So many horrific images this week, but this one hits it for me. Where can you go?

So many horrific images this week, but this one hits it for me. Where can you go?

See also a full gallery of photos, with captions, via Andrew Sullivan’s blog.

So many horrific images this week, but this one hits it for me. Where can you go?

So many horrific images this week, but this one hits it for me. Where can you go?

See also a full gallery of photos, with captions, via Andrew Sullivan’s blog.

Just in case anyone needs more reasons to go to the Hungry Ocean conference in April, I’ll introduce our lineup of keynote speakers.

First up with be Margaret Cohen, who will talk on “The Imaginary Geography of the Sea.” Professor Cohen’s great new book, The Novel and the Sea, which I blogged about a little while ago, has just been published, and we’re all eager to hear her further thoughts on maritime craft, the international sea-novel, and other matters.

Later that day, Bernhard Klein will give a talk on early modern maritime studies, with the great title, “Fish Walking on Land.” Professor Klein has written widely on early modern maritime matters and has also edited two wonderful essays collections, Fictions of the Sea, and Sea-Changes: Historicizing the Ocean.

Rounding things out on Saturday evening will be Patsy Yeager, whose talk, “Oceanic Ecocriticism$” will expand upon some of her comments in the recent PMLA cluster she edited last spring. I’m wondering if her talk will also connect to her recent work on the “apotheosis of trash” and perils of tossing our waste into the world ocean.

Many things to look forward to.

Grim oceanic news out of the Pacific early this morning. 8.9 is a horrifying number, & the images out of Japan are on an absurd, inhuman scale, like something out of an old movie.  We called cousin Lucy in Hawaii at 3 am her time, and were relieved to hear they’d moved to higher ground. Deep rumblings crossing the deep Pacific today…

We called cousin Lucy in Hawaii at 3 am her time, and were relieved to hear they’d moved to higher ground. Deep rumblings crossing the deep Pacific today…

Everything, even horrible things, makes me think of books, and this morning it’s Kimberly Patton’s excellent The Sea Can Wash Away All Evils, a study of “Modern Marine Pollution and the Ancient Cathartic Ocean” (2007). She’s a professor at the Harvard Divinity School, & she’s looking here at a tradition of an all-cleansing ocean she locates in Euripides, in Inuit mythology, and in ancient Hindu texts. She also works closely with responses to the 2004 tsunami that hit Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

It’s a smart, resonant book that explores ancient ideas of pollution and cleansing and argues that they have real policy implications in the present, in our global unwillingness to come to terms with marine pollution and its consequences. Her suggestion that “environmental science — and environmental advocay — ignores the history of religion at a case” (xii) certainly convinces me. She also has interesting things to say about the Greek distinction between the salt sea, Pontus, on which Odysseus struggles, and the encircling fresh-water Okeanos, which is “full of eschatological peril” (63).

It’s a smart, resonant book that explores ancient ideas of pollution and cleansing and argues that they have real policy implications in the present, in our global unwillingness to come to terms with marine pollution and its consequences. Her suggestion that “environmental science — and environmental advocay — ignores the history of religion at a case” (xii) certainly convinces me. She also has interesting things to say about the Greek distinction between the salt sea, Pontus, on which Odysseus struggles, and the encircling fresh-water Okeanos, which is “full of eschatological peril” (63).

“The sea demands a reckoning” (123) she writes while exploring ancient Hindu texts. A grim lesson on a day like today. Sometimes it’s hard to separate moral and practical responses to our oceanic world.

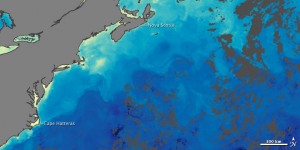

We all know the water’s cold in New England, but here’s a nice pair of images that shows why that matters. Here’s the pattern of chlorophyll concentrations off the east coat last August

And here’s the corresponding ocean temperatures at the same time, the end of last summer. The question is, will warming change this pattern, which has produced an upswell of nutrients and some of the richest fishing grounds on the planet? This area, from the Mid-Atlantic Bight to Georges Bank, is also a major carbon sink, so even if the fish aren’t as plentiful as they once were, there’s a lot to like about this stretch of ocean.

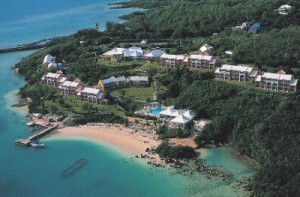

I registered this morning for Round the Sound, a 10km open water swim in Harrington Bay, Bermuda, on October 16, 2011.  We’ll stay here, at the Grotto Bay Resort. Should be a nice trip.

We’ll stay here, at the Grotto Bay Resort. Should be a nice trip.

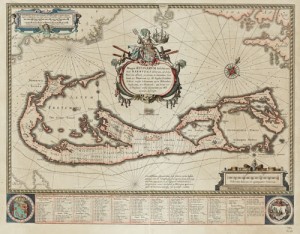

The wreck of the Sea-Venture is mostly in a museum on the island now, but 2011 does mark the 400th anniversary of a certain play that seems to draw upon accounts of that Atlantic hurricane of July 1609. The disaster ended up, in a convoluted way, to the rescuing of Jamestown, a permanent British settlement on Bermuda, and this map.

I suppose I should promise not to give long lectures about Shakespeare and oceanic culture to my fellow swimmers. Besides, it might make them swim faster…

For anyone’s who’s not see it yet, you should visit the website of Coriolis, an e-journal in Maritime Studies published by Mystic Seaport. The most recent issue features a great article by Colin Dewey on the ocean in English poetry from Dryden to Coleridge, an article on Melville’s poem “The Coming Storm,” and a nice intro by literary studies editor Dan Brayton.

