What would it feel like to rule the world? To believe that your own ordinary embodied body lay atop of history’s moving current, guiding the flow of revolution, so that everything that happens, happens to you, because of you, through you, in relation to you? What if you believed you were the apex of every pyramid?

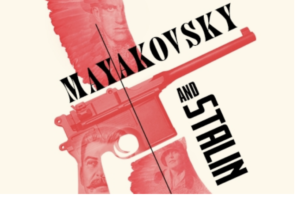

It can’t be easy to keep the vast swirl of history flattened inside one single faraway gaze, one commanding posture, and one pair of slightly inward-turned boots. Maury Sterling’s performance of Stalin, on stage for the next month in the gorgeous Cherry Lane Theatre in the West Village, wears glacial white and speaks about the revolution, as Max Faugno’s Chorus tells us, as a “sincere intellectual.” What struck me most forcefully from this performance of one of the last century’s greatest monsters was Stalin’s calm solidity, his eerie stability in speech and in silence. No extra movement from the Man of Steel. In Murry Mednick‘s play about the Communist dictator and the revolutionary poet Mayakovsky, who Stalin never met but whose reputation received the dictator’s posthumous benediction, Stalin commands everyone — except his wife Nadya, played with coiled-spring energy by Jennifer Cannon, who eludes him finally through suicide.

The play features twinned suicides, of Nadya in 1932 and of Mayakovsky in 1930, which loosely connect the two plots of political and poetic revolution. The play bounces the paired narratives off each other, contrasting Stalin’s mastery with Mayakovsky’s somewhat floppy enthusiasm, his declamatory poetry, and his “bad teeth.”

What does the revolutionary poet who died young say to the dictator who bent Eurasia to his will? Mednick’s play makes explicit connections between the fervor of revolutionary Russia and his own ferment in the American 1960s, when he collaborated with Sam Shepherd and Ed Harris. I also wondered about the resonance of the Brik family, who embraced Mayakovsky and his revolution, but whose wiser sister Elsa, played with precise energy by Alexis Sterling, left the Soviet Union for a distinguished literary career in France, where she was also part of the Resistance.

Mayakovsky and Stalin is complex, verbally dense theater. For my fellow Shakespeareans, I caught echoes of the second half of Macbeth in the fractured post-triumph marriage of Stalin and Nadya. I also enjoyed the explicit Lear allusions in the language of “nothing” and in Mayakovsky’s fart jokes. “Blow, winds,” &c.

I spend a decent amount of my time sitting in the front row of intense, demanding plays like this one. In fact, a month ago I was in almost the same seat for Keith Hamilton Cobb’s brilliant American Moor, also at Cherry Lane. Mayakovsky and Stalin wasn’t my usual Shakespeare or Shakespeare-adjacent fare, though I’d gotten a revolutionary Soviet art warm-up through Peter Brook’s Why? at Tfana, which also touched on Maykovsky. But for me the added strangeness and wonder of this show was that two of the eight actors, Maury and Alexis Sterling, are my brother- and sister-in-law. Instead of flying solo to the play as I often do, I sat last Saturday on opening night surrounded by family. A noisy party of grandparents, cousins, and in-laws from both coasts of America and both sides of the Atlantic gathered together after the show for Georgian food (not the American Georgia but the European nation in which Stalin was born) down the street.

It’s a treat to be part of a family that makes great art, and great gatherings. I’m going to go back before the run is over on Nov 10 — and you should too!