A piece of it snapped into place on Saturday morning when I had snuck away from the Hyatt, quite far from the conference panels. As the merry shaxsters professed and queried, my little bark was bouncing into the white-capped mouth of the St. John’s river, heading back into a sharp west wind after a chilly morning’s offshore fishing with my Dad. That’s when I figured out how to make sense of the ghostly sensations of #shax2022. We shax-ers are used to being the melancholy prince, the one who knows the secrets and critiques the actors, who interrogates audiences, plays with pirates, torments innocent young women, and doesn’t understand his mother. The star among stars, that piece of work, machine, vehicle, corpse.

But what if we’re not that one, nor were meant to be? I think that one of our absent colleagues got the story right in a tweet from Irish post-RSA Covid-jail – this year especially, we’re the Ghost. Remember me? What if the revenant’s plea is more desperate hope than paternal order? Remember the SAA? The way it used to be? The way we maybe kinda want it to be again?

Well, here’s the truth, at least as I feel it from home the next day – my beloved conference, the one I grew up in as an academic, isn’t the same thing, anymore – but it’s still a pretty good thing. Change disrupts us all, but, even though neither of the boys Hammie ever manage to figure it out, change isn’t only for the worse. The spectral feeling of #shax2022, with ghosts tweeting in from Dublin, Buffalo, LA, Wittenberg, Atlanta, and other places – all these things might yet resolve themselves into a trajectory that’s more sea coast of Bohemia than dreary old Elsinore. Or at least that what I’m hoping, as I tap out this blogdraft on my laptop homeward bound at the airport while the rest of the conference gets ready for the 50th anniversary dance.

Mulling my usual bloggy recap reminds me that, after two years chock-full of Zoomtopian adventures, in-person conferencing feels exhausting and overflowing. I loved the panels and seminars that I was able to catch, I was energized and pleased by how well the seminar I organized and chaired, #s31 “Rethinking the Early Modern Literary Caribbean” went on Friday morning, and I’ll say some things about all these more or less official bits of content in due course. But by far the best parts were the unpredictable joys of in-person ness, the Brownian motion (named for the botanist Robert Brown, but I know we’re all thinking Urn Burial) of the assorted receptions, the chromatic cornucopia of even this year’s smaller than usual book exhibit – that’s the stuff that’s hard to get on the small screen. I was happy to be back in it.

I don’t want to minimize the risks of having this kind of event during a global pandemic, and although I was happy to mask up indoors, I don’t think we should be under any illusions that we weren’t engaging in some virus-supporting behaviors. I lost a seminar participant to the RSA variant, and although I tried to Zoom him into the room at SAA, it didn’t work. Hybrid conferencing is hard, expensive, and perhaps in the current reality not fully operative – but I also hope that we can keep speculating our way toward more accessible and inclusive events, even if it’s not clear how all those things can be balanced equitably and practically.

[A parenthetical note – I know many people were upset bc Thursday’s reception was moved inside, an objectively riskier setting. The violent thunderstorm that soaked the outdoor venue around 4:30 was pretty much as predicted, but the truth is – as the staff at the Hyatt knows well – those sorts of storms punctuate spring and summer afternoons in north Florida, which my seminar would include inside an extended Caribbean region. I would have preferred to be outside too, and I regret excluding those who weren’t comfortable with indoor wine chats. But even in our Anthropocene context in which even the weather is “our fault” on some level, I’m not sure we can pin this one on the SAA-powers that be. So foul and fair a day, &c.]

