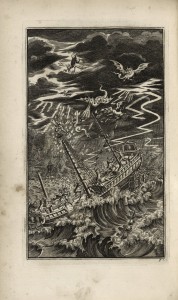

Here’s a cover image of The Tempest from a 1707 ed of Shakespeare’s Works that I used in the opening case of the Folger show last summer. If you look at the terror on the faces of the mariners, the demonic glee of Ariel in the clouds, & the bemused unconcern of Prospero on shore (hard to see on the left hand side), it’s a pretty good image of grad school in English.

Please comment below & read this image back for me: do you see a different allegory, of teaching or learning or something else?

(This’ll give me a chance to test the comments, & to approve each of you as a commentor for the blog going forward.)

Sadly, I have never read _The Tempest_ or even seen a performance of _The Tempest_. In truth, I always felt that Shakespeare was somewhat left out of my English education. In high school, we read Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, and Hamlet, but we didn’t do much with them. In college, I took Shakespeare on film, which was cool, but focused more on new representations than the original texts. The only real in-depth exposure I’ve had to Shakespeare was the course in the comedies that I took last fall, and let’s face it, the tragedies seem to be more heralded among Shakespeare scholars. So, to make my point, I am approaching this image as a blank slate. I can’t make any parallels between the image and the play. I can only make inferences from what I see.

As an allegory for graduate school, though, I think it’s a poor one, at least for my graduate experiences. There are probably schools where the faculty acts as distant by-standers, watching their students drown from the safety of the raised shore. At St. John’s and Montclair State, however, I have had nothing but positive experiences. At Montclair, my professors were always “on board” with me. They encouraged me to sail uncharted territory and helped navigate the open water. If the monsters were attacking, my professors showed me to the canons. Here at St. John’s, it seems that professors try to level with students, rather than placing themselves way above as “academic authorities.” Perhaps, I’m a bit biased, though, because I’ve been able to immediately establish a community as a member of the IWS.

I’m glad to see an early student comment to this post! My suggestion that the storm represents student experience was something of a joke, as I hope everyone realizes. That kind of self-conscious mockery is more common than perhaps one might think in the discourses of English. I do think that the post-storm scene (1.2) is very much an allegory of different kinds of pedagogical practice, as Prospero lectures to Miranda (who falls asleep), manipulates Ariel, and then berates Caliban. Certainly his position is always authoritative, and I think you’re right that in many ways the contemporary academic position has encouraged leveling and community building among students and faculty. We might talk about how much of that dovetails with new trends in media & network culture.

First, I have to say how much I love that I can open this image on my computer and use the zoom to look at it in such wonderful detail.

My initial thoughts on this image as an allegory for teaching and learning began with considering Prospero as the teacher, as he is throughout the play. He’s the one who moves all the pieces around the chess board, and certainly sees himself as an instructor. What is striking in this particular image is how very small he is. At first glance, you might not even seem him. He’s in the background directing this storm, but what a small figure he is. To carry the allegory through, then, the teacher may be a small figure in a student’s education but has an incredibly widespread effect on that student. Look at the size of this tempest (the education)! I think this presents an interesting quandary for the teacher. How involved should he/she try to be in the student’s education? Should he try to make himself as small as possible (realizing the great effect he has) and try to step back, letting the student succeed or fail as the case may be? Or should he, as Prospero does so much throughout the play, step in and instruct; set things in motion as he desires them to be?

Something else I cannot get out of my head is that this tempest is magic. It’s not real, not from nature. Yet it certainly feels real to the mariners. This thought seems to suggest that our education (the tempest) is really a constructed entity, which I think is right to a certain extent. Someone (whether the teacher, an institution, or the student, or a combination of these) is always constructing the tenets of our education. It certainly feels real while we are inside it, but once we leave the “bubble” of the education system, it is easier to see the constructs, or the magic that created the tempest.

A nice, imaginative post. I certainly agree that Prospero’s small size (the actual page size of the book isn’t much more than the cover of our Norton ed.) helps tweak the wizard-as-educator allegory. The question of when to step forward & when to step back is crucial to all classroom management, & also to Prospero’s role in the play: look esp at 1.2 for his careful “one on one conferencing” with each of his students. You might also rethink the Epilogue in these terms, as a kind of triumph for an educator (rather than a wistful farewell for the magus).

On your second point – so is education as unreal-and-real as the theater? Surely Shakespeare’s thinking about that, too?

