Who rules the world?

Stories about the violent birth of the Roman Empire are always allegories of authority — how to get it, how to use it, and at what cost does it come. That’s how I read Virgil and Ovid, not to mention Shakespeare’s Roman plays. That’s what I saw last night on the Upper West Side in the hours before today’s torrential rainstorm.

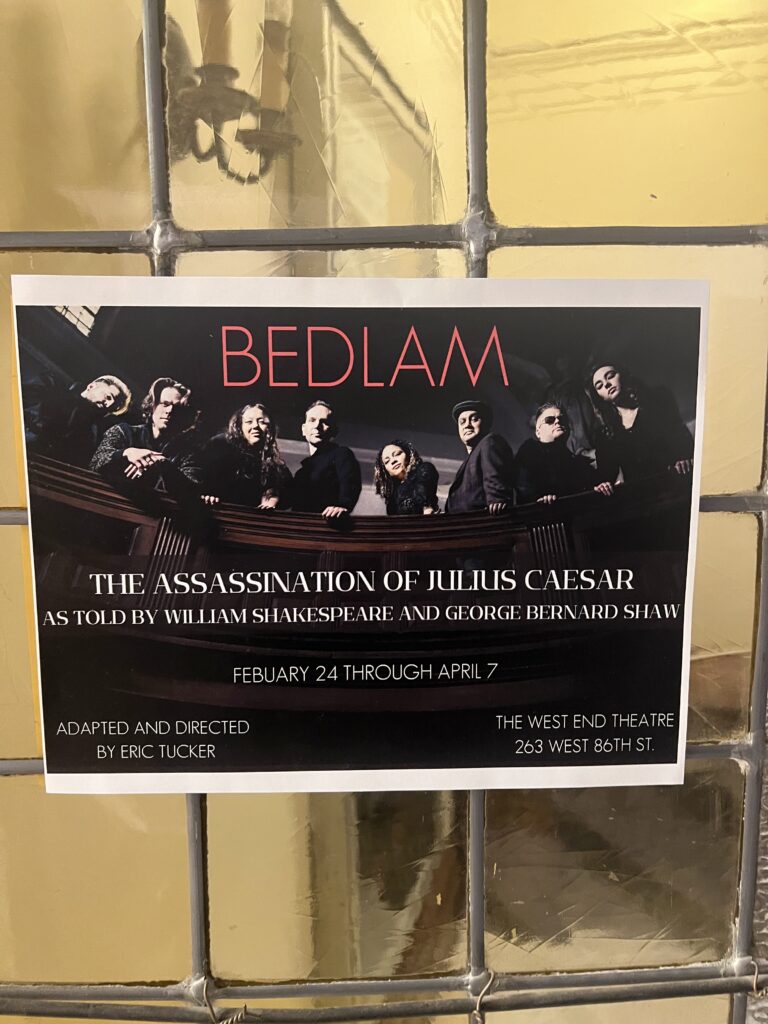

At the West End Theatre, a cozy space upstairs at the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew, I enjoyed a wonderfully triplicate rendition of this story. Courtesy of the brilliant experimental group Bedlam, this intense two hours without intermission mashed together Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, in which the nascent emperor gets murdered by his peers, with Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, an 1898 play that I’d not seen before that portrays a philosophical and somewhat bloodless Caesar’s earlier encounter with the Egyptian Queen. The third portrayal of authority, however, was the most powerful – the Director of the theater company, who controls all the actors all the time, interrupting speeches and extracting confessions. Who rules the world, really? (I might note here that Bedlam’s Eric Tucker gets credited as having “adapted, directed, and designed” the production.)

