One of our four paper-groups for “Watery Thinking” will explore the perils and possibilities of staging immersion. Lyn Tribble’s essay provides a helpful overview of the “dramaturgy of immersion”:

In Shipwreck Modernity, Steve Mentz writes that “wet representations emphasize the shock of immersion and its threat to human understanding and survival.” On the early modern stage, the dramaturgy of immersion is complex because it cannot usually be directly staged. Thomas Heywood, naturally, is one of the few exceptions to this general rule; in The Brazen Age, he stages Hercules fording a river to save a nymph from the centaur Nessus. More often, immersion is either narrated by a character or a chorus or is represented through an off-stage on-stage transaction, an exchange between spaces, or as Lowell Duckert has noted, ‘a before and after’ (5). Many wet plays draw from the romance tradition, marked by a narrated or implied offstage shipwreck and subsequent rescue or rescues. Heywood’s The Four Prentices of London presents no less than four such moments in the aftermath of a shipwreck of the brothers: their boats “split on strange rockes, and they enforc’t to swim to / Save their desperate lives.” The brothers are each rescued at “seueral corners of the world.” Godfrey enters “as newly landed and half naked” in Bologne and helps to deliver the city from the Spaniards. Guy attracts the attention of the King of France and his daughter, who watch him come ashore on a raft and realize that although he is “basely clad” he has “sparks of honor in his eye.” The stage direction reads “Enter the King of France, and his daughter walking: to them Guy all wet. The Lady entreateth her father for his entertainement: which is granted; and rich cloathes are put about him: & so Exeunt.Charles enters “all wet with his sword” and becomes the captain of a group of Italian banditti, while Eustace fetches up on the shore of Ireland. Eastward Hoe parodies such a scene, when Slitgut narrates from ‘above’ the fortunes of a set of drunken characters who struggle to shore off the Thames after their boats are capsized. The dynamic of a ‘wet’ character rescued on land and afforded with clothing is also featured in Pericles, in which the titular character enters wet and is furnished with a cloak by passing fishermen (who shortly fish up his armour in a net). So the romance dynamic of staged wetness involves the entry of a victim, ‘naked,’ half-naked or ‘basely clad,’ and a rescue that takes the character out of the watery margins and affords him with dry clothes or a cloak that reintegrates him into the dry world of the stage.

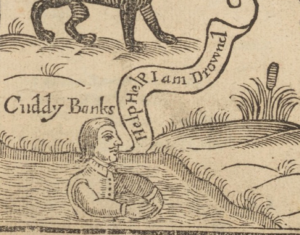

But immersion is not only a feature of the romance tradition; some characters are submerged in the everyday wetscapes of early modern England. Dunking is inherent comic and inherently humiliating. If being shipwrecked in the ocean in romantic, falling into a ditch or a pond or a lake — or ditch running by the Thames near Windsor — is a form of comic retribution. Such a fate befalls Cuddy in The Witch of Edmonton, who is lured by an evil spirit into a dark watery landscape and nearly drowns, as the title page of the play shows:

Cuddy’s misadventure is a reminder of the grim statistics around drowning in early modern England. Drowning was one of the chief hazards of everyday life, accounting for up to half of all accidental deaths. Some drowned at sea or while pursuing occupations on the river, but many more died in more quotidian landscapes. Water was everywhere: water pits for household use, ditches, streams, standing water from rain, rivers. In Accidents and Violent Death in Early Modern London, Craig Spence argues that despite the prevalence of drowning, “little attention was paid to those who suffered such a fate on an individual basis . . . .Perhaps a more difficult issue for early modern mentalities, and one that may go some way to explain this omission of cultural recognition, was the character of drowning as at once irreversible but also unavoidable.”

Conversation around this group of papers will help us explore what Tribble describes as the “physiology of immersion” and the “nexus of imagination, physiology, skill and affect” in the waterscapes of early modern England.

For more fun with watery dramaturgy, here’s a great blog post about back-stage possibilities for the opening scene of The Tempest, from Hester Lees-Jeffries.