. I’m always disappointed with productions of the Tempest’s shipwreck — it’s my favorite scene anywhere in Shakespeare, but so hard to get right on stage. But this show, with no words and even no Boatswain, got to the scene’s disorderly heart. This kind of fracturing is what happens when ships break and bodies get wet. The old rules about weather and politics and fathers and magic and theater start to pull apart. “We split, we split, we split!” — as no one said during this production.

I won’t say that the show went downhill from there, but as the familiar scenes flowed by, the performances were great but never really got back to the intensity and high-jinx of the wreck. For me, at least, that was the slipper top. How do you beat immersion? (By this time I was thoroughly soaked and grinning.)

Some smart stage bits followed, including a touching scene in which Miranda shows up with a set of keys to unlock Caliban’s cell — is all forgiven? — but then drops them in the water when Ferdinand strolls by. It turns out that Caliban didn’t need the keys, because the cell wasn’t really locked. The scene set up the orphan’s flight into the arms of a wonderfully drunken and later cross-dressed Stephano.

There were some interesting changes in casting — both Trinculo and Antonia were played as women, which added sexual tension to the drunkards’ reunion and seductive force to the usurpation of Milan. The performance of Ariel by Don Istrate was brilliant, playful and ice-hard at the same time, shimmering in silver body paint.

Perhaps because we’d seen him young and alone, struggling to care for his infant and ambushed by Sycorax, this Prospero was unusually sympathetic and non-tyrannical. In the end, his drowning of book and staff (no place to bury anything on this stage) was elegiac rather than terrifying. I thought about Ovid’s Medea, but didn’t really see much of her.

The magic book itself, which looked like nothing so much as a waterproof MacBook in one of those faux-folio cases, ended up in Caliban’s hands as the ship rowed away. He gazed into its luminous pages, a hopeful, wistful expression on his face. Did he see something? No. Then the lights went down quickly, leaving him alone in the dark.

A great, wet, exuberant show, with a touch of sadness at curtain. It’s amazing what water can do, even now that it’s become almost a stage cliche — though I’ve never seen anything as fully immersed as this show before. The run closes March 24, and it’s quite silly for me to even think about a second trip to DC in that time, especially since I’ll be back in early April for an eco-event at MEMSI. But it’s tempting.

If you’re in or near DC before then, go. And sit in the Splash Zone.