I’ve been looking for the last piece of the theoretical puzzle for the shipwreck book, and I think this big book on “anthropotechnics” might help me out. Peter Sloterdijk’s not writing about catastrophe, nor about the early modern ocean, but his focus on practice and vertical distinctions, on “the distinction between the practising and the untrained” (3) strikes a chord. “It is time,” Sloterdijk writes, “to reveal humans as the beings who result from repetition” (4). “[T]he future should present itself under the sign of the exercise” (4). He’s not writing about seamanship or the shaping force of maritime labor exactly, but…

I’ve been looking for the last piece of the theoretical puzzle for the shipwreck book, and I think this big book on “anthropotechnics” might help me out. Peter Sloterdijk’s not writing about catastrophe, nor about the early modern ocean, but his focus on practice and vertical distinctions, on “the distinction between the practising and the untrained” (3) strikes a chord. “It is time,” Sloterdijk writes, “to reveal humans as the beings who result from repetition” (4). “[T]he future should present itself under the sign of the exercise” (4). He’s not writing about seamanship or the shaping force of maritime labor exactly, but…

By anthropo-technics, Sloterdijk means a labor of self-shaping, of cultivating a repeated practice or set of habits as a way to transform or transfigure the human condition. It’s a “de-spiritualisation of asceticism” (61), a form of “acrobatics” (125) or a reworking of “philosophy as athletics” (194-96). Self-shaping labors create a bridge between natural limits and cultural forms: “In truth, the crossing from nature to culture and vice versa has always stood wide open. It leads across an easily accessible bridge, the practising life” (11).

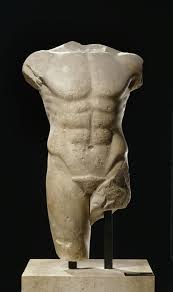

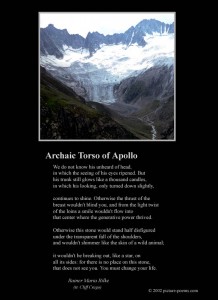

The models for these techniques come from ancient monastic and athletic orders, but the rebirth Sloterdijk uncovers comes through a series of late 19c figures: Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” from which he gets his title; Nietzsche’s Ubermensch as bridge or transition; Foucault’s “care of the self”; Kafka’s “Hunger Artist“; even the revitalization of the Olympics in 1896. At times this somewhat rambling book, which touches on a massive variety of references, from Hercules at the cross-roads (“the primal ethical scene of Europe” 417) to post-Communist eastern Europe, implies that this human-shaping process is distinctly modern, or at least that its forms are changing as we enter the 21c. For Sloterdijk, Nietzsche alone in the later 19c “unconditionally embraced the primacy of the vertical” (177), and it is that vertical impulse, the desire for self-mastery, and the consequent “de-passivizing” (195) of human existence, that this book celebrates.

I don’t buy the now-you-see-it historicist novelty, but the value Sloterdijk’s analysis accords to incremental efforts of skill and practice that gradually, perhaps invisibly, shape the way the body engages its nonhuman environment, seems important. I think of the ocean-going sailor, that favorite literary symbol from Odysseus to Ishmael, and the way these figures use technology-driven alliances, networks, human and nonhuman creatures and objects working in concert and in tension to survive in unfriendly waters. The mariner’s metis is an anthropotechnic practice, though perhaps it owes more to its surrounding environment than, say, the acrobat’s balance.

Reading seamanship in moments of crisis as an anthropotechnics, an attempt to follow the unrefusable command the fractured torso of Apollo gives Rilke — you must change your life – suggests that shipwrecked sailors shape themselves in two senses: they become vessels of survival, body-sized rafts in turbulent waters, and they also become vessels of meaning, symbolic buoys in violent seas. Think of Ishmael, on the “margin” of the Pequod’s wreck, “slowly drawn towards the closing vortex” but entangling himself with that last vertically-moving object, the “coffin life-buoy” that “shot lengthwise from the sea” to preserve him. His odyssey of practice matches a slow accumulation of skills and knowledge alongside his doomed captain’s quest. To survive alone, to escape to tell the tale, is a form of life-changing.

It’s a tribute to the spell of any major theoretical work that while you’re reading it, it seems universally applicable. I’ve been seeing anthropotechnics everywhere, from my local YMCA pool to the crowded lanes of I-95. Isn’t this what literature and philosophy is for: to teach us how to live?

Sloterdijk’s massive book ends with a plea that a practiced life respond to “the global crisis” (444) through the “return of the sublime” (446). He asks that we invoke not the lost Golden Age of perfect abundance but instead imagine a new Silver Age, one step down the ladder but still above Iron and Lead. “Critique,” he notes, sounding somewhat like Latour (who he cites just once), “is replaced by an affirmative theory of civilization, supported by a General Immunology” (425). As a way of responding to the ecological and human disasters Sloterdijk links to globalization (447-48), General Immunology has an utopian flavor, including a pun on the ethical heart of the Marxist left, “co-immunism” (452), which he connects to a “horizon of co-operative ascetisims” (452).

I’m not clear exactly how he moves from individual anthropotechnic practices to these massive co-operative forms. But it’s fun to imagine it!

I’m not clear exactly how he moves from individual anthropotechnic practices to these massive co-operative forms. But it’s fun to imagine it!

Leave a Reply