I have had some time to digest this picture from the prior semester reading The Tempest, and I almost did my paper on this play, so I am glad I have another opportunity to play with some ideas. The last time I looked at this image, I was mostly focused on the sinking ship, and the passengers on board. I have never really given thought to Prospero’s presence in the corner – a very small figure dressed in what appears to be traditional renaissance garb and holding a wand in his hand. Whose show is it though? Prospero orders Ariel to carry out the tempest “to point” (13) yet Ariel took it upon himself to play some tricks of his own which left Prospero inquiring about his tactics and the final outcome. I am not suggesting a contest of power between Ariel and Prospero (or maybe it is – something I’ll have to think more about), but in the opening act, Ariel clearly performs his own version of Prospero’s order. Ariel is given a more prominent space in the image, but the wand states that Prospero is the true maestro. Again, I am not disputing this, it just seems strange as it appears that Prospero was “watching” instead of “wanding.” Further, Miranda is also present watching the wreck from the land. She confronts Prospero as to if and why he troubled the ship and its crew, who must have a royal subject (that statement in itself is interesting to me). Both witness the wreck from the shore. Why is Miranda not in the image weeping for the crew? Interesting…

Concerning the allegory – might not be to far off from the academic experience – a lot of wand waving happens and performance leaving lots of confusion and chaos yet somehow…someone (or entity) appears to have it under control.

Just a quick note about “wand-waving” — I think the reason I was thinking about this image as an allegory of academic experience is the play between chaos and order. That resonates, for me, with the classroom — which is always supposed to end up feeling orderly, with Prospero in the wings or at the center, but sometimes can be more vexed than that in practice. I sometimes talk about the “myth of the semester” — the idea that all a student’s questions and efforts can conveniently arrive at a terminal point after a certain fixed number of weeks in class — as something that’s both useful and obviously false. This scene strikes me as representing something like the myth of the seminar table — chaotic & even full of fire, but with a secret order hovering alongside.

Re: education as unreal-and-real as the theater. Yes, very interesting! As an actor, director, and audience member, it’s always a “problem” (though I hesitate to label it as such — because it’s also what I love about the theater) how fleeting a performance is. We are (or hope to be) completely in the moment. Of course, as soon as the curtain goes down, the play is gone. You can’t press rewind on it and watch it again. And the words on the page are so different that they don’t recapture the experience.

It’s part of what ADK Shakes (that’s my company) does with THE RAW project. So far we have done only one performance of each play — 1 Henry VI, 2 Henry VI, 3 Henry VI, and Richard III. It compounds this feeling of being in the moment for the actor. With a longer run, an actor gets to revisit the play, their character(s), and relationships, but with THE RAW, there’s only one chance — as there is for the audience too. We do this so the play can feel as “real” as possible, but of course it’s still completely constructed, “unreal.”

I think The Tempest is such a wonderful stage (pardon the pun) to think about this real/unreal “problem” in relation to theater and to education, among other things. I can’t wait to hear more about what everyone thinks these other things might be.

Yes, real and unreal is a very good way to sum up how on the one hand, the academic environment or a seminar table provides the sense of camaraderie where despite the various emotions that take place, the course ends with what seems to tidy up those ideas, but in many ways they remain behind and the myth moves forward if this makes sense…

Tara, have you read Cities of the Dead by Joseph Roach? It takes a look at circum-atlantic performance studies as a relationship between memory and history – particularly the process of surrogation in which actors/individuals seek to constantly reproduce the original. Your comments about being real and unreal – desire to “recapture the experience” – make me think of this as actors often try to reproduce an authentic performance in order to summon the purity of origins. His analysis on theatrical performances of Othello are pretty fascinating. If you are interested…I can bring it in for you to take a look.

Thanks, Regina! I would love to take a look at it, as I’m not familiar with it at all.

Joe Roach is someone for you to dig into, Tara. He’s one of the best current scholars of performance in theory & practice. Start with *Cities of the Dead*, but don’t stop there.

I read books since the age of 7 and honestly I have never payed too much attention to the covers of the books… However, this image is definitely worth a discussion.

I think that the true key to the understanding of this beautiful tragycomedy, which definitely is the wreath of all latest Shakespeare’s plays and in certain way the ending of his artistic journey, is the play’s musical interpretation. It is no coincidence that The Tempest is a lot more symphonic than all other Shakespeare’s plays; it appears to be a game of sounds, songs, happy and sad moans: roars of the waves, howling of the wind, moans of the tempest, whispers of the woods, rustles of the human steps – the voices of the nature, the voices of the universe…

While looking at the image, we don’t just see the tempest, we actually can hear it. The tempest is in the center of the play and Prospero is a conductor of this spectacular symphony. Look at him, so wise, so kind, how he rules the fates, he is restraining selfish motives in himself and in the others, he is conducting the lives, leading them to the everybody’s, universal good…

