Our deadline is today, and the trickle of papers for the #shax2020 seminar that Nic Helms and I are leading this spring in Denver started a few days ago. Our idea in “Watery Thinking” is to ask our esteemed seminar members to bring together two of our favorite things, the ecopoetics of water and the structures of human cognition. We’re both interested in both of these things, even though I come to the seminar flying my blue flag and Nic has recently published an excellent book on Shakespeare and cognitive theory, Cognition, Mindreading, and Shakespeare’s Characters.

Over the next few months, as an extended pre-game rollout before the seminar in April, Nic and I and some of our seminar members will be blogging about these topics, including new discoveries and ideas we find as we wade into the seminar’s collective work.

As we wait to read the contributions of the seminar members, I thought I’d offer a few quick ideas, drawn partly from my own work but even more from thoughts sparked by reading abstracts and the bibliographies the group has been sharing.

- Mindreading: Nic’s book uses theories of cognition to explore what he calls “mindreading” as a way to reconsider the Shakespearean figures. Of particular interest in a watery context is his reading of the Jailor’s Daughter’s incoherent speech in Two Noble Kinsmen, which includes a vision of maritime crisis. When she displays her madness through the metaphor of a ship at sea — “Out with the mainsail! — Where’s your whistle, masters?” (4.1.148) — she presents herself through a form of symbolic disorder that Nic powerfully links to Hamlet and Cordelia, among others. The explosive gap of “nothing” in the opening of King Lear may gesture toward the flooded landscapes of act 4 (that’s my watery reading of the play) but Nic’s focus on fractured cognition suggests that linguistic coherence flows both toward salty metaphors and into dramatic structures that represent thought.

- Theatrics of Water: I’m looking forward to reading lots of papers on stage practices. There was a time, it seems to me, when every modern stage featured a water hazard. I think I first remember this sort of thing in a stage version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses that I saw in New York around the late ’90s (?), and I remember a production of Much Ado in London in which the ingenious Benedick, played by Simon Russell Beale, jumped into the pool when he needed a place to hide. At a certain point it seemed a bit gimmicky, though the recently-revived splash-tastic Tempest by Synetic Theatre in DC was pure genius. But I wonder — might these 20-21c tricks have something to say to the staging of water in the early modern period? Water is a resistant, resilient element: it gets everywhere (as a young padawan famously said about a dryer substance), and can’t easily be contained. What’s the place of water’s movement within (or on top of?) the carefully controlled movements of a stage play? Does water represent the limits of acting, a nonhuman collaborator who, perhaps like the dog in Two Gents, always threatens to steal every scene?

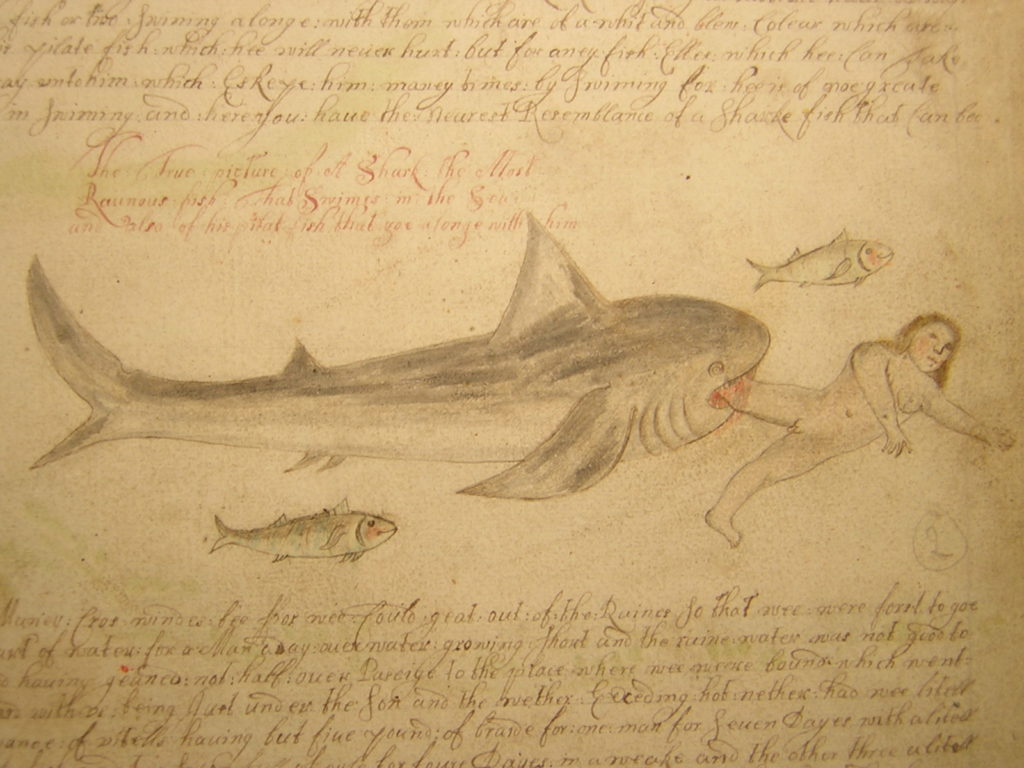

- Fluid Metaphors: “The sea is not a metaphor,” cries Hester Blum in PMLA in one of the most influential critical statements in the development of the blue humanities. Her salutary focus on the material reality of the ocean, from the mast-head to the polar regions, has greatly influenced my thinking about oceanic cultures and literatures. But I also wonder, especially in an early modern context in which many of our writers were, unlike Melville or Conrad, not themselves sailors, about reversing her rallying-cry. The sea is always partly a metaphor, as in Shakespeare’s “hungry ocean” (Sonnet 64) or Spenser’s about-to-be-erased strand (Amoretti 75). For me, the overlap between metaphor and materiality gets at the heart of things. How much real salt is in that sonnet? How much poetry in the salt-stained journal of that young midshipman? What are the formal features of an ocean wave?

- Thinking with Things: Though I worry that the pdf I shared with the seminar was hard to read, one of the most influential texts for the overlap between water and cognition that I’ve run across is Edwin Hutchins’s great 1995 book Cognition in the Wild, which treats the human and nonhuman assemblages working together in a U.S. Navy ship. Hutchins’s portrait of the ship responding to crisis emphasizes plural forms working on concert: “No single individual on the bridge acting alone — neither the captain nor the navigator nor the quartermaster chief supervising the navigation crews — could have kept control of the ship and brought it safely to anchor. Many kinds of thinking were required to perform this task” (5). The multiple humans and machines of the Navy ship may, in some ways, resemble the multiple humans and machines that make theaters work.

So many ideas! I can’t wait to see the seminar papers! More in a few weeks as we start to read and think about the papers.