So many pleasures at SAA, and so many lingering, insinuating questions. As I was leaving, the music of an imaginary Q&A echoed in my head. I wonder if anyone else heard it? A gentle espirit d’escalier that drapes itself over tired professorial shoulders and sounds in imagination-crammed ears, as we’re waiting to board homeward-bound jets?

So many pleasures at SAA, and so many lingering, insinuating questions. As I was leaving, the music of an imaginary Q&A echoed in my head. I wonder if anyone else heard it? A gentle espirit d’escalier that drapes itself over tired professorial shoulders and sounds in imagination-crammed ears, as we’re waiting to board homeward-bound jets?

Still-audible voices wafted me home through crowded planes and airports.

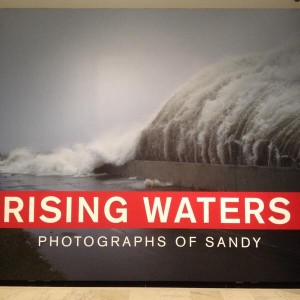

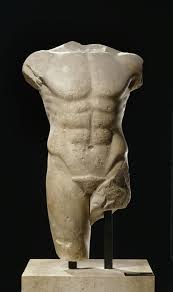

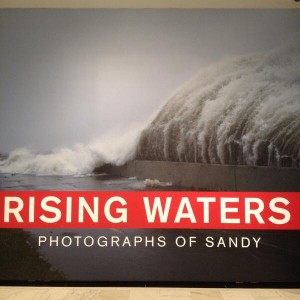

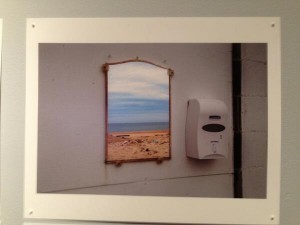

In retrospect, I was a bit jumpy this year. The paper session I organized on “Catastrophic Ecologies” is near to my heart as well as my academic work, and I wanted people to like it. My visual aid, a slideshow of pictures of New York City and my neighborhood in Connecticut during Hurricanes Sandy and Irene, trespassed somewhat on academic decorum. I wanted the images to comprise a parallel text of catastrophic aesthetics alongside my reading of Antony and Cleopatra. The slideshow rolled through its forty-odd pictures five or six times during the talk. I wonder how many audience members noticed that one picture was of me, in shorts and sandals, holding my dog in my arms? She’d run barking out of the house toward the flooded street at the end of Hurricane Irene, and I was carrying her home.

(In a can’t-make-it-up coincidence, the rescued dog’s name, Shanti, figured in Diana Henderson’s Presidential Address. She quoted the name from her primary poetic intertext, St. Louis native T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, which ends with the Sanskrit word for peace: shanti shanti shanti. That’s the poem from which we lifted the dog’s name – with the intended joke that a puppy brings love but not peace to a busy household, plus a happy near-pun on sea shanties.)

There was a lot of humanity amid the Shakespeare this year. Autobiographical musings filled the Plenary Session and Presidential Addresses, from erotic fantasies in (about?) the Folger vault to mayhem at MIT. The session on Shakespeare and the Humanities brought the Hegel harder that I expected, but I think it was seeking the human side of the human sciences, wanting to know what moves us. That’s what I want to know, too.

As always, I flew home chewing on what felt like a too-small slice of SAA. I missed most of the surging tide of Digital Humanities projects, though I did talk about some at the bar. I was taxi-ing to the airport during sessions on Auerbach and on Feminism, but the helpful #shakeass14 hashtag informed me that they featured human stories too. I hesitate to mention the brilliant scholar who fainted during her talk, except to say that in that shocking instant, our knowledge of the dependence of intellect on the physical body was frighteningly redoubled. Even Shakespeareans are human creatures, it turns out. (I’m relieved to say that she reported feeling much better an hour or so later.)

One of the best questions I got after the Flood talk was from a UCSB grad student named Chris Foley, who noted that my swimmer poetics, which puts little bodies into vast seas, emphasizes individual experience, possibly at the expense of human collectivity. That was the question I lingered over throughout the conference.

