Four weeks from today eco-voices will fill the Folger’s Foulke Conference Room as Creating Nature begins. I’m looking forward to hearing from the many brilliant people who will be joining us in May. (Click the link for more!) Over the next several weeks, I’ll do some long-distance introductions of the four sessions and the plenary lecture with special attention to something very specific that I hope will emerge from our conversations: a practical interdisciplinary lexicon for environmental thinking.

In asking for a lexicon, I’m emphasizing that we come to this conference with different critical and professional vocabularies, but I hope we’ll leave it with some new terms, new ideas, and new ways of thinking. The title, “Creating Nature,” is a line from Shakespeare (Winter’s Tale 4.4), but also a provocation to think about how we create the nature that creates us. That’s why the conference will bring together not only active researchers in the premodern environmental humanities but also scientists, anthropologists, artists, and environmental lawyers. Knowing that it’s not fair for each of these figures to represent fully their rich and complex disciplines, and recognizing that many of us, especially the Shakespeare scholars, may tend to revert to type in our beloved Folger’s halls, I want to introduce the conversational challenge faced by each of the four panels and the interdisciplinary plenary. How can we best talk to and with each other? What words do we need, and how can we use them?

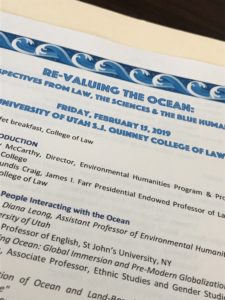

The first morning’s session on “Sustenance” will be chaired by eco-Shakespearean Karen Raber and feature talks by maritime environmental law scholar Robin Kundis Craig, environmental historian Dagomar Degroot, and Shakespearean Julian Yates. Their challenge will be to weave together Robin’s analysis of “Saltwater Sustenance” with Dagomar’s excavation of the “Frigid Golden Age” of the Dutch Republic during the Little Ice Age with Julian’s analysis of food, cooking, and other cultural activities in and beyond Shakespeare, perhaps all the way to Noah’s Ark(ive).

I won’t step on what I anticipate will be a stimulating and imaginative session, but I’ll speculate a bit about sustenance and food in terms of a critical lexicon. There’s lots of great scholarship on food today, from the Early Modern Recipes Online Collective co-run by Creating Nature-ers Rebecca Laroche and Jen Munroe, among others, to my St. John’s colleague Steven Alvarez’s amazing “taco literacy” scholarship and teaching that ranges from Mexico to Kentucky to Queens. In advance of our symposium, I’m thinking about food as comprised of material, cultural, and spiritual objects and processes. I’m thinking also about a moment in New Jersey many years ago, when after attending the funeral of my ninety-four year old grandmother, I ranged through the back of the fridge to extract and wolf down the week-old leftovers of a lifetime’s worth of her special potato pancakes. The pancake I ate was stale, cold, slightly rancid, and painfully delicious. I can taste it still, and not just when I get up early on a holiday morning to struggle through my approximation of her recipe for my own children.

More soon, about “Storms,” history, and paleoclimatology!

Arcadia’s got the beat. “Habemvs Percvssio,” the inscribed arch proclaims in the opening number of Broadway’s only current musical based on an Elizabethan prose romance. The show starts with the most famous of the many Go-Go’s numbers that make up the musical backstory. “

Arcadia’s got the beat. “Habemvs Percvssio,” the inscribed arch proclaims in the opening number of Broadway’s only current musical based on an Elizabethan prose romance. The show starts with the most famous of the many Go-Go’s numbers that make up the musical backstory. “