I just sent off to Shakespeare Bulletin two mini-reviews of my favorite moments in Shakespearean performance of the past decade. The first was of the opening scene of a Lear at the Shakespeare Theatre in DC from 2009, and the second the closing scene of the Propeller Winter’s Tale at BAM in 2005. Here’s the first —

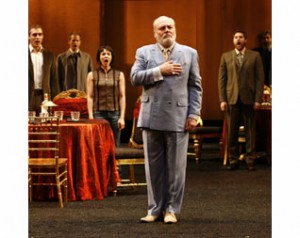

We don’t usually picture big, powerful, ponderous, regal old men dancing in public. Perhaps it’s imaginable as a careful, discreet display. But when Stacy Keach as Lear high-stepped his way onto the stage in the opening moments of this production, accompanied by a brass band and hurriedly-assembling dance line, he gave a shocking display of theatrical power and audacity. The old King’s body staked its claim to center stage physically, forcing his way through the party-goers who crowded around in the decadent, faux-Balkan nightclub setting. This was a Lear who could still dance, who still wanted to display physical power and virtuosity – the legs kicking up well over waist-high – and who still wanted to play the part of youth. For that moment, as the King came onto the stage, I saw something renewed in this familiar play: a sharper contrast between age and youth, and a new the irony in the purported desire to “unburthened crawl toward death.” The reviews at the time mostly talked about the Balkan setting and post-Yugoslav mafia staging in Robert Falls’s violent production, including a long abstract scene in which cloth-wrapped bodies of the victims of the kingdom’s wars were slowly lowered into an on-stage pit. For me the defining moment was at the start, when the King showed off his still-powerful body, his flair, and his belief that he still owned the world. The bad daughters and courtiers fawned on him, and the good girl, played in black as Goth hipster, retreated in horror at his poor taste. More than anything, Keach’s body made palpable the King’s protest against time. We in the audience knew that his dancing body will be buffeted by inner and outer storms for the next three agonizing hours. But the high, physical, lusty steps managed to create a power beyond age, at least for a stage instant.

The seated crowd and partying lackeys weren’t the only audience to whom the King was playing in this moment. Above his head, in a massive gold frame, was a portrait of himself, in full royal regalia, at a younger age. The contrast between the benevolent, happy monarch who stares down from on high and the charismatic performer strutting below provided a visual touchstone for the play: this old King can never live up to his younger self. We usually have to wait for Cordelia’s “nothing” to split Lear apart. In this production, his internal divisions get shown immediately and viscerally.

There were lots of things that didn’t quite work in this high-concept production, and I don’t quite rank Keach among the very top performers of this Lear-filled decade. But it was probably the best stage entrance I’ve ever seen.

What follows resurrection? The statue has come back to life, the King and Queen reconciled, the two kingdoms resumed their amity, and royal authority even re-constituted so far as to make up a final faux-comic resolution via the marriage of Camillo and Paulina. What’s left? An awkward pause, perhaps, as the wave of comic unity floats everyone ashore, before Leontes leads away and we can start clapping.

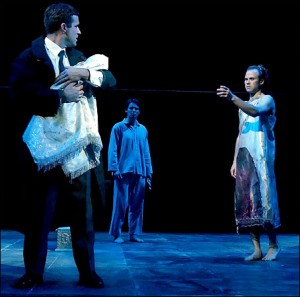

Not this time. Propeller’s version of “The Winter’s Tale” featured the company’s usual high-jinx, including full brass band numbers for Autolycus’s songs and men in all the female roles, among them the brilliant Simon Scardifield, whose work I’ve greatly missed in Propeller’s recent productions, as Hermione. This production greatly increased the visibility of Mamillius, who, played by Tam Williams, who later doubled as Perdita, provided a visual through-line in the convoluted story. In the Sicilian half, he’s everywhere, starting the play alone onstage, listening at doors, playing in corners, watching his father rage and his mother sent to prison. His toy ship got used to represent his sister’s voyage to coastal Bohemia, and his toy bear eats Antigonus. The boy who told his mother and her ladies that “a sad tale’s best for winter” became in this production the central figure of narrative continuity within ever-shifting terrain.

He came back, finally, as a ghost. In a shocking, wordless coda to the performance, the boy Mamillius re-appeared holding a candle after the royal parties cleared the stage for the last time. His father saw him and returned, his face fractured into disbelief and unlooked-for hope. As the lights started to dim, Leontes circled across the stage toward the boy, slowly opening his arms for a redemptive embrace. The King cast a grotesque, large shadow onto the empty stage behind him, looking from where I sat in the balcony like a gigantic bird, spreading wings and opening talons. Mamillius had his back to the audience, and we could not see his face. He kept staring at the candle cupped in his hand as his father awkwardly moved downstage toward him. At the last minute, he looked up at the twisted face straining down at him, and blew out the candle.

Some might think that we shouldn’t cry at the end of this play, but we did. The play’s loss and disruption flooded out over the shocked audience. I’ve never felt more palpably the cost of this play’s wayward tale of reunification. It’s always hard to trust Leontes, who’s too eager to sweep his earlier transgressions under the rug, but it took this stage gambit to make visible the tragic undercurrent for all to see.

I attended that STC Lear with my son, and you’ve reminded me how powerful it was at times. There were other moments that were TOO much, but another scene that stays with me was the death of the clown: it happens on stage, for once, and was well done — he reclines, dies, is taken away, yet another body.

That was also a strong moment, though I never thought we got all the way back to the fantasia of the opening moment. The bodies in the pit was a powerful staging of anonymity, which I suppose has a textual basis (“poor naked wretches”), but strained against the family story, at least for me. Btw, they also killed the Fool on stage – via a 40′ noose — in the McKellan Lear, which I guess didn’t get to DC?