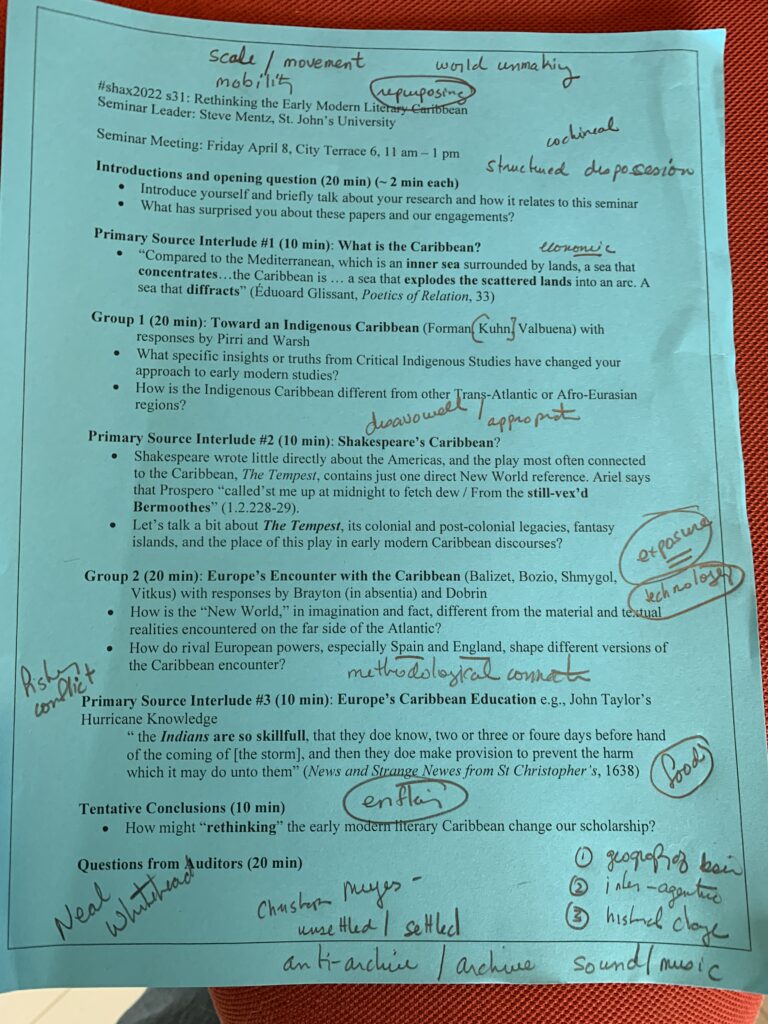

I had a typically ornate triple-barreled intro to my seminar on Friday morning, and I’ll re-purpose it here as a “lessons from #Shax2020” frame before chatting about things I learned from my brilliant colleagues throughout my days at the conference. I started my seminar with three quick contexts for my seminar and maybe the whole gathering —

- I opened by calling attention to the Indigenous Timucuan people, who stewarded these lands and waters for many generations. While lacking knowledge or expertise myself, despite having family living in greater Jacksonville, and while also aware that the super-fast “land acknowledgement” can be pretty thin beer – I wanted to pronounce (or maybe mispronounce) the word “Timucuan,” as a prompt to memory, and as something that deserves more of our time and attention.

- I also opened my seminar by talking about the weather – to emphasize the Caribbean context of the unsettled, violent, and sudden storms we saw on Friday, and also the sudden drop in temperature on Saturday. We talked a fair amount about the long reach of the Caribbean in the seminar – New Orleans and Jax are definitely Caribbean locales, but what about Virginia? Bermuda? An octopus-armed region started to take shape in our conversations…

- I also recalled the early modern colonial settler history of the Jacksonville area, including Fort Caroline, the 16c French Huguenot settlement that I brought a few of my early-arriving seminar members to the site of on Wednesday afternoon, and also, about 40 miles to the south, the city of St. Augustine, settled by the Spanish in 1565, which proudly proclaims itself the oldest European settlement in the United States. As one of my seminar participants recalled in the context of Puerto Rico, the long history of Anglo colonization of this region isn’t only in the past.

Also one more thing about my seminar – I was so amazed by and grateful for the contributions of my two non-Shakespeare invited participants, early modern historian Molly Warsh and blue ecologist Sid Dobrin. Having their breadth of expertise and alternative perspectives in the room challenged us to think beyond literary narrowness – plus I felt so lucky to share their company and good humor throughout the conference.

More non-Shax guests at SAA, please!