Juxtapositions were the heart of the show, and the cross-casting was brilliantly managed. Andrew Rothenberg played Caesar in both storylines as well as the Director, and he was wondrously imperious, bossy, and manipulative. He doled out the egotism of Shakespeare’s proto-emperor, who is happy to remind everyone that “always I am Caesar” (1.2.211). Rothenberg was equally strong playing the more philosophical and strategic vision of control, power, and impassivity that define Shaw’s superman. But there’s no real question that the Final Boss in the play was the Director. He pushed the excellent Rajesh Bose out of the role of Caesar to grab it for himself. (Bose shifted to the Egyptian God Ra, a semi-chorus in Shaw’s play, and acquited himself very well.) The Director bossed around the naive young Cleopatra as played by Shayvawn Webster, cross-cast as an idealistic Brutus. The Director interrupted Mackenzie Moyer as Portia in the middle of her moving speech about her love for Brutus (2.1) and decided on the spot to cut the scene. (The actors protested that it’s the only real moment for a woman character in Shakespeare’s play, which is true.) The Director required confessional moments from his actors, and then belittled them about what they revealed.

I was reminded a bit of the director / casting agent / Iago figure in Keith Hamilton Cobb’s American Moor, who sat among the (mostly white and at least middle-aged) audience when I saw the show at Cherry Lane in Manhattan just before the pandemic. Power comes from positioning, and from all those structures that surround us.

Unlike in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, which in a stroke of fortune I’m going to see on Monday night from the Red Bull Theater, Caesar and Cleopatra didn’t face each other down as competing principles of power in this play. Rather, Shaw’s Caesar educated Cleopatra in the practice of power, teaching her to out-maneuver her brother and rival Ptolemy while Caesar himself defeated his Roman rival Pompey, a mask of whose pickled head in a jar makes a lively appearance in the show, including some time on an audience member’s lap. Shakespeare’s Brutus showed his political naivete, which is exactly what Shaw’s Cleopatra may be learning to outgrow. The double casting provided an interesting take on these two characters, though it also somewhat muted the moral dimensions of Brutus’s struggle.

One of the liveliest figures of the night was Bedlam regular Labod, who played a physical and effusive Cassius as well as Cleopatra’s wonderfully-named Egyptian servant Ftatateeta. (The Director makes fun of this character’s name, of course). Labod’s intensity as Cassius somewhat overwhelmed Volino-Gyetsa’s physically smaller Brutus – but their late scene together fighting and reconciling (4.4) was nicely paced. Stephen Michael Spencer made his Bedlam debut as Mark Antony and Rufio, Caesar’s military aide in the Shaw play. He chewed the scenery into paste in the funeral oration, which was nicely set up. The play opened with Caesar’s dead body already on the floor, with the conspirators getting meta-theatrical – “How many ages hence / Shall this our lofty scene…” 3.1). Spencer’s Antony started to get warmed up in his speech, and just then the Director interrupted to shift the scene to Egypt (and the Shaw play). We finally got back to that speech almost two hours later. But it was worth the wait!

Update: Before I forget I wanted to note the goofiest directoral move of the night, in which the case plays all of 2.2 – the back and forth on whether Caesar will or won’t go to the Forum, including a nice bit of manipulation of the big man’s ego by conspirator Decius Brutus – in over-the-top mafiosi accents, part The Godfather and part The Sopranos. Italians in the New Jersey waste management industry, Italians during the last days of the Roman Republic – the gag seems to have been irresistible. And lots of fun!

Maybe I just have trouble sitting for over two hours, but I might have pulled the curtain at the end of that speech when it came around again, when the lights went out and Mark Antony in darkness intoned “MIschief, thou art afoot” (3.2). But I understand that they wanted to shoehorn in the brutal death of Cinna the Poet, and Portia’s suicide, and the fight between Brutus and Cassius in act 4. The final scene of the night returned to the meta-plot of the Director, whose actors may be just about to rebel. “Go fuck yourself,” muttered Labod, no longer in character as Cassius or Ftatateeta, on his way offstage. Everyone was outraged at his brutality and cold-bloodedness. They were ready to break into open revolt –

But then the curtain closed, and the Director’s job was done, his power secure, for another night.