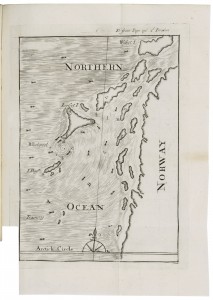

I’m thinking about whirlpools.

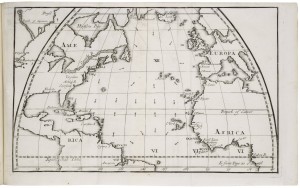

Specifically the Maelstrom off the coast of Norway but also whirlpools in general. These fairly regular features of the supposedly featureless ocean arise from the interactions of powerful tidal currents around narrow channels. They’re a bit like tidal bores, which show up in rivers and estuaries and feature in a wonderful scene in Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies.

Here’s an early modern image of the Maelstrom  —

—

I’m wondering if this oceanic feature can partially displace the beach as our primary physical symbol for land-sea interaction?

Whirlpools, like beaches, get formed when the sea & land come crashing towards each other. Both are structured by tide and time, both are fairly predictable, but mathematically complex. Neither was well understood in the early modern period. The downward force of maelstroms, as Poe reminds us, asks us to think of them as descents into the ocean rather than movements towards land. Homer’s whirlpool has a monster inside it.

Thinking of whirlpools or maelstroms as oceanic forms, features that are in their way as typical of land-sea interaction as the beach or other contact zones helps shift us imaginatively off-shore without entirely forsaking land for deep water. The whirlpool is an inhuman and inhospitable place, but it’s still created by land, at least in part. It’s not a human contact zone like a beach or a ship, but it’s a site of interaction.

Despite Poe and Jules Verne, coastal maelstroms aren’t strong enough to suck down ships or submarines. But what if we think of them as windows into the ocean?

These thoughts are all leading up to the Oceanic Shakespeares SAA seminar early next month, where all such questions will be resolved.