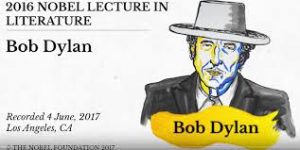

Just a few days ahead of the June 10 deadline for collecting the Nobel Prize (and its prize money), Dylan fulfilled the only requirement by recording a 4000 word / 27 minute variation on the theme of a laureate lecture. He Dylans the whole thing pretty hard, especially on the gravel-voiced recording, backed by solo jazz piano. Is the music a nod to his most recent albums of Sinatra-era standards? It’s hard to know with Bob.

Just a few days ahead of the June 10 deadline for collecting the Nobel Prize (and its prize money), Dylan fulfilled the only requirement by recording a 4000 word / 27 minute variation on the theme of a laureate lecture. He Dylans the whole thing pretty hard, especially on the gravel-voiced recording, backed by solo jazz piano. Is the music a nod to his most recent albums of Sinatra-era standards? It’s hard to know with Bob.

The core of the talk features plot summaries of Moby-Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, and The Odyssey. They have have a book-report-ish air about them, and he implausibly claims that he read all three in “grammar school,” along with Don Quixote, Ivanhoe, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels, and A Tale of Two Cities. They kept those kids busy in the Iron Range!

I think the point of the plots is co-opting by summary: the singer’s job, Bob almost says, is to restyle old stories, to circulate them and celebrate them. It’s a compelling argument against originality, made with typically unmistakable obliquity.

I like to read Dylan by flashes of lightning, so I’m going to dish out some slices and see what adds up to —

Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story.

He ends where Homer begins, with an explicit donning of the poet’s mantle. The more I think about it, the more the whole lecture sounds like Dylan handling the literary canon the way Renaissance humanists say that a mother bear licks her infant cubs into their bear-shapes, forming their bodies into new shapes with love and saliva. The last section of The Odyssey that Bob picks up to play with describes the meeting of Odysseus and Achilles in the underworld, and Achilles’s wish to be “a lowly slave or a peasant farmer on Earth rather than be what he is — a king in the land of the dead.” Sounds as if he’s not interested in epic directness and loss, but romance’s circuity and weave.

When I first received the Nobel Prize for Literature, I got to wondering exactly how my songs related to literature.

It’s usually a mistake to take him at his word, but I can’t help feeling that he’s seriously interested in the question that launched a thousand web takes back when the Prize was first announced. What is the relationship of songs to literature? What message did the Swedish Academy want to make picking Dylan in October 2016?

Everything is mixed in.

He’s partway through his half-step summary of Melville when he gets to this one, but all of a sudden the floodgates of wonder-world swing open. Isn’t all art about only and obsessively mixing? Might Bob know this better than most? A serial plagiarist, the most widely generative writer of his generation, and a still-obsessed practitioner of the communal art of live performance in his late 70s — who better than Bob to name art’s heterogeneity while retelling for us that old story about the white whale?

There’s two roads to take, and they’re both bad.

Here he’s on the road with Odysseus, taking us along for the long ride. And just when we reach for the interpreter’s hatchet, he jumps out ahead. “In a lot of ways,” he rambles, “some of these same things have happened to you.” He’s not the wanderer, he insists. You are.

I don’t know what it means either. But it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good.

This one’s in response to an aside in which he out-of-contexts a couplet from “poet-priest” John Donne. What I like is the attention to sound, including Donne’s rhymed couplets and the slow-jazz piano in the background of the audio recording. Perhaps meaning isn’t the main thing?

You know what it’s all about. Takin’ the pistol out and puttin’ in back in your pocket. Whippin’ your way through traffic, talkin’ in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You’ve seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades have been wrapped in white linen.

These aren’t only Bob’s stories, and I’ll admit I’m a sucker for this kind of American mythology, this Wild West-ing of story and tall tales that provide a kind of demotic and democratic undersong to the literary canon of Melville and Homer. This stuff, Bob’s insinuating, belongs next to the other stuff, up on the same prized shelf.

Our songs are alive in the land of the living.

Or maybe he doesn’t want to put any of these songs or stories up on any shelf. Maybe he’d rather take them out of the underworld-library and sing them, night after night, in a tattered old man’s voice. “They’re meant to be sung, not read,” he says. I thought about that bifurcation a lot this past spring semester, when my Intro to Literary Theory class started off day one listening to a younger Bob croon, “Won’t You Please Crawl Out Your Window,” which I explained as an image of the theory’s gambit. Each week we’d start classes by reading or listening to a “Weekly Bob” song, paired with “Weekly Emily” poems. Sometimes we wrestled with the language. Other times we listened to recordings. We discussed the early-form video of Subterreanean Homesick Blues. I’m not sure if we ever figured out whether it was better to read or listen, or how many of my students thought Bob was just old white-guy professor music anyway.

Read it if you can.

He says this last one about Moby-Dick. But it’s not only about Moby-Dick.