I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of The Winter’s Tale at Tfana.

I’m in the middle of a three-plays-in-five-days theaterathon — Lear at BAM tomorrow! — so just some quick notes on a lively and ultimately very moving production of The Winter’s Tale at Tfana.

It’s a real treat to see this play now. I’m getting ready to travel to Mississippi next week, to give the James Edwin Savage Lecture on “Nature Loves to Err: Catastrophe and Ecology in The Winter’s Tale.” Not only my slides will be colored by Arin Arbus’s production at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn!

1. Dancing Bear / Thief in Snow

Arnie Burton in a bear suit

The bear is always the star of the show, and Arnie Burton’s turn in the bear suit was pure joy. Whether playing in the snow before the opening scene or performing an extended dance-off with Antigonus before the chase, his bear was playful, not destructive. This goofy generosity even amid destruction spilled over into the rest of the production, including during Burton’s expert audience-wrangling as Autolycus. Burton played both bear and thief with charisma and verve. Perhaps he was less threatening in each part that he could have been — but that was the spirit of the show, which emphasized wonder over horror. That’s probably why the Bohemian pastoral redemption of second half seemed more compelling that the Sicilian tragedy before intermission — but this somewhat ungainly and gorgeously excessive play is also built in that asymmetrical way.

2. How tall is heroism?

Dion Mucciacito as Polixenes; Kelley Curran as Hermione; Anatol Yusef as Leontes

I’m 6’4″ tall, and I basically see the world as being full of people mostly the same as my very normal height, with a few others who are a couple of inches shorter. But I spent a lot of time thinking about height during the first half of this show, partly because Kelley Curran’s authoritative Hermione towered over Anatol Yusef’s Leontes. The opening scene, in which the Queen convinces the royal guest to stay after he has refused at the King’s request, performed competing male and female forms of authority. “A lady’s verily,” Hermione quipped, “is as potent as a lord’s.” The height differential staged that rivalry in interestingly visual ways that other characters took up also: Polixenes was just a bit taller than Hermione, but in Bohemia both Clown and Shepherd were towering string beans. During the trial scene, King Leontes mounted a throne that put his head just above his now-disgraced Queen, but he descended in response to her powerfully-delivered self-defense. Am I superficial if I thought Yusef’s Leontes, like his Laertes last summer at the Public, a bit underpowered? Maybe I am. I thought Yusef’s line readings were overly smooth and somewhat disengaged, even during the rising eruptions of his jealousy (1.2). He was clear, which is a good thing, but he was not, to my ears, authoritative. This play distinguishes itself by its trio of powerful women, Hermione, Paulina, and Perdita, standing up against the male monarchs, but I thought this Leontes wasn’t really holding his end up as well as he might.

3. Hermione and the shapes of female power

A more positive way to frame that quibble would be to note that Curran’s Hermione stole the show whenever she was onstage, including a stunning statue scene that brought her back in a quasi-wedding gown. Mahira Kakkar’s Paulina was also a powerful stage presence, perhaps even a bit bullying toward Leontes after he’s broken his kingdom and family. Nicole Rodenberg’s Perdita rounded out the female trio. All three gave great performances, but of the male actors only Eddie Ray Jackson’s Florizel, and perhaps also Burton’s Autolycus, seemed able to match them.

John Keating and Ed Malone as wet clowns

Hermione’s pregnant body in the opening scene carried a powerful stage charge, and a moment in which she invited Polixenes to touch her belly and feel the hidden baby move was staged as a key trigger for Leontes’s regicidal rage. In a strange extension of the play’s performance of pregnancy, the country maids Mopsa and Dorcas (Maechi Aharanwa and Liz Wisan) of 4.4 were both also played as heavily pregnant. During their joint performance of the “Two Maids Wooing a Man” ballad, they even belly-butted each other, sumo style. The audience appreciated the excess of the show Autolycus staged, but it seemed symbolically confusing.

4. Time, the Oracle, the Statue

At the moment I’m thinking obsessively about “Time, the Chorus” in relation to my upcoming talk at Ole Miss and also regarding my general #pluralizetheAnthropocene ideas. In Brooklyn right now, the bear gets top billing. Robert Langdon Lloyd played a creditable white-bearded Old Man Time, but the more striking theatrical coup was the Oracle. Arbus’s direction emphasized the formal theatricality of the Oracle; Michael Rogers, who also played an impressive Camillo, sat stoic on the side of the stage as Hermione orated and Leontes dismissed her — but it was clear that Apollo would have the final word. Like the statue in the final scene, the Oracle was set apart from the action. The non-Oracular clarity of the God’s words knocked the king to his knees: “Hermione is chaste, Polixenes, blameless, Camillo a true subject, Leontes a jealous tyrant…” Yusef’s finest moment as Leontes, to my mind, came in response to the Oracle: he doubled up, fell, and clapped his hands to his mouth, unable to speak. His wretched reposte, “There is no truth at all i’th’ oracle,” seemed hauled out from deep in his jealous bowels. He could not look at his Queen as he clung to her supposed guilt.

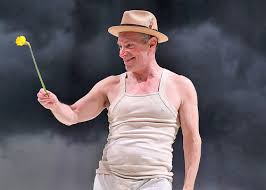

Arnie Burton as Autolycus looking for clothes to steal

5. Clowns and other responses to the storm

The other element of the play that I’ll be talking about next week is (of course) the shipwreck scene, which also doubles as the bear scene and the transition from tragic Sicilia to tragicomic Bohemia. The bear stole the show, but the Clown who buried half-eaten Antigonus, played by Ed Malone, and the Old Shepherd who found the infant castaway, played by John Keating, performed the shift into comic verve. Costume changes carried us into the new Bohemian mode: the rural men wore yellow slickers for the storm scene, and Autolycus sang his first song in just his skivvies. By contrast with the evening-wear formality of the Sicilian court, we clearly had arrived at a more practical place.

6. Mamillius

Memories of the dead son linger after the statue comes back to life. In this production, Eli Rayman as Mamillius took a silent turn before the final curtain, running in between Hermione and Leontes after the final non-rhyming lines had been pronounced. The symbolism was pretty on the nose — the dead boy flashed in between the couple’s efforts to reunify their marriage — but the royal pair still walked off together. I’ve only seen the full impact of the child’s death played once — in a devastating final tableau by Propeller at BAM in 2005 — but I appreciated the hint here.

Hermione, Leontes, and Nicole Rodenburg as Perdita, after that which was lost is found

Get to Fort Greene by April 15 to see this one!