In Donmar Warehouse’s all-female Shakespeare Trilogy, directed by Phyllida Lloyd and starring Harriet Walter, the set has always been the same: a women’s prison. Before each performance, a siren sounded in the lobby and then the cast, shackled and in grey prison sweats, was marched through the crowd under the watchful eyes of uniformed guards as well as audience members. In Julius Caesar in 2013, guards and inmates snarled at each other. In Henry IV in 2015, Hal’s pre-show announcement — “I’m gettin’ out!” — set a trap that finally snapped shut with Falstaff’s show-ending wail to the now-king, “Don’t you fucking leave me!” In both cases, the shows were brilliant as performances of Shakespeare, but they also played compellingly with the prisonhouse exterior.

In Donmar Warehouse’s all-female Shakespeare Trilogy, directed by Phyllida Lloyd and starring Harriet Walter, the set has always been the same: a women’s prison. Before each performance, a siren sounded in the lobby and then the cast, shackled and in grey prison sweats, was marched through the crowd under the watchful eyes of uniformed guards as well as audience members. In Julius Caesar in 2013, guards and inmates snarled at each other. In Henry IV in 2015, Hal’s pre-show announcement — “I’m gettin’ out!” — set a trap that finally snapped shut with Falstaff’s show-ending wail to the now-king, “Don’t you fucking leave me!” In both cases, the shows were brilliant as performances of Shakespeare, but they also played compellingly with the prisonhouse exterior.

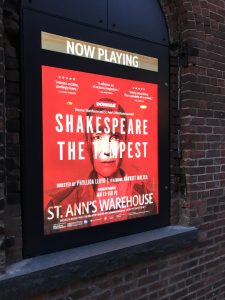

Last in the trio comes The Tempest. The drama of forgiveness and reconciliation lacks the angry critique of male egotism and violence that served as spine for the previous two war stories. But the play’s language of bondage and liberation, shared by Prospero, Ariel, Caliban, and Miranda, as well as the Italian castaways, resonated in the setting. Even more consistently than the previous two shows in the trilogy, this Tempest repeatedly emphasized the extra-Shakespearean identities of the inmates. Thus Harriet Walter’s Prospero was also the “prison character” Hannah, who was in turn (according to an insert in the playbill) based on the true story of Judy Clark, a onetime member of the Weather Underground who has been in prison in New York State since 1983. The prison-story toggled back and forth with the Tempest-story, with guards helping with scene changes and requiring, for example, that the Neapolitan aristocrats change from regal to prison garb.

There was a lot to like about this production, much of it centering around the brilliance of Jade Anouka, who also stole the show as Hotspur in Henry IV. Playing Ariel this time, as well as (at least the night I saw it) one of the prison guards, she (as it were) “flamed amazement.” Dancing, singing, rapping, teasing Prospero and mocking the castaways, the spirit dominated the stage. Working with music by Joan Armatrading, Anouka represented the heart of what I liked most about this Tempest and the whole trilogy: the whirling energy and relentless drive of the staging, acting, and production. As she said of her storm and her performance: “Jove’s lightning, the precursors / O’th’ dreadful thunderclaps, more momentary / And sight-outrunning were not!”

Anouka’s performance wasn’t the only theatrical highlight of the evening. The lovers were much better than they sometimes can be, energetic as well as sweet, with a slightly goofy loose-limbed enthusiastic performance as Ferdinand by Sheila Atim and a wonderfully lively Miranda by Leah Harvey. Pouting when her father made her beautiful prince carry those boring heavy logs (or, in this case, the recycling), Miranda’s teenage rebellion and eagerness recalled in happier terms the scene in Henry IV when the sullen teenage prince Hal put on dark glasses and Beats so he could ignore his father’s war council. Sophie Stanton’s Caliban was also wonderfully funny and engaging, if perhaps lacking a bit of the bite of her Falstaff in 2015.

Many reviewers, including Ben Brantley in the Times, who called this production the “most entertaining Tempest I’ve ever seen,” loved Harriet Walter’s Prospero more than I did. Her performance only really moved me once, when she punctuated “Our revels now are ended” by running around the stage popping the dozen or so huge balloons onto which a cheesy vacation-masque montage had just been projected. Searching for the last balloon to pop, ranging about the stage amid startled actors, she hit the familiar lines with real fire: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on, and our little life / Is rounded with a sleep.” Pop!

I kept thinking about the magic island as a prison, and wondering how that meshed with the play’s utopian lyricism, in Gonzalo’s rehashing of Montaigne’s fantasia about the cannibals of Brazil and Caliban’s “sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.” I was also thinking about the harsh force of the end of Henry IV, in which Hal but not Falstaff got out of jail.

The last turn of the stage-prison surprised me, in a good way. I’m still thinking about what it means. Prospero, once again in the prison character of Hannah, was the one left behind. All the other inmates waved to her from the stage doors on top of the bleachers. She has drowned her book of spells in a plastic garbage bag, but has a paperback to read, Margaret Atwood’s, Hag-Seed, a brand-new revision of The Tempest. Alone, she sat on a bare cot on a bare stage. With Ariel, Miranda, and the others all gone, her island lacked magic and music.

Not all wizards escape.

Leave a Reply