There’s a great, mid-20th century book called *The Shakespearean Tempest* by G. Wilson Knight that posits, in a slighlty manic fashion compete with a wheel-chart, etc., that the two dominant thematic principles in Shakespeare are music, as a representation of order, and storms, as images of disorder. Your post suggests that you’re responding along similar lines. I think also of Wallace Stevens’s “The Idea of Order in Key West” or again of Mandelshtam: “Whoever finds a horseshoe…”

I may be way off but the first thing I think of when I look at this image, with teaching in mind, is the student trying to navigate the world at large. The world is a chaotic and confusing place. Each student will handle life differently when they are on their own without the formal guidance of a parent or teacher. If you look at the mariners/students they are all in different positions. A couple are holding on for dear life, two others are trying to do something with the sail, others have fallen, and there is at least one mariner who looks like he has thrown his arms up in surrender. I think it’s pretty accurate for how people tend to deal with life. Futher, look at Prospero’s tiny but formidable image on the side. His stance is almost casual. He’s got one hand on his hip and the other hand is holding the wand up as though he is about to do something. His wand is not pointed at the creatures above or even at the mariners. It’s just up, as though he’s waiting for something. Perhaps he’s waiting for the mariner’s to pay attention to him so that he can help them. To me that speaks to what I have been learning about engaging the student. As teachers we can only guide or educate or “help” them if we can fully engage them. So how do we do that and be heard above the maelstrom of personal and worldly distractions?

That’s a nice way to respond to the variety and visual complexity in the image. I think you’re quite right to suggest that the educational relationship is full of different experiences — we might say, “full of noises, strange sounds that give delight and hurt not.” Except that sometimes, I think, learning can be somewhat uncomfortable, as in this image.

I agree. Deciding to puruse highter education at this stage of my life has been exciting and scary. It’s always an uncomfortable feeling when trying to assess what value you bring into a new environment. The “strange sounds” I have been encountering are the theoretical terms and ideas that I have never heard of before. Yet, the “delight” I am experiencing comes from the interest these terms are raising for me. I would guess that once all of these new terms start to gel, the waters will calm and I can look straight ahead and depend wholly on my own sense of direction rather than for a Prospero to rescue or guide me.

Metaphors are tricky things, but I’m not sure that calm waters & a perfectly clear sense of direction are what you’re likely to end up with. We can talk more about this on Tuesday, but my own sense is that the skills & habits of the discourse(s) of English are at least as much about managing disorder as maintaining order. I do think it’s important not to rely overmuch on smoke-and-mirrors (or blog & whiteboard) Prosperos.

If I could continue some of the dialectical thinking that I’m picking up on, the idea of the real vs. unreal is an interesting mode of thought in regards to graduate studies and teaching at any level. I tend to think of reality as being constructed, so I don’t think there is a large gap between the ideas of real vs. unreal. I do think that we need to step outside and see the real in the situation or vice versa, and an imaginative construct such as a play can help us to do that. In terms of the cover art, there is this mix of real and unreal, but it’s an interesting discussion to examine what is real. Although Prospero is using magic, the power he has in wielding it is very real. Certainly, our instructors in wielding their magic have a certain power in the direction of our studies and thoughts. And as Tara was saying, this magic is very real for the passengers of the ship undergoing the experience of this tempest. As students, there are many things beyond our control that are part of this constructed world, but are a very real experience. As a senior undergraduate and then at the Masters level, I found that studies can be very unreal, overly theoretical at times and I wonder how it relates to the “real” world. At the same time, I think a discussion of theory in relation the “real” world can be an enlightening experience.

The “such things as dreams are made on” speech might be a good place to pursue these ideas. The play, certainly, asks us to think hard about the permeable lines between the real or “natural” & the constructed.

Given that I was hoping to jump ship from my current profession (publishing) into academia (sooner than later), this image immediately brings me to the state of affairs in regards to finding a position in English academia.

Needless to say, the distressed mariners represent the hundreds of hopeful applicants to the one position at Podunk State University, holding on for dear life to their reference letters, well-constructed cvs, and letters of intent.

I am cautious of offering my take on the representation of the minions, Ariel, or even Propero. I leave that to the individual’s imagination. 🙂

It may well be that the mariners are supplicants/applicants, but doesn’t that make the difference between the devilish spirits in the air and the somewhat distracted magus on shore interesting? If the spirits are the (admittedly brutal) job market, who is Prospero? That’s a question that needs answering, whether we want to keep playing with this allegory or not.

I’m still thinking this through, but one pedagogical/classroom reading would place the students’ (i.e., the sailors’) quest to grasp/understand knowledge (i.e., the sea) at the mercy of the instructor (i.e., Prospero). In that reading, I see the instructor as troubling their reading (i.e., whipping up the sea) by asking provocative questions about aspects of the text that might otherwise go unnoticed by relatively fresh readers.

This metaphor falls apart when I think about it terms of the god-like status that Prospero gives himself… When I taught high school, I was lucky if I could garner about 1/3 the academic authority of a scoutmaster, though that clearly says more about me than it does about teaching in general…

It helps to have spirits to command, but it’s worth remembering (esp in the context of this metaphor) that Prospero remains very anxious about his power throughout the play — he castigates Miranda in 1.2 to make sure she’s listening, threatens both Caliban & Ariel, dissolves his charm in Act 4, etc. The sort of authority that he has — theatrical authority, we might call it, remembering also that it’s the only sort of authority we really have in the classroom — seems to need pretty constant maintenance to keep going.

I notice most of the play between the teacher and student has been covered already, and I don’t wish to try to take away from what anyone has already said. I’ve given a lot of thought lately to writing, and the teaching of writing. As a writer and teacher, I find that many of us in this field view our audience or readers as some sort of static, generalized mass. We intend to enthrall them with our knowledge and spoken or written word. We invoke grand language in the hopes of doing so, hoping that our Ariel will do as we command, and our subjects will become enchanted. Through our books and our wands we cast a spell, confident we have honed our skill enough to secure a strong enough hold on them. Prospero succeeds, perhaps, yet in this picture, he seems but a small entity, a minute detail amongst the bigger picture. It is not only Prospero’s magic, but the reception and interpretation of said magic that allows it to do his will. Ariel takes it upon himself to act, much like the imagination and thought of our readers and students. We do not lord over them; though I think we all idealize them, make them more eager than they might be, attribute more ambition than they have. Just food for thought here. Something to consider as we plan our classes and prepare our writing for the grand audience.

I see that. I think it’s because of the concept of enchantment. You can never know when it will wear off, or if it will even work. Though we don’t treat our students how Prospero treats Miranda, Ariel, and Caliban, we are not so far away from a time when teachers did so regularly. We choose other methods to keep the spell active.

So all teachers are like Prospero following the masque, trying to cover for revels that have suddenly ended? That makes sense to me. We do have some ordinary institutional magic at our disposals, I suppose.

In looking at this picture as an allegory on English grad school education, (or education in general) my first thought is “conflict”. The conflict in an allegorical sense for me represents an idea of tension between unpractical knowledge (English grad school/academia/Prospero) vs. practical knowledge (non-academic lifestyle/business, industrial, or service job/ the sailors and politicians). As grad students, most of our thoughts and efforts apply to abstract ideas, concepts, and theories. These things don’t necessarily have a direct effect on a person’s everyday life. It seems that in academia, our work does not provide a tangible service to others. Unlike a sailor on a boat helping passengers get from point A to point B safely. The same can be said of pilots or train conductors, their work can directly influence the daily lives of other people, while also having an incredible responsibility to the well being of those on board. Prospero originally loses his position of Duke because he cannot reconcile his academic nature with the daily bureaucratic concerns of ruling a city. I’m sure many people who are not grad students may question the importance of studying literature and art in general. Not only in “The Tempest” but in society there is a disconnect between the academic and the non academic, i.e. the scholar alone in his ivory tower with his books. I think this picture may be an extreme response to those questioning academic pursuits. I am not suggesting we attempt to conjure up any natural disasters, but rather that Prospero hopes to stand up for himself through his mastery of non-material intelligence to prove his and it’s importance.

A nice post — but I wonder if the middle term of Ariel & the spirits might be usefully interposed between Prospero (the head-in-clouds academic) and the practical sailors? The play is quite clear that the magus himself doesn’t do the supernatural work; he just bosses the spirits around. “Use your authority,” as the Boatswain says in a slightly different context.

What I find interesting is the parallel I see between our interpretation of this image and the statements of teaching philosophy I’ve read/written for Harry Denny’s class. In both, the focus appears to be on the teacher/Prospero and what they control (Ariel, etc) instead of the students/mariners. They are painted similarly, the mariners, yet they have individual characteristics. We never focused much on them in our discussion, and the philosophies I’ve read treat the students as one entity, be it an eager to learn one, a group desiring only to express themselves, etc. The teacher/magician casts the spells and controls the entities, all to a certain purpose, one seemingly at times more important to the teacher than to the class itself. Teaching is about the students, even if The Tempest is not much about the mariners. Without either, however, our magic is useless.