At a certain point in the evening last Thursday I found myself standing on West 19th Street speaking with Bruno Latour. I assured him that I loved his play. It was, I said, “perfectly intelligible.” (What a strange thing to say!) I told him that I especially enjoyed its “exploratory flash.” (?) My words seemed to make him happy. I know I was happy!

I went to “Gaia Global Circus” at The Kitchen, where a crowd of (I suspect) mostly academics — my post-play beer party was two professors and five grad students — marked the U.N. Climate Summit with a play.

The star of the show was the set: a large rectangular canopy filled the stage, on which were tied 50-60 large helium balloons, so that the whole apparatus floated. It could be raised, lowered, held at an angle. The balloons exerted enough lift that the structure would slowly ascend if left untouched, but for most of the action at least some of the corners were tethered to the floor or held by actors. The four actors, who assumed multiple roles in the performance, told us at the start that the canopy was vulnerable to changes in the local temperature, to gusts of wind, and to being pushed and pulled around by the people on stage. At the play’s end the actors walked into the audience holding the canopy by four ropes attached to the corners and held it over us, so that we filled it with our applause.

The canopy was the most powerful and resonant symbolic representation of “climate” I’ve seen: awkwardly large and ungainly, subject to human manipulation but not quite controllable, beautiful and unstable. In the Q&A after, Latour mentioned twice (I think) that he feels the biggest change in the age of global warming is coming to understand climate as an instability, not a constant. The big, beautiful stage-machine canopy represented slow change and instability.

(To my mind, btw, I think Latour’s phrasing, like Bill McKibben’s, exaggerates the felt stability of the pre-Anthropocene climate — but I’m not going to indulge my own ocean-fueled enviro-theories in this post!)

I was lucky to have gone to Gaia Global Circus with Henry Turner, not just because of his always excellent company at the show & during pre- and post- conversations, but also because he knows one of the directors, Frederique Ait-Touati, who was part of the team adapting Latour’s work for performance. (An early version of the play that I found on Latour’s website and read before the show is only tangentially related to what we saw on Thursday night. But it’s fun, if you want to look at it: KOSMOKOLOS-TRANSLATION-GB.)

Frederique, a theater director, performer, and academic who’s written a great-looking book on early modern science fiction, spoke about transforming philosophy into theater. Latour commented on that in the Q&A also, in what I took to be his own celebration of the transformation of his work. “It’s not an argument,” he said, “but a dance.”

The show consisted of vignettes, passed among the four actors (two men and two women) in almost stand-up style. (Frederique told us that all four actors were trained in commedia del’arte, which made perfect sense.) They performed a series of roles, including Gaia herself under several guises, one of which was a somewhat naive American scientist named Virginia.

Alongside Gaia ranged a series of figures for human knowledge, including Sherlock Hood the “goody” scientist and TED, the “baddie” corporate apologist. Prophets of doom sang out: Cassandra from the Trojan War and the prophet Philippulus from Tintin. Frank Wolff, named after the bad-but-ultimately-redeemed astronaut from Tintin, presented the story of being born to a Russian cosmonaut in orbit, with a star’s-eye view of our blue planet. Noah put on a good show as he sought funding for the Ark. King Midas showed capitalism at work.

A couple of scenes stuck with me. Around the middle of the show, the actor who played TED took a turn as a UN leader — President Obama? Secretary Ban Ki-moon? — who, obviously exhausted, reported that at last the politicians had come to a resolution to which all parties would bind themselves. “We hereby resolve,” he said, clearly relieved to have something direct to report, “to sully the earth, and leave the cleaning up to our children.”

Not all the great lines were so grim. Toward the end of the ark plot, someone — not Noah, I don’t think, but I’m not sure who — imagined trying to build “an ark for staying, not going.” This vessel would be, another replied, the earth.

Other great elements weren’t verbal at all. In one scene two lovers met at a pier. They were ambushed by hundreds of plastic water bottles dumped on top of them, but they respond eventually by repurposing the bottles into art.

The last lines that I heard posed a question about the final celebration, in which the canopy covered the audience. “You don’t know,” someone said, “if you will marry the bride, or the cake, or the knife?”

The quick-paced and enigmatic movement from scene to scene didn’t lend itself to easy allegory. Some things seemed clear enough: we need more Sherlock Hoods, fewer TEDs, sympathy for Virginia/Gaia, and to listen to Cassandra/Philippulus. I loved the speed, urgency, and sheer beauty of the production, played out beneath 50-odd helium balloons pulling the canopy upward. The project wasn’t didactic but artistic, not an argument but a dance. Just keeping pace with it was enough.

Latour addressed the question of meaning obliquely in the Q&A. The object of the play, he said, wasn’t to figure out what to do about global warming. The object instead was to help us “to be up to the task.”

I’ve been mulling that phrase since Thursday night. What does it mean to be up to the task of global climate disruptions and an unstable environment? That we learn to match a disorderly world with complex art? That we don’t assume tomorrow will be like yesterday?

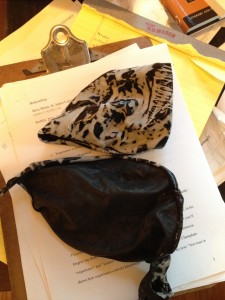

The play’s two-night New York run ended on Thursday, and they gave away the balloons to members of the audience. Mine was black, about four feet around, with a noticeable upward tug as I walked out of The Kitchen with it in my hand. I wanted to bring it home to my children, but I’m sorry to report that I left it overnight in the car. It burst with the temperature change.

[…] Positively. HERE. […]