If you’d like to contribute material, here’s the description:

Coriolis: Interdisciplinary Journal of Maritime Studies

A refereed forum on works of human interaction with the sea.Named for the prevailing global force that shapes human maritime experience, Coriolis offers scholars and serious researchers a refereed forum in which to disseminate work on human interaction with the seas. We define “maritime” broadly to include direct and indirect influences on human relationships through the fields of history, literature, art, nautical archaeology, material culture, and environmental studies. Coriolis is open to discussion of maritime connections through all periods and human cultures, and it includes freshwater as well as saltwater marine environments. We encourage works that explore interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches. The journal is international in scope and purpose, and we particularly welcome English-language scholarship from outside Europe and North America.

The principal contact is Paul O’Pecko <paul.opecko@mysticseaport.org> of the Blunt Library at Mystic, or you can contact anyone on the Editorial Team.

Future special issues on literature and the sea or other topics will follow!

Here’s another reason you want to go to the Hungry Ocean conference this spring…

Geoff Kaufman will be playing the JCB Library on Saturday afternoon —

Here’s the official flyer for the Hungry Ocean conference at the JCB Library in April. For more information, see my Hungry Ocean page.

The new home of Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Sciences (FES) is Kroon Hall, which is also the greenest and one of the best-looking academic buildings I’ve ever seen. I was there yesterday to give a guest seminar to the FES grad students, a wonderfully eclectic and smart bunch working on projects from an anthropological study of the ocean near Okinawa to evaluating a carbon farming project in Kenya to environmental art and ideas about geoengineering. I’m not sure how much Shakespeare they usually get in those green & glassy halls, but it was a great seminar.

The new home of Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Sciences (FES) is Kroon Hall, which is also the greenest and one of the best-looking academic buildings I’ve ever seen. I was there yesterday to give a guest seminar to the FES grad students, a wonderfully eclectic and smart bunch working on projects from an anthropological study of the ocean near Okinawa to evaluating a carbon farming project in Kenya to environmental art and ideas about geoengineering. I’m not sure how much Shakespeare they usually get in those green & glassy halls, but it was a great seminar.

I was invited by Professor Michael Dove,  an anthropologist and social ecologist. I remember coming to his old office when he brought me in the first time in 2008, and seeing the walls covered with ikat hangings and woven baskets from the Dayak people of Borneo, where he’d done field work. I was transported back to my vagabond days in 1990, when, after graduating from college and spending the summer working for the Exxon Valdez cleanup, I spent six or eight months redistributing Exxon’s cash among the Indonesian islands, including Java, Bali, Sumatra, Sumba, Sulawesi, and Borneo. I even hiked up Mt Merapi in Java, the volcano about which Professor Dove has written in the context of cultural responses to natural disasters. I don’t know if that’s why he gave me such a nice introduction, praising my writing and suggesting that my work helps him rethink how we talk about ecological disorder.

an anthropologist and social ecologist. I remember coming to his old office when he brought me in the first time in 2008, and seeing the walls covered with ikat hangings and woven baskets from the Dayak people of Borneo, where he’d done field work. I was transported back to my vagabond days in 1990, when, after graduating from college and spending the summer working for the Exxon Valdez cleanup, I spent six or eight months redistributing Exxon’s cash among the Indonesian islands, including Java, Bali, Sumatra, Sumba, Sulawesi, and Borneo. I even hiked up Mt Merapi in Java, the volcano about which Professor Dove has written in the context of cultural responses to natural disasters. I don’t know if that’s why he gave me such a nice introduction, praising my writing and suggesting that my work helps him rethink how we talk about ecological disorder.

For the seminar, the students had read a sample of my ecocritical articles, some chapters from Shakespeare’s Ocean, and related material from Rob Watson & Bruno Latour. I always am curious about how worldly and non-literary types, including scientists and the policy/managerial scholars at FES, will react to my efforts to make literary analysis matter in ecological terms. There were some skeptical impulses — why such old plays? why not today’s literature? why only English? why not activisim? — and there were some disciplinary fault lines, as when an anthropology student wondered that I could build an argument from a single text, rather than a multitude of response data. But during the seminar, we were all right there together, wanting the same thing — a flexible and powerful language through which to bring together scientists, humanists, and policy makers to address ecological questions. My focus on the post-equilibrium shift is old hat to them, but my claim that early modern ideas about the plasticity of genre can help us generate better narratives about a changing environment is not. We kept coming back to the challenges of representing stasis and change, and human desires for both.

Some of the best questions I got had to do with what literary ecocriticism might say to an audience of environmental policy managers. Michael Dove suggested that literary understandings might help policy stewards de-naturalize their accepted narratives of natural order, which seems right to me, though it puts literary culture in the critique/cautionary position rather than intervening more directly. Is there a more direct story that literary culture can tell about our unstable environment, without falling into old sentimental traps? Are there stories that can emerge from focusing attention on the ocean’s shaping role in our environment — stories about sailors and swimmers, not warriors and kings, as I say in the book — that speak to the needs of FES students, forest managers, and policy makers? Good questions.

They call these “cloud streets.” They formed after the big winter storm on Jan 24. From Nasa’s Earth Observatory —

They call these “cloud streets.” They formed after the big winter storm on Jan 24. From Nasa’s Earth Observatory —

Cloud streets form when cold air blows over warmer waters, while a warmer air layer—or temperature inversion—rests over top of both. The comparatively warm water of the ocean gives up heat and moisture to the cold air mass above, and columns of heated air—thermals—naturally rise through the atmosphere. As they hit the temperature inversion like a lid, the air rolls over like the circulation in a pot of boiling water. The water in the warm air cools and condenses into flat-bottomed, fluffy-topped cumulus clouds that line up parallel to the wind.