And if you’ve not read Molly’s amazing study of the 16c pearl industry in the Americas, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, or Sid’s Blue Ecocriticism and the Oceanic Imperative — read them, soon! I hope you learn as much from them as I have.

So — enough about my seminar! What about everyone else’s presentations?

I loved the hybrid seminar that Hillary Eklund and Debapriya Sarkar (with help in absentia from Ayanna Thompson) ran, which explored how we might meaningfully connect recent work on premodern critical race studies and ecocriticism. This seminar ran in parallel with an online seminar on Wed that I missed, and both were also, in a sense, sequels of the stunning Zoom panel that Hillary, Debapriya, Ayanna, and Kim Hall ran in 2021. I’m not sure anything can top the “Becoming Undisciplined” linked presentations in 2021 for imagination and style, and in some ways it was perfectly appropriate, if incongruous, that I listened to that session in my earbuds while tromping the squishy woods of Connecticut in mud season. Some parts of that strangeness fell away this year in the Hyatt’s conference room. The 2022 in-person seminar was brilliant, and featured the work of many people I admire greatly and others who I’m looking forward to learning more about. Ayanna’s remote response asked how “elastic” a category we want race to be. I wondered the same thing about “ecology,” which can often be deployed as metaphor without much matter. Maybe the Venn diagram overlap of these two expandable methodological terms is not the thing we need to find? Maybe instead we might seek the value of shifting across and between race and eco-thinking? It also occured to me as I listened to this seminar’s patient explorations that identities and communities always shape how each of us as individual scholars and humans can (or should) explore ideas. I can’t think about premodern critical race studies without being a white suburban ecotheorist who loves water and wild places, even as I at least try to recognize how access to the watery practices that I love and that have shaped me have themselves been so distorted by racist histories in modern America and elsewhere.

The conversation got pretty meta in the prcs/eco seminar, and it was a jolt to dive next into the technical waters of the panel on Shakespeare’s Editors, organized by Claire Bourne and Molly Yarn. In the seminar there had been some perfectly justified grumbling about excesses of Shax-centrism, and some wondering if we had to drag old bald Will with us everywhere we go. The turn from the broad political urgencies of environmentalism and racial justice to the close-in labors of, to take the first paper, female textual editors who published Malone Society editions between the wars in England, could have felt like a narrowing. But – and maybe this was the moment that I remembered that I am, for better or not, very deeply a Shakespearean – by going through those editorial technicalities with this panel, digging into those Malone Society manuscripts, John Milton’s (!) copy of Shakespeare, and, in a final paper that I found deeply moving, the very 1964 Signet Classics edition of Shakespeare’s sonnets that I read in high school around 1980, the panel ended up with some powerful conclusions about the legacies of misogyny and homophobia both inside and beyond academic culture. The political edge of these papers came somewhat indirectly – a key, and utterly devastating, point in the final paper asked us to read the absence of notes to one of the young man sonnets as evidence of things that could not be said during the Lavender Scare years – but not the less powerful because of their indirection.

