The part of my trip to France this past summer that I’ve still been meaning to write about happened underground. We went down into three famous caves: Pech Merle, Lascaux II, and the Gouffre de Padirac. Three very different sunless worlds.

One reason I’ve not gotten to writing these visits up is that Olivia, as part of the utterly brilliant travel journal she kept during our summer travels in Iceland and France, beat me to the pen (or keyboard). She’s agreed to let me quote from her descriptions here. Really I don’t have that much to add. She turns twelve tomorrow — 10/10/14 — and, doting Daddy though I may be, I’m amazed by her sentences.

I’ll take the caves in reverse order of our descents.

Cave #3: Lascaux II

We went into the replica, an artificial cave which was opened to the public in 1983. The famous cave drawings, often described as prehistoric equivalents of the Sistine Chapel, were overwhelmingly beautiful. Art historians estimate that there are over 2,000 figures in Lascaux, the majority of which have been painstakingly replicated in the replica cave. I’ll let Olivia describe what it feels like to look at them. I pick up in the middle of her journal’s entry on Lascaux, when she starts thinking about why the guide, who was deeply committed to a religious interpretation of the artworks, called it the cave of dreams:

That is why it was called the cave of dreams to me. I have talked of leaving the world of reality when I dream, and coming to rest on the shores of imagination where anything is possible. There in Lascaux, though I wasn’t sleeping, I left the world of reality.

In the world of dreams the bulls ran freely, and I rode on a stag’s back as it jumped for joy at having escaped the dungeons of truth to a place where anything is possible, and you can climb over the rainbow high into the ever-blue sky and when you climb down again there is a cauldron full of gold waiting for you. In that world frowns are hidden, and smiles permanent, and I ran wild with the animals of Lascaux for the afternoon.

Cave #2: Gouffre de Padirac

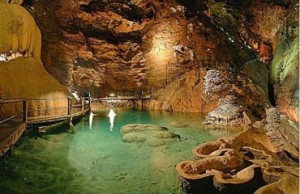

Our middle cave was artless. The Gouffre de Padirac is in the same region as many of the cave painting sites, but there are no surviving human traces in these wet caverns prior to the caves’ discovery in the late nineteenth century. It’s a massive limestone sink, with an underground river at the bottom which we crossed in gondolas on our way toward some amazing underground pools.

Olivia focused on the absence of humanity in that other-worldly space.

Do you ever get the feeling that you are in space floating among things that you don’t know, discovering things you didn’t know existed? That is what happened when I entered the Gouffre de Padirac.

Nothing else had ever trodden down these roads, breathed this air, and searched around with piercing eyes looking for secrets. I was brought back to the other cave with the paintings, clear marks of civilization before time. Here though, nothing touched this cave, no prehistoric creature had left its mark upon the wall, to be discovered, to be pondered over, to be admired. I was overwhelmed by the fact that the only living things in this cave were us. Nothing else, not fish, or insects, or other small creatures had ever breathed the fresh, cold air of the cave, nor seen the shining crystals within. I heard the whisper of the water moving quickly over

stones.

Cave #1: Pech Merle

The “other cave” was Pech Merle, a famous site of Neolithic paintings only about 20 minutes away from the lovely little village of St. Cirq-lapopie where we spent most of our two weeks in France. It was the first cave we visited, and one of the most intense art encounters I’ve had. Olivia called it the cave of lost time:

In the cave of lost time there is magic and power and forgotten wisdom waiting to be remembered. The cave dwellers left their marks upon the wall, and in the sparkling droplets of water secrets whisper, they laugh, they watch us as we pass, everything watches. They see us, but we cannot hope to see them, for man cannot penetrate that which is guarded in these caves.

I could picture the cave people making the curves and spots and circles with the black and red pigments mixing, perfecting, making a masterpiece that was to be remembered, and stared at for millennia after it was made. Did he know then that people ages after his time would look upon it? Was that his idea, or was it for pleasure? I wish I knew, wish I knew the answers that were buried in tombs when the ice covered all of Europe, never to be found, not yet at least, but never is a strong word, we can always hope.

The handprint and the wounded man were us, showing that even thousands of years ago we were there, fighting for our place in the world. Thousands of years ago we lived, and breathed, drank and ate, looked upon the world with the same two eyes we do now. What we thought then was a mystery, a mystery that was partly solved by the great paintings of old that stood before me, in all their glory. They were more royal than Buckingham Palace, stronger than all the armies in the world, more beautiful than all the dresses of queens, because they were man’s mark on the prehistoric world that was secret to them and animals and that is all. They swim before my eyes still, days later, and from them people thousands of years ago smile and wave at me, saying a last unforgettable goodbye.

When we settled on the Dordogne as our family destination within France, I was especially focused on seeing cave art. The kids grumbled sometimes when I gushed about my reading list: The Mind in the Cave, Juniper Fuse, some amazing picture books. When I read Olivia’s words in response to the three caves, I know I was right to have been excited.

Art hits the imagination with the mysteries of presence and persistence, things that are right there in front of you and have endured through time. There once was a human — perhaps not necessarily, despite Olivia’s phrasing, a “man” — who put his or her hand on that cave wall and blew red ochre pigment out of a tube onto it to create a lasting image. That artist is known and unknown to me, just like my writer-daughter who lives and grows in my home and turns twelve years old tomorrow.

Happy birthday, Olivia!

Leave a Reply