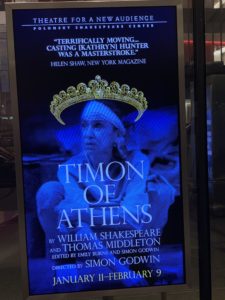

I went to see Timon of Athens in Brooklyn last night, as my phone chirped to me about the United Kingdom’s Brexit out of the European Union and the United States Senate’s willful refusal to perform its constitutional duty of hearing evidence about an out of control executive. Misanthropy and rage seemed like good ideas.

The play teems with anger, and I would have happily joined in bringing the wrath. Watching rich folks fiddle while the world burns feels pretty on point. The headline-quip from the Times review, that Simon Godwin’s production, currently in Brooklyn after a run in Stratford-upon-Avon, is “Shakespeare for the Occupy era” feels right. Elia Monte-Brown’s Alcibiades led her army against Athens bearing signs attacking the rich and support for the “dispossessed.” It’s necessary, I think, to re-imagine this play’s combination of generosity and despair as a comment for our own age, in which catastrophic income inequality makes our political collective unable to respond to so many challenges. Rewriting Alcibiades as revolutionary required added some lines, and cutting some scenes, but overall I liked the Occupy-thread of this somewhat disjointed play. I’d like to see Monte-Brown play Henry V next!

Going into the play, I worried that the city scenes might be a bit dull. Many of them probably written by (the brilliant) Thomas Middleton, who collaborated with Shakespeare on the play. They are more spectacle than story, driven less by emotional connection than by Middleton’s customary satiric bite. To my surprise, I loved the scenes that featured the full ensemble of actors, variously cast as artists, senators, dinner guests, soldiers in Alcibiades’s army, and, memorably near the close, a trio of thieves ultimately converted away from the bad life by Timon’s saintly example. TImon fixed them through a gorgeous rendition of one of my favorite speeches in Shakespeare:

I’ll example you with thievery:

The sun’s a thief, and with his great attraction

Robs the vast sea; the moon’s an arrant thief

And her pale fire she snatches from the sun;

The sea’s a thief whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears; the earth’s a thief

That feeds and breeds by a composture stol’n

From general excrement. Each thing’s a thief. (4.3.430-37)

I’ve wrestled with those lines as a vision of destructive ecological connection, but last night I heard them more intensely in narrative context, as the disillusioned Timon’s way to discourage petty theft. It was a good reminder of how such quotable poetry, which Nabokov used to create his novel Pale Fire, also has a purely local resonance.

The cast also performed gorgeously during the early scenes of Timon’s opulence, including lively accompaniment by a three-piece band, and two musical renditions of Sonnet 53, performed in English in the first banquet and later in an abbreviated Greek version. The feeling of social play and cohesion, especially between the scam-artists Poet and Painter, who just want to get money from Timon, were strangely appealing. Even when they followed Timon into the woods in the second half, having heard a (true) rumor that he’d discovered more gold, they seemed excessive rather than rapacious. It was hard to hate them, even though they were parasites.

The play’s core remains rage, but not at these hangers-on so much as the treacherous aristocrats, in particular at the Senators who won’t loan Timon money, but more comprehensively at the human condition writ large. Kathryn Hunter gave a physically dazzling performance as Lady Timon, dancing on the table in the first scene, splashing bowls of blood in the middle, and heaving great shovels of dirt onto the stage toward the close. She’s a powerfully generous actor, intent on connecting with other players on stage, as well as engaging the audience. At one point she handed me a pine cone and suggested that I feast with her in the woods. I was tempted to try a bite.

Did she reach the incandescent heights of Lear in the storm? At times I thought she played so generously that she couldn’t quite get all the way to full misanthropy. Last spring I saw Glenda Jackson, another diminutive woman, play Lear on Broadway. I’m not sure if Hunter quite matched her. Hunter’s Timon was more emotionally open than Jackson’s Lear — but perhaps in these regal rage-beasts we in the audience need to feel that something isn’t available to us, that we need to clutch and peer into a human darkness that isn’t entirely open to be seen.

Timon’s closest confidant in the play is the cynic Apemantus, played by Arnie Burton with a bounce in his step that echoed his turn as Autolycus in Tfana’s Winter’s Tale in 2018. When Apemantus got into a dirt-smearing fight with reclusive Timon in the woods, the production follows the play’s insult-comedy patter — “Beast!” cries Apemantus; “Slave!” retorts Timon; “Toad!” “Rogue, rogue, rogue!” (4.3.369-70) — but the sentimental embrace between the two that ended this scene was the director’s idea, not Shakespeare’s or Middleton’s.

It’s hard to grudge solitary and doomed Timon a little affection. Though when I left the theater and walked out in damp drizzly Brooklyn in January, I could not help but feel that my intense disgust at this day of Brexit and impeachment hadn’t quite been matched by this production. Maybe that’s a tribute to the production’s efforts to humanize the angry old aristocrat?

Get to Brooklyn before Feb 9 if you can!