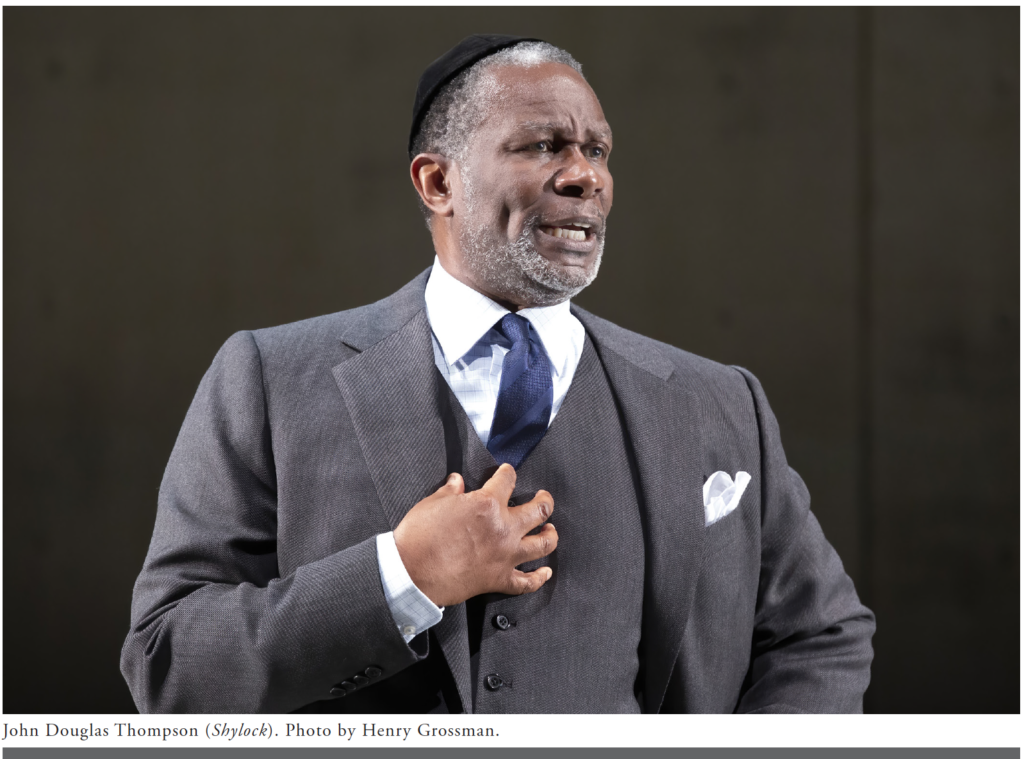

The panel that to a substantial extent married the political ambition of the prcs/eco seminar and the literary precision of the panel on editing was the Plenary, which featured Ruben Espinosa, Lisa Barksdale-Shaw, and incoming SAA president Ian Smith speaking about the past fifty years of critical race studies in Shakespeare. Ruben opened with a moving and personal evocation of how he came to Shakespeare and how the Anglo- and Shax-worlds present both borders and bridges. Lisa followed with a complex entanglement of trauma theory, Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, and current neurological understandings of how trauma changes the brain. But the barn-burner, delivered without slides and from a calm, seated posture, was Ian’s extraordinary argument that “rugged Pyrrhus, he whose sabled arms / Black as his purpose, did the Night resemble” (Hamlet 2.2) might in fact be…Black. For an audience that has collectively been learning to see race in Shakespeare, not least from Kim Hall, Ayanna Thompson, Margo Hendricks, and the other #raceb4race luminaries whose names and arguments were often cited in this panel and elsewhere, Ian’s talk was an amazing display of asking us to read carefully the thing we’ve not seen that has been under our noses all this time. What is Blackness in Hamlet? Not just the prince’s “customary suits of solemn black” (1.3)!

What struck me most powerfully from Ian’s resonant talk was its close, patient, formal (even formalist?) insistence on attending to things in our most famous text that we’ve been reluctant (or unable, or unwilling) to recognize. For the son of Achilles, dripping with blood and hot for revenge, to be Black reanimates the color-language of this hyper-canonical play, and perhaps that reanimation might also extend to some larger questions surrounding western Europe’s legacies from the Eastern world of Homer’s Troy. Perhaps because it followed Ruben’s personal honesty and Lisa’s ambitious synthesis, Ian’s talk engaged politics through that most traditional and fundamental act of literary practice – just read the text, and follow where it leads. I’m always stunned, and elated, by how endlessly generative this most basic act of literary analysis can still be.

Which is why, I guess, even though I was a plane during the dance, missed the Saturday morning talks to go fishing, wasn’t there for the 50th anniversary toast, and even skipped the terrific early Friday line-up for a pre-seminar swim — I still find my ghostly self in my community at SAA. Even old Will may have some kicks left in him. He’s got lots of problems and contains corrupts legacies, as of course I also do myself. It’s our job to surface these truths. But there are still multitudes, more than dreamt in our philosophies.

It might be a bit chilly in Minneapolis in 2023, in the cruel month of April. But I can’t imagine I’ll be able to stay away!

Thanks to everyone who I saw, the many more who I missed, and people following remotely. It was great to conference with you again!