I’m not altogether sure you can have one without the other. Fleeting entanglements of individuals into and out of collectives make up the great Lucretian / Latourian dances of matter and of society. I want both!

I’m not altogether sure you can have one without the other. Fleeting entanglements of individuals into and out of collectives make up the great Lucretian / Latourian dances of matter and of society. I want both!

But the collectives I’ve been mulling are academic as much as ecological. There are few collectivity-making machines that I like more than SAA. Each year I rejoin a not-quite-the-same body of shared thinkers, teachers, and writers. Whatever niggling doubts I sometimes entertain about hyper-canonicity or Shakespeare exceptionalism – why not Middleton? Why not Nashe? — mostly vanish in a happy haze of cocktails and conversations.

I loved giving the Flood talk in the catastrophe collective. It was great to share the podium with Randall Martin’s humane exploration of gunpowder ecology in Macbeth, and to listen to Simon Palfrey bring the stylistic fireworks with his fictionalized fragments bursting out of the same play, voiced by Abigail Rokison and co-written with Ewan Fernie. One idea of the session – I wonder how well this sort of thing communicates across a crowded hall – was to push experimental forms within Shakespeare studies, and to splash around in atypical histories, images, and fictions. We wanted the difference-machine of ecological thinking to change our formal as well as analytical methods.

There was lots of meta-commentary at the conference around the shapes of our profession, past and present. Many people engaged a now-perennial debate: “We must historize, or…what did you say was our other option?” I wonder what an unapologetic pluralism might look like. Historicism is a powerful, indispensable archive and set of tools – but no single key unlocks the kingdom. Wanting to do things with Shakespeare in the world may require a willingness to be errant, to stray, to make discoveries.

SAA collectives are affective and intellectual, human bonds that assemble voluntarily (mostly) and disperse more or less the same way. Political action wasn’t my topic this year, but its imperatives demand attention.

The political questions that we academics must respond to today, it seems to me, are practical and institutional: redressing adjunctification, promoting equitable pay and stable employment, and reshaping humanities departments in a shifting cultural-economic landscape.

Some of my happiest moments at the conference came when I was talking with grad students. I heard a few job-related success stories, which amazing achievements are always welcome in the current climate, and talked about many great projects. The larger professional picture remains grim, but I find it hard to despair altogether about a profession that is helping to produce such smart, self-aware, sophisticated, resourceful thinkers. One task of those of us with stable jobs is to build systems worthy of such excellence inside and beyond the university.

I want a Shakespeare studies that might still speak with the dead but also addresses hurricanes and the squeeze of economic disenfranchisement. I want to confront these forces in varied languages that include the aesthetic, the performative, the overtly playful, and the utopian. Among many others!

I suppose it reveals my lack of activist fire that I turn invitations to rekindle the Marxist fire into experiments in form. I recognize that institutional problems require collective solutions, and I’m a happily paid-up member of both the faculty unions on my home campus. But at the end of the day, the force of Shakespeare (and even of Radical Tragedy) for me is aesthetic as well as political.

I suppose it reveals my lack of activist fire that I turn invitations to rekindle the Marxist fire into experiments in form. I recognize that institutional problems require collective solutions, and I’m a happily paid-up member of both the faculty unions on my home campus. But at the end of the day, the force of Shakespeare (and even of Radical Tragedy) for me is aesthetic as well as political.

I’m left recalling an odd departure, the peregrinations of the two-part “Object Oriented Environs” seminar led by Jeffrey Cohen and Julian Yates. (As usual, Jeffrey beat me to the blog.) After whipping their participants into a collective froth of intellectual ferment, with provocations provided by respondents Julia Lupton, Drew Daniel, Eileen Joy, and Vin Nardizzi, the seminar took a collective step back, paused, opened its doors (against SAA regulations, I believe), and took a short walk outside the room. Some participants rode the escalators up and down. This quirky and compelling performance reminded everyone that “openness” need not only be a metaphor.