In the hot days of mid-July, at long last I slipped into the phase of quarantine that includes re-reading Camus’s The Plague. Early on, when everything seemed new, I listened to an audio version of Boccaccio when I drove to DC to extract my son from his college dorm. In the confusion that followed , I skimmed Defoe, and turned through some fragments of Dekker’s Wonderfull Yeare. I indulged myself by blogging about Love in the Time of Cholera in late March.

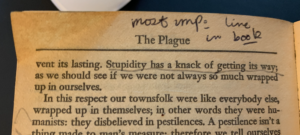

But until now I’ve been avoiding Camus. It’s a book I remember falling deeply into when I read it during my junior year of high school. I still have that 37-year old copy, slightly worn, with not always decipherable notes. Even then, I seem to have figured out that the “most imp. line in [the] book” came early: “Stupidity has a knack of getting its way” (36). Yes, it does.

[My teenage self in the ’80s surely could never have imagined that virtually any quotation of The Plague right now reads like a subtweet of the USA in 2020. Not that anyone knew what a subtweet was in 1983!]

Much of what I remember of the novel I found again, as lucid as before: Camus’s moral urgency, his compassion for a wide range of (mostly male, as I don’t think we discussed in class back then) characters, and his patient, slow unfurling of the progress of plague through the town of Oran. I remember the novel’s insistence on clear understanding as the key to moral living: “The soul of the murderer is blind, and there can be no true goodness nor true love without the utmost clear-sightedness” (124). A bit of a know-it-all as a teenager, I liked the idea of values built on knowledge.

But though the worship of “comprehension” and semi-scientific clarity remains, in particular via the doctor-hero Rieux, a second thread through the novel seems more striking to me now. The additional cardinal virtue besides individual knowledge is social obligation: “It’s a matter of common decency. That’s an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of fighting a plague is — common decency” (154). Or, as the narrator describes the sick city a bit later, “This business is everybody’s business” (194). The implications for America in 2020, divided against ourselves by the very leadership whose job is to unite us, seem too obvious to detail.

Living during our own plague-time now, I feel these two imperatives — to know, and to be decent — as rival twins. The urge to be clear-sighted has me, like many of us, swallowing down huge gulps of information: statistics, epidemiology, public health theories, and other technical fields in which I’m not competent to form a reliable opinion. But at the same time, behind the numbers that I scan daily from Florida, Texas, Arizona, California — a few months ago the numbers were from New York, Boston, New Haven, and before that Italy, Wuhan, Tehran — I feel an enormous urge toward compassion and decency, though I can’t always tell how to put those feelings into action. What does it mean to act decently toward someone who’s lost their parent, their business, their life’s work? How does decency interact with comprehension? Is wearing a mask an act of comprehension — because we know now how the virus spreads — or of decency — because it shows a collective care for our neighbors? Can everything be both of these things, always?

In re-reading The Plague I also remembered what seemed to teenage me, and to some extent still to old guy me, a central conflict in the novel, between the Jesuit Father Paneloux’s desperate faith in divine order and Dr. Rieux’s refusal to moralize. “Perhaps we should love what we cannot understand,” urges Paneloux, to which Rieux responds with his own articulation of absolute truth: “I shall refuse to love a scheme of things in which children are put to torture” (203). What seems most admirable to me now about Rieux is his modesty, his acceptance that he might not be able to find any “scheme” at all, once he casts off traditional structures such as the Church and the law. Decency might be better than any scheme.

There are a lot of figures in Camus’s novel who present mini-arguments for how to endure the pandemic: Grand the clerk and failed artist, Tarrou the intellectual, the journalist Rambert, the petty criminal Cottard, and others. I remember that I tried, back in ’83, to lay out a sort of “which one’s plan works best” reading of the novel. But this time through, I don’t know — there was something a bit schematic about each of the figures, even the most intellectually complex such as Tarrou and Rieux. Their stories are engaging, meaningful, diverting, varied. All the usual things a novelist makes us feel, we feel. But the core driving force of the novel isn’t human at all. “What’s natural is the microbe,” Camus emphasizes. “All the rest — health, integrity, purity (if you like) — is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter. The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention” (235-36). Another subtweet of 2020, this time not to governmental stupidity but instead a challenge to our own tired, almost-six months in spans of attention? How often does your attention lapse these days? How long can our attention stay sharp?

Who in Camus’s novel is that “good man,” who infects almost no one? The doctor interacts with his patients and even brings sick people into the apartment he shares with his mother. Tarrou volunteers to organize a sanitation crew whose work does not sound very “socially distant.” None of the citizens of Oran appears to be isolating as a matter of course, though one heart-wrenching scene divides a sick child from his family. (The child dies in the hospital with Rieux; the father, a magistrate, ends up wanting to volunteer at the isolation camp rather than return to his government job.) Crowds pile into church to hear Father Paneloux’s sermons, and a stranded-by-quarantine opera company even performs “Orpheus and Eurydice” to packed houses once a week. All the cafes are open. The pervading horror of 2020 — that we know how to “stop the spread,” and yet are failing as a collective body to do it — isn’t quite the sickness the novel describes.

I mostly agree with critics who say that it’s too simple to think of The Plague as an allegory for fascism, or even for the four-year suffering of France under Nazi occupation. But the mysterious fading away of the illness, which in the famous final words of the novel, may yet “rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city” (287), clearly has a political flavor. Perhaps, yet again, the jab is applicable to the USA in 2020 as well as Camus’s France in 1947? Vigilance, “attention,” and a clear eye for rats seem essential tools to maintain decency in the body politic.

One new discovery of the 2020 reading was a salt-water interlude. The moment comes just before Grand’s recovery marks the start of the city’s turn away from plague — and also shortly before the one-after-the-other deaths of Tarrou and Dr. Rieux’s wife conclusively isolate our hero. The two friends, Tarrou and Rieux, talk their way past the lockdown guards and go for a sea-swim by the empty pier. It’s an understated, faintly homoerotic, deeply resonant moment of physical escape: “For some minutes they swam side by side, with the same zest, in the same rhythm, isolated from the world, at last free of the town and of the plague” (239). In a novel with few consolations, except Grand’s unexplained recovery and the at-least-temporary withdrawal of the disease, the night-swim, which is almost the novel’s only moment outside the city walls, marks a dive away from infections and an imaginary engagement with another environment.

The water in Long Island Sound was too cold for me when corona-time started in March, but since late May I’ve been swimming every day. I follow the tide around its circuit, since it’s nicer here to swim within an hour of so of the high-water mark. Today the 9:35 am tide put me in the water around 10, in between a few rain squalls, loving the bouncy disjunction of being in slightly rough water. I sneak away each day into the grey-green flood, not so much to be apart from the pandemic, because of course I don’t forget the world when I swim, but because the act of immersion, of clogging my eyes and ears and nose to everything around me but salt water, works like a tiny meditative practice.

Today when I swam through choppy swells I was thinking with Rieux and Tarrou. About comprehension, and how hard it is to live up to that pitiless goal. And about decency, and how much I hope